|

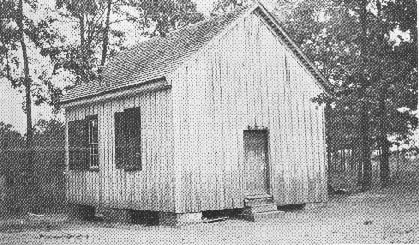

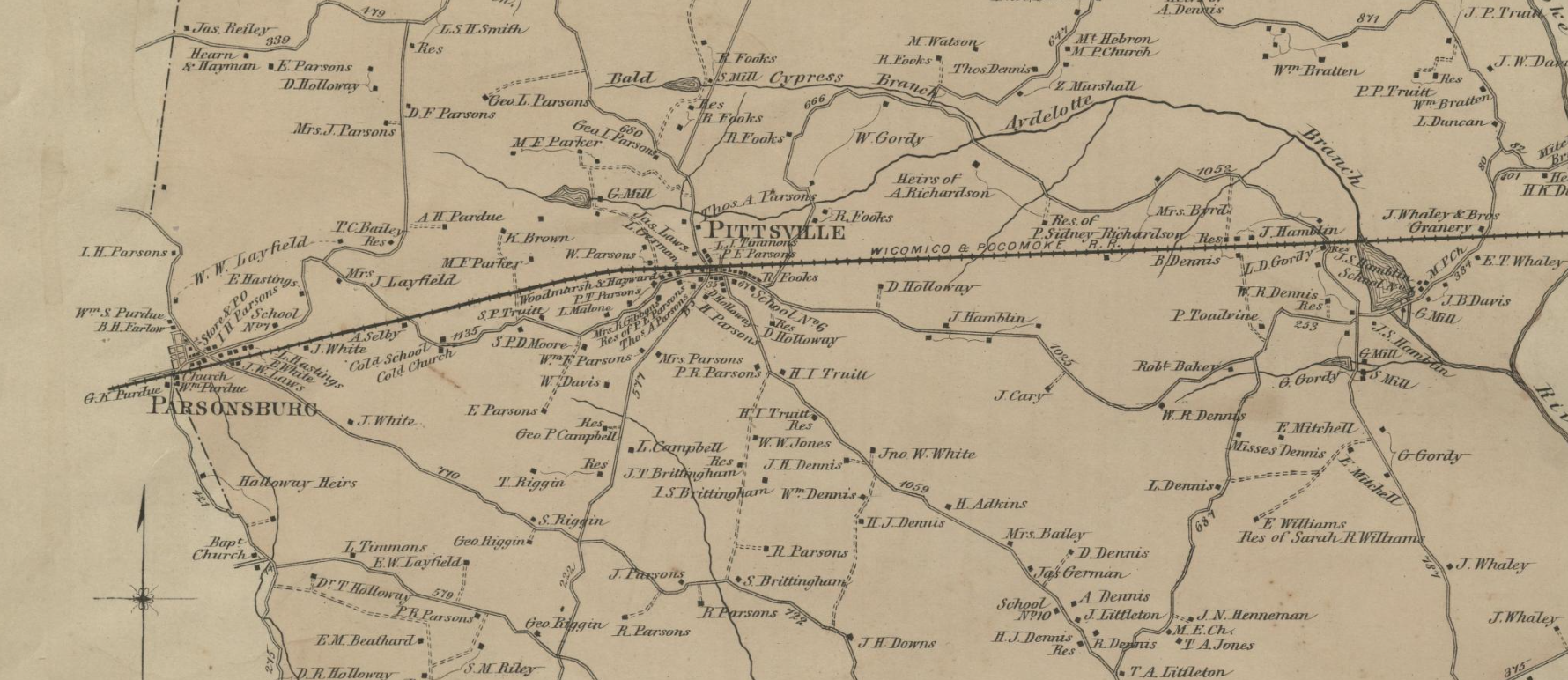

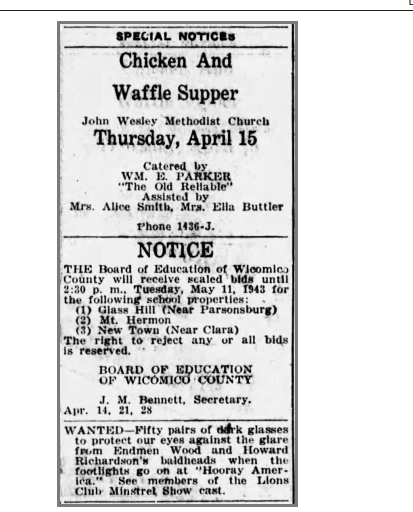

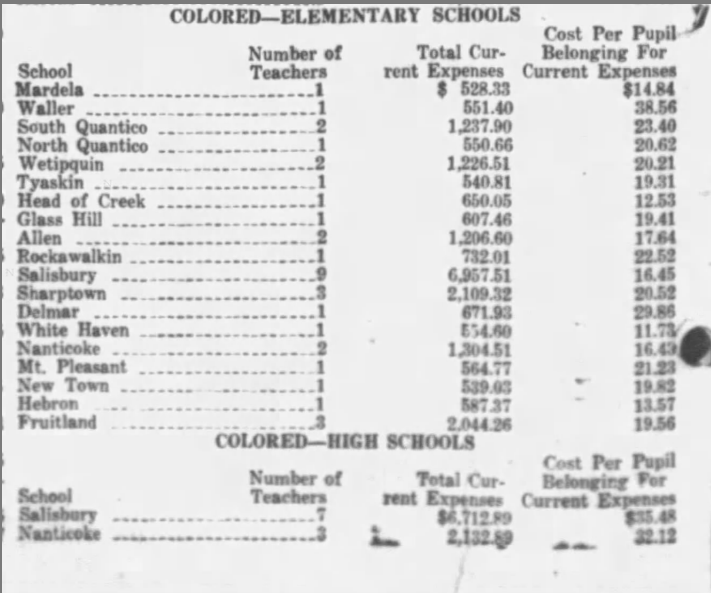

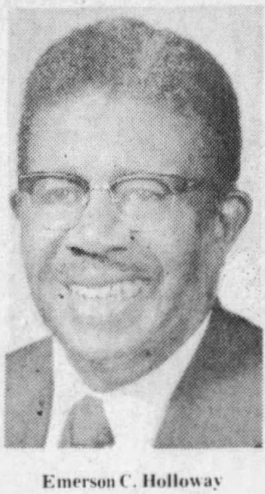

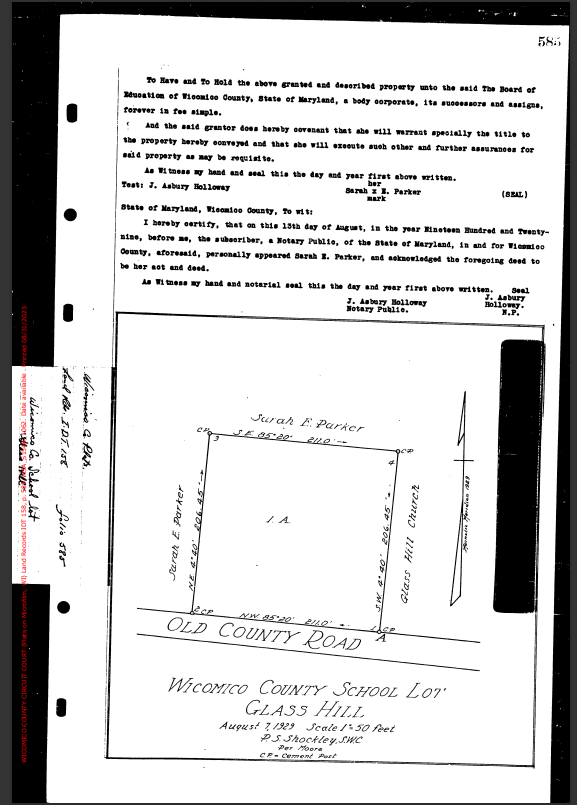

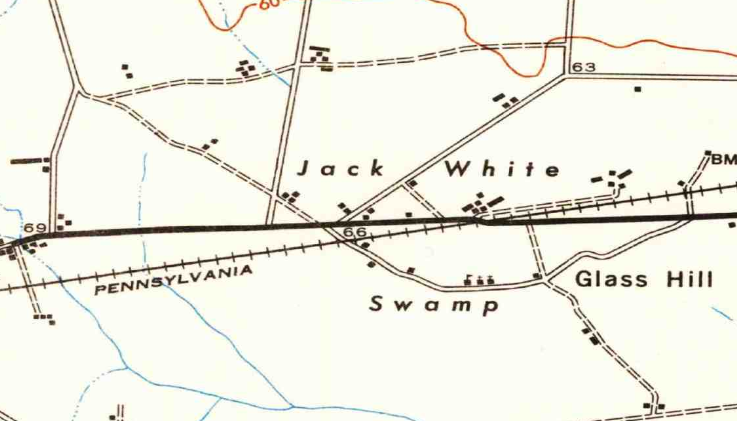

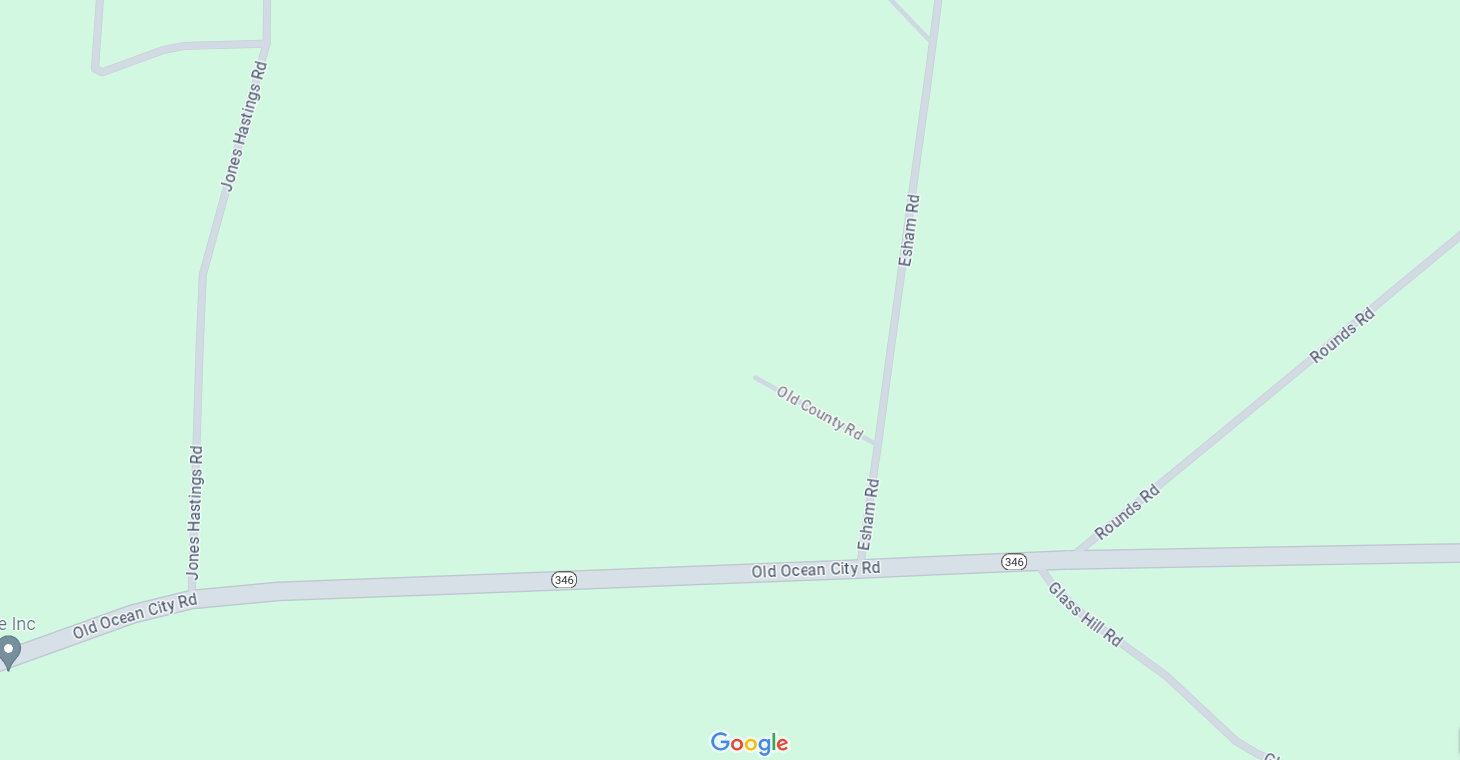

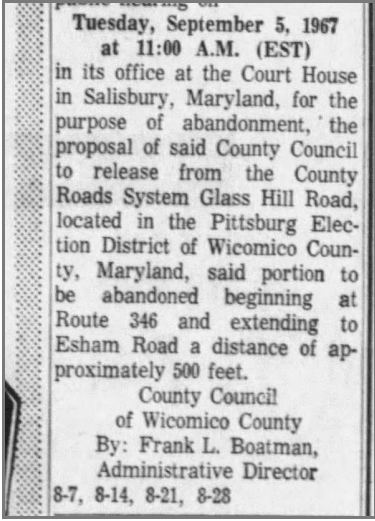

Article by Andre Nieto Jaime Glass Hill, nestled between Pittsville and Parsonsburg, was once a thriving Black community with a history that dates possibly to the late 18th century. Within this historic neighborhood once sat a one room schoolhouse, first built in the 1870s, that provided an education to the Black school children within the surrounding area. This early education was vital in the period following the abolition of slavery. At a time where opportunities for education for Black students were limited due to institutionalized biases, lack of resources, and the fact that the formerly enslaved now had to navigate their newly acquired freedom with little guidance, these early schoolhouses were crucial. These schoolhouses also had other important functions, often serving as community centers, and helped foster unity within African American communities. Glass Hill School performed its duties as an educational and community hub for at least 70 years before being closed down around the mid-20th century. Old Photograph of the Glass Hill School in Glass Hill Delmarva African American History Unknown Date Glass Hill School was just one of the many single room Black schoolhouses to crop up after the Civil War. As mentioned in the introductory article about Glass Hill, the school was built sometime in the 1870s across from the Bishop Methodist Church on Glass Hill Road. Both the church and school appeared across from each other on the 1877 Atlas of Wicomico, Somerset & Worcester Counties as “Cold [Colored] Church” and “Cold [Colored] School” in the Pittsburg District Map, confirming that the school must have been built sometime in the early 1870s. 1877 Atlas of Somerset, Wicomico, and Worcester Counties Pittsburg District Internet Archive 1877 The school appeared to have been operating well into the 20th century, with some newspapers claiming that activist Dr. Maulana Karenga (birth name Ronald Everett) attended this very school in his childhood, which would have been in the mid to late 1940s. References to the school in newspapers begin appearing consistently in the 1920s. Most of these come from The Daily Times, which published a handful of articles that mentioned Glass Hill and the school. At the time, nothing out of the ordinary would have stood out about these papers as they describe rather mundane day to day happenings and details such school reports, news, teacher rosters, and other aspects of schools. However, these old newspapers disclose several details relating to the schoolhouse. First, these papers hint at the period in which the school was active. While the 1877 Atlas has revealed that the school existed by at least 1877, the time when the school closed is a little more obscure. The Maryland Historical Trust’s inventory form WI-496 makes no mention of when the school ceased to operate. The hint provided in this document is that the building was moved to Pittsville and restored in the 1980s, meaning that the schoolhouse was in its original location for over a century. However, the school ceased its operation before this relocation and restoration. References to the school in newspapers began to decline by the 1940s. One of the last mentions of the school in its active years was an update to the roster of teachers in 1941, owing to several male teachers leaving to serve in the army. Two years later, another article stated that the Wicomico Board of Education was receiving bids for three school properties, one of which was Glass Hill. This most likely was the single room school’s lot, but it is also possible that this was a lot that was purchased by the Wicomico Board of Education in 1929. Either way, the age of the school, its one room structure, and the beginnings of integration after Brown V. Board of Education in 1954 almost certainly rendered Glass Hill School obsolete by the 1950s. By 1969, the school was being referred to as “the former Glass Hill School,” seemingly confirming its closure sometime in the 1940s or 50s. Notice Newspapers.com, The Daily Times April 14, 1943 Another element of Glass Hill, and segregated schools in general, that these newspapers reveal is how underfunded Black schools were. For example, the 1934 summary of school expenses shows that many White single teacher schools’ expenses were nearly double that of Black single teacher schools. Glass Hill’s total expenditure in this report was $607.46 while the expenses per pupil was $19.41. Meanwhile, the total expenditures of the single teacher White schools were all over $1,000 with expenses per pupil ranging from $29.49 to $54.13. Even when compared to Rosenwald Schools, which were relatively newer, but still often only had one to three teachers, had expenditures higher than these older single room schools. Sharptown School’s (San Domingo School) total expenditure was listed as $2,109.32 while South Quantico’s was $1,237.90. Yet, despite the funding disparities and older construction of the building in comparison to the other schools of Wicomico County, Glass Hill School continued providing early education for Black youth in the Pittsville-Parsonsburg area of Wicomico County well into the 20th century, a testament to the resourcefulness and strong will of the Glass Hill community. Annual Report of the Public Schools of Wicomico County Newspapers.com, The Daily Times November 20, 1934 These articles from the 20th century also reflect the impact that Glass Hill School had on an individual level. Two publications from The Daily Times described how Glass Hill School provided an education for Willie Allie Birckhead from Pittsville and another individual, Clifton Alton Trader, from Parsonsburg in their obituaries. Had the school not existed, these two students as well as the others in the area would have had to travel a much farther distance to the next closest school, likely Delmar. However, considering the distance and the fact that these children were needed nearby to work on family farms, they likely would not have received any formal education apart from any nearby tutors. W. Allie Birckhead Newspapers.com, The Daily Times November 9, 2003 Glass Hill School not only offered opportunities for local students, but to educators as well by becoming a place where several teachers started their careers. Miss Dixie Kier began teaching at Glass Hill in 1917 and taught there for three years before moving on to Delmar and Salisbury. Her career lasted 43 years, with Kier retiring in 1958 and picking up work at a Sunday and Bible school. Likewise, Emerson C. Holloway, lauded as being Wicomico County’s first male teacher, began his 37 year long career at Glass Hill School. Here, he became fondly remembered by the community, evidenced by an anecdote given by a parent, Mrs. Esther Parker Wilson. In 1939 Holloway organized a Christmas performance in which every child pitched in to create decorations or other preparations. The performance itself involved school children describing what they wanted for Christmas, singing Christmas songs, and recreating the Nativity. Wilson, among other parents, was so moved by the celebration that she said that Christmas “was never rivaled by another in that school," showing that Holloway truly had an immense impact not only on the children at Glass Hill, but the community as well. By the end of his career as an educator, Holloway had become the vice-principal at West Side Intermediate School, retiring after becoming the first Black man elected to the County Council. Thus, little Glass Hill School, provided these educators a place to gain experience and start off their lengthy careers of sharing their knowledge with countless school children across the county. Emerson C. Holloway Newspapers.com, The Daily Times November 15, 1978 This old schoolhouse also provided services to the surrounding community by serving as the Seventh Tabernacle’s early home when the congregation first came to Glass Hill. This religious organization was founded by John Elzey Parker when he came to visit his sister, Jennie Parker, in 1921. After the visit, J.E. Parker decided to settle in Glass Hill, organizing the Seventh Tabernacle, and began using Glass Hill School alongside neighboring houses to hold their meetings until they secured a more permanent location in Salisbury where they remain to this day. Even Willie Allie Birckhead, the student from Pittsville, became a member of the Seventh Tabernacle. Seventh Tabernacle on Seminole Boulevard in Salisbury Delmarva African American History c. 2011 Glass Hill School continued to serve its community well into the 20th century. However, by the early 20th century, the Rosenwald School Building Program (which was discussed more extensively in a previous StoryWay) had begun its mission of building schoolhouses for Black school children throughout the South in underserved communities. These schoolhouses were by no means state of the art, but they did help supplement and replace many of the old schoolhouses that were aged, underfunded, and falling into disrepair. They boasted a larger size and while they were still, in most cases, single roomed, they could often be partitioned into separate rooms for different grades. This allowed for increased student capacity, more teachers, and for more flexibility when it came to the usage of space. One of these schools was set to be built in Parsonsburg and was budgeted in 1929-1930 during the last big wave of school building by the Rosenwald Fund. The mention of a Rosenwald School being budgeted in 1929/1930 lines up with a transaction and land survey conducted in August of 1929, where Sarah E. Parker turned over 1 acre of land on Old County Road to the Wicomico Board of Education. This record is named “Wicomico County School Lot Glass Hill” suggesting that this lot was meant to be used for the construction of the Glass Hill Rosenwald School that was budgeted around the same time. A newspaper publication also describes this exchange, noting that the Board of Education of Wicomico obtained one acre in the Pittsburg District for the consideration of $10 from Sarah Parker. Preparations were seemingly being made to begin construction of a new school in Glass Hill, yet there are few, if any, references to a Rosenwald School in Glass Hill beyond these few documents. Wicomico County School Lot Glass Hill Wicomico County Circuit Court Plats Microfilm 1929 Today, Old County Road in Parsonsburg is a dead end and barely extends off Esham Road. However, in the past it connected to Jones Hastings Road, suggesting that a new schoolhouse may have been built somewhere on this road, but then demolished when the road was abandoned and repurposed for farmland. Looking at a map from 1950 shows Old County Road heading west and connecting to Jones Hastings Road with two structures half way down the road on its north side. To the east, the road goes through Esham Road and Route 346 (Old Ocean City Road) where it connects to Glass Hill Road on the opposite side and cuts through the railway that no longer exists. Looking at a map today (Google Maps for example) shows that the western stretch of Old County Road now terminates in trees and farmland occupies where it once was. Its eastern half section no longer connects to Glass Hill Road, simply intersecting with and ending at Esham Road now. Pittsville (1950) U.S. Geological Survey c.1950 Glass Hill Google Maps 2024 This eastern truncation can be explained by a newspaper publication from 1967 in which a public notice is given about the proposal to abandon a section of road in the Pittsburg district. This section of road is described as “beginning at Route 346 and extending to Esham Road a distance of approximately 500 feet,” which lines up with the small stretch of Old County Road that cut through Esham Road and Route 346 into Glass Hill Road. Considering this section no longer exists, it seems the proposal was accepted. At some point, the western part of Old County Road must have been abandoned in a similar manner and repurposed as farmland. Public Notice The Daily Times, Newspapers.com August 7, 1967 Another explanation for this Rosenwald School is that it never got built due to economic factors, namely the Great Depression. This economic upheaval may have gotten in the way of funding. The Rosenwald Fund found itself struggling to make payments in the 1930s and entered a decline. The State of Maryland and the Wicomico Board of Education also would have also struggled to put funding into building a new school and, like the Rosenwald Fund after 1931, likely preferred to maintain existing schools for the time being. Glass Hill residents also likely struggled to match the fund, with many leaving the area to look for employment elsewhere. A smaller community also could have meant that they did not see a need for a new Rosenwald School anymore and scrapped the idea all together. Finally, there is also the possibility that the school was built, and it just does not exist anymore. However, this seems unlikely as there are barely any references to anything other than the small schoolhouse in newspapers and documents in government databases. It is more likely that the school was simply never completed due to economic issues and the Rosenwald Fund deciding to end their school building program in 1932. Whatever the fate of this Rosenwald School was, the fact remains that the 1870s Glass Hill School managed to provide a vital education for children in the rural Parsonsburg area for around 70 years. Had the school not existed, school children would have had to travel much farther or even moved to different towns with extended family to go to the nearest African American school assuming their families could afford the loss of an extra set of hands at home. According to census records from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many of these Black families’ occupations were farmers and homemakers; a lifestyle that relied on having every family member at home being involved in farm duties to be successful. While Glass Hill was a small school operating on a relatively small budget, it had a lasting impact on the community by giving Black school children greater access to education than their forefathers, a chance at social mobility through literacy, exposure to ideas such as equality, and by serving as a community hub alongside the Bishop Methodist Church. References: Primary: “Answer to Today’s A Moment in Time.” The Daily Times, February 9, 1998. “Annual Report of the Public Schools of Wicomico County.” The Daily Times, November 20, 1934. Atlas of Wicomico, Somerset & Worcester Cos., Md. Philadelphia: Lake, Griffing & Stevenson, 1877. “Building Shore History.” The Daily Times, March 27, 2004. “Deeds Recorded.” The Daily Times, August 16, 1929. Google. “Glass Hill.” Google Maps. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://maps.app.goo.gl/ezM7zUzBANe4J75z5. “Holloway Plans to Leave Post.” The Daily Times, November 15, 1978. “Miss Dixie Kier.” The Daily Times, July 10, 1969. “New Teachers Are Appointed for Wicomico: Two Replace Men Now Serving in the U.S. Army.” The Daily Times, August 21, 1941. “Notice.” The Daily Times, April 14, 1943. Pittsville 1950. Sheet 5960 IV NW A.M.S. Series V833 U.S. Geological Survey. U.S. Geological Survey, Washington D.C. https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/ht-bin/tv_browse.pl?id=9560f698eb5fa32f5da2a4785097ccb3 “Public Notice.” The Daily Times, August 7, 1967. "United States Census, 1880." Entry for Isaac Smith and Martha E. Smith, 1880. FamilySearch, Annapolis, MD. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN79-GH Wicomico Co. School Lot Glass Hill. Land Records IDT 158, p. 585 MSA S1548-1062, Wicomico County Circuit Court, Salisbury, MD. https://plats.msa.maryland.gov/pages/unit.aspx?cid=WI&qualifier=S&series=1548&unit=1062&page=adv1&id=1393454667. WI-503 Calvary M. E. Church Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-503, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-503.pdf. WI-496 Glass Hill School Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-503, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-496.pdf. Secondary Sources:

Ascoli, Peter M. Julius Rosenwald: The Man Who Built Sears, Roebuck and Advanced the Cause of Black Education in the American South. Bloomington: Indianna University Press, 2006. Brooker, Russell G. “The Education Of Black Children In The Jim Crow South.” America’s Black Holocaust Museum. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://www.abhmuseum.org/education-for-blacks-in-the-jim-crow-south/’ “Clifton Alton Trader,” The Daily Times, January 19, 2003. Duyer, Linda. “Wicomico County’s Seventh Tabernacle.” Delmarva African American History. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://aahistorydelmarva.wordpress.com/2013/10/03/wicomico-countys-seventh-tabernacle/. Morris, Emily C., et.al. (eds). Recollections: Wicomico's One-Room Schools. Wicomico County Retired Teachers Association, 1977. National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form “Rosenwald Schools of Maryland.” Maryland’s National Register Properties, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/nr/NRMPSDetail.aspx?MPSId=25. “Remembering the One-Room Schoolhouse.” Shoreline, September 9, 2008. “Seeing Through Time in Glass Hill.” The Daily Times, May 14, 1996. “W. Allie Birckhead.” The Daily Times, November 9, 2003.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed