|

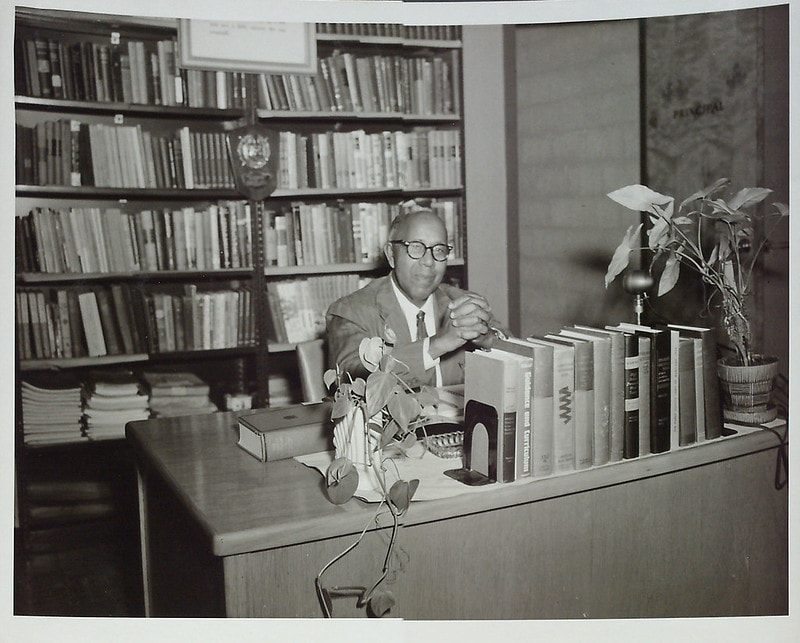

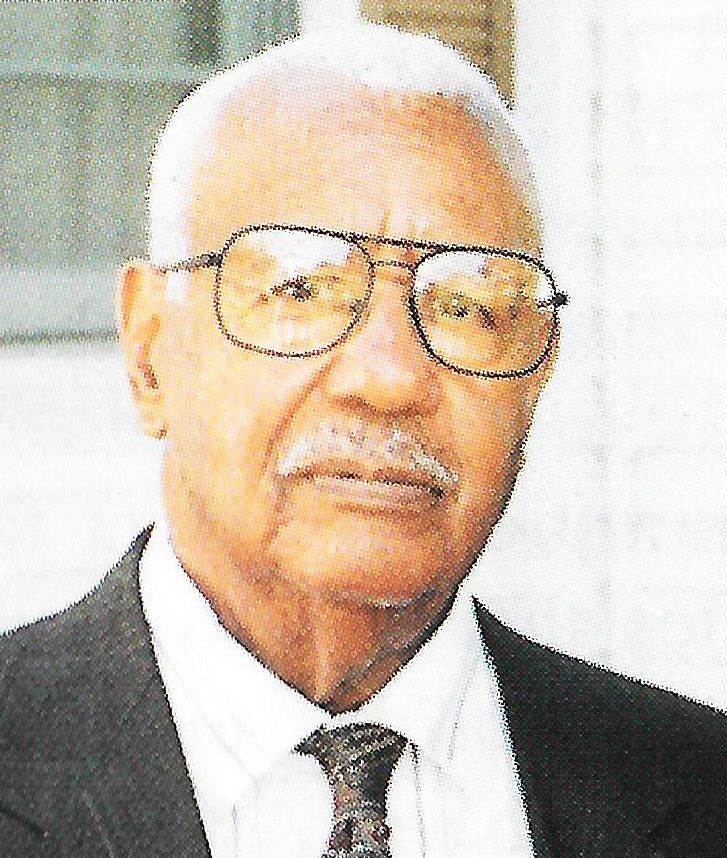

Dr. Clara L. Small Charles Chipman Headshot Undated Nabb Research Center Linda Duyer African-American History Collection (2012.021) Until recently, education for African-Americans on the Eastern Shore of Maryland and the Delmarva Peninsula had always been a bit precarious because it was dependent upon those in control of the power structure and of funding. During the colonial and antebellum eras, it was against the law to teach slaves to read and to write. The laws also extended to free blacks; the Maryland Legislature also passed punitive laws to punish anyone, black or white, who attempted to teach blacks. However, upon the issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation by President Abraham Lincoln, even though it did not apply to the State of Maryland, the desire for an opportunity to learn to read and to write became one of the most cherished freedoms for all blacks, regardless of age, sex, or previous condition of servitude. The desire for even the mere rudiments of an education was planted during the reconstruction period. Despite the scanty, unequal funding and the dilapidated structures, the lack of text books and supplies, unequal salaries for the few qualified teachers that were willing to teach in the area, education for African Americans was initiated. The burning of churches which served as the earliest schools and the threat of death to the persons of those who attempted to assist in the new educational process was always apparent. However, those threats did not deter attempts to educate Blacks. The establishment of Rosenwald Schools, such as the Germantown School in Berlin and the San Domingo School in San Domingo/Mardela, as well as the Sturgis One-Room Schoolhouse are examples of successful attempts at education. Locally, some individuals, such as Stephen Long from Pocomoke City, tried to satisfy the desire for an education in others and paid the supreme sacrifice of losing his life, simply because he encouraged young black boys to get an education. Fortunately, educators such as Charles Chipman, Kermit Cottman and Oscar J. Chapman continued in the footsteps of the late Stephen Long. Professor Charles Chipman (1888-1987), a native of Cold Springs, New Jersey, just outside of Cape May, came to Salisbury in 1915. Mr. Chipman had previously been offered a position at Tuskegee Institute but upon the death of Booker T. Washington, chose to come to Salisbury instead. He came to Salisbury as the Supervising Principal of the Industrial High School which later became known as Salisbury High School in 1930. He arrived in Salisbury to find that the school was a rented structure and in desperate need of repair, so his first task was to convince the Wicomico County Board of Education of the need for a new building with adequate facilities to suit the needs of the students, faculty and community. The condition of the school was appalling to Professor Chipman because he had received a superior education in Cape May, New Jersey and had graduated from Howard University in Washington, D.C., which was unusual for a black person in 1915. The Wicomico County Board of Education allocated approximately half of the necessary funds to construct the new school. To raise the remainder of the funds, Professor Chipman organized a community committee to complete the funding for the other half of the proposed building. The proposed building was designed to have 25 to 30 rooms and an auditorium. Unfortunately, the cost of materials increased, so the money allocated by the Board of Education proved to be insufficient to complete the building despite the matching funds raised by the community committee, so more funds had to be raised by the community committee, but it was finally completed. The completion of the building did not signal the end of Professor Chipman’s woes. He also had to find funds for the furnishings of the school, books, supplies, and other materials that were necessary to keep the school running adequately. Certified teachers who were willing to come to the Eastern Shore were also necessary. However, his greatest gift was to inspire his students to excel academically. Despite their meager resources, his desire for his students was for them to have morals and good character. As a result of his courageous attempts to provide for the educational needs of his students and to provide an outlet for their social needs as well as to prepare them for a life beyond Salisbury and Salisbury High School, Professor Chipman earned the respect of his students and the community. Charles Chipman at His Desk Undated Nabb Research Center Linda Duyer African-American History Collection (2012.021) Salisbury High School Graduation Class Undated Nabb Research Center Linda Duyer African-American History Collection (2012.021) Professor Chipman’s influence was felt beyond Salisbury High School as he served on many boards, councils, and commissions. One noteworthy commission was the Salisbury-Wicomico County Commission on Interracial Problems or the Bi-Racial Commission. Professor Chipman and Dr. Elmer A. Purnell, the black members of the Commission, met with leaders of the Cambridge demonstrations and worked with Salisbury community leaders to avert riots in Salisbury that had plagued other communities. Chipman, Purnell, Attorney Hamilton Fox and other members of the Commission negotiated with and successfully opened public accommodations to all people regardless of race. In this way, educational and economic opportunities were provided for all people, training programs were established, and together, the Committee worked to minimize slum conditions and other problems in the county. Chipman helped to preserve the Salisbury John Wesley Church, the structure that was to become Wesley Temple United Methodist Church by purchasing it and then deeding it to the trustees of the church. Built in 1838, the structure was the oldest remaining African-American church on the Delmarva Peninsula and is now known as the Charles H. Chipman Cultural Center and serves as a community arts cultural center and museum. Chipman Elementary School on Lake Street is also named in his honor. Professor Chipman’s life is a testament to his attempts to improve the lives of his students, the community and all of the Eastern Shore. In short, he was a champion of all people. The Front Exterior of the Chipman Center, sideview 1990s Nabb Research Center Linda Duyer African-American History Collection (2012.021) Charles H. Chipman Cultural Center Similar to Professor Chipman, another educator, Dr. Kermit Atlee Cottman (September 6, 1910- April 3, 2007), gave his time and energy to educate the residents of the Eastern Shore. Born in Quantico, Maryland, to humble parents, Kermit Cottman became an educator and Supervisor of Public Schools in Somerset County for over forty years. As a youth, he became accustomed to adversity because of blatant racism and discrimination. From his youth he had been told of his great grandfather being taken to Princess Anne and sold by his master on the slave auction block where Metropolitan Church now stands. However, knowledge of slave ancestry did not deter him from desiring to succeed and acquiring an education even though there were no schools in close proximity to his home which was located between Hebron and Quantico. At the age of ten, Kermit and several Cottman family members learned that A.I. DuPont had begun to build schools similar to the Rosenwald Schools and that one of those schools, the Paul Laurence Dunbar School, had been built in Laurel, Delaware. The Cottmans made the decision to move to Laurel and to send Kermit to school in Laurel in order for Kermit and his siblings to receive an adequate education. At Laurel, Kermit excelled but there was no 12th grade, so he was sent to Delaware State College to complete his secondary education. He stayed there only two days, and transferred to Howard High School in Wilmington in an attempt to achieve his goal. Unfortunately, he remained there only a week because he became ill which required surgery and he lost a whole year of school. During that same year, Salisbury High School was opened, and once he recuperated from the surgery he walked from Laurel to Salisbury to attend school, a total of sixteen miles each way. Someone would offer him a ride, but he often caught a ride to Salisbury on the back of a Perdue truck because he could not ride in the cab of the Perdue truck, supposedly for insurance purposes. When he began to attend school in Salisbury, Professor Chipman learned of Cottmsn’s determination to achieve his goal, he offered him the opportunity to live at his home throughout the week. He respected Professor Chipman and was in awe of him, so he declined the offer and lived instead with his father’s relatives, the Howard Cornishes. During that trying year, Kermit’s father was disabled and Kermit wanted to quit school in order to help the family. However, his family would not allow him to do so. He graduated from Salisbury High School and was encouraged by Professor Chipman to attend Hampton Institute because he recognized Cottman’s potential. Professor Chipman began to personally prepare Kermit for Hampton Institute by making Kermit familiar with the ideals, beliefs and required readings that were so much a part of the discipline at Hampton. Kermit was accepted at Hampton Institute, and upon his arrival on campus was assigned to work in the cafeteria because he was so skinny. During the summers, he worked at the Hastings Hotel in Ocean City in order to obtain money to help defray his college tuition. While at Hampton Institute, Kermit had the opportunity to meet and converse with many outstanding leaders, such as Mary McLeod Bethune. He graduated from Hampton on June 2, 1936 and although he received numerous offers for jobs, he found that some of them had already been filled. One of those offers was to work at Lincoln High School in Frederick, Maryland to coach sports, even though his degree was in Social Studies. He accepted the job and due to his motivation and a good team, his team won the Maryland State (for Negroes) 1937-1938 basketball championship. While at Lincoln High School, in Frederick, Maryland, Kermit Cottman worked on a racial commission with Thurgood Marshall who later became the first African American United States Supreme Court Justice advocating higher salaries for African American teachers in Frederick. Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston had begun the fight to equalize teacher salaries and due to Kermit’s team winning the championship, as well as the recognition of his knowledge and skills in working with students, Kermit was offered numerous other positions. Among the positions he was offered were in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, Towson, Maryland, and Richmond, Virginia. Instead of accepting one of those positions, he chose to return to his home, the Eastern Shore, in order to help the youth of the area and the community he so dearly loved. Another reason he chose to return to the Shore was that salaries had been equalized for black and white teachers as a result of the lawsuit won by Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston. In 1939 Kermit Cottman’s career as a school administrator began when he was named Principal of the Somerset County Greenwood Elementary School and High School in Princess Anne. On January 1, 1947 he became the first African American Supervisor of Colored Schools. Once he became supervisor he forged a bond between the parents of Somerset County, the school and the Board of Education, and African American children in Somerset County began making scores equal to or better than African American children on the Western Shore. He remained in that position until the schools were integrated in 1969. From 1969 to 1978, he served as Somerset County Supervisor of Secondary Schools, but in order to continue in that position he had to also continue his studies. In 1947 he earned a Masters of Arts degree in Education at Temple University. He also studied at Columbia University and the University of Pennsylvania. In 1990, the University of Maryland awarded him an honorary Doctor of Laws degree. Kermit Cottman was Somerset County’s last Supervisor of Colored Schools. In short, he was a life-long learner and he encouraged others to do the same. During his 31-year career as a top administrator in Somerset County Public Schools, he served on many panels, councils, state boards and commissions, including the Webb Commission which studied the future relationship between Salisbury University and the University of Maryland Eastern Shore. His memberships, community concerns and appointments included the following: appointed by Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew to the State Advisory Council on Vocational and Technical Education; Regional Chairmanship of the Maintaining Active Citizens (MAC) of Dorchester, Somerset, Wicomico, and Worcester Counties; Chairmanship of the Somerset County Health Planning Committee; the UMES Chancellor’s Advisory Committee: the Local Vocational Advisory Council for the Somerset County Board of Education; the AARP Maryland Legislative Committee; the Planning Committee at Peninsula Regional Medical Center and many others. In each instance, Dr. Cottman’s goal was to teach and to enrich the lives of the students of Somerset County and of the region and to make life socially, economically and politically bearable for everyone. Dr. Kermit Atlee Cottman Undated Find a Grave Memorial People Outside of Hampton Institute Undated Nabb Research Center Linda Duyer African-American Historical Collection (2012.021) Similar to Professor Chipman and Dr. Cottman, Dr. Oscar J. Chapman ( -1994), also a native of the Eastern Shore, devoted his life to education on all levels and to serving the needs of the community. Born in Stockton, Maryland, Dr. Chapman endured the same hardships as Dr. Cottman as he too attempted to acquire the rudiments of an education. The only high school in the area that was available to him was Salisbury High School which was constructed during the principalship of Professor Chipman. Therefore, the only option for Oscar Chapman and others was to travel to Salisbury on a daily basis or to live with a family in Salisbury in order to graduate from high school. Fortunately, there were local educators with meager resources, but they had the desire to prepare black children for any possibilities, so they shared their homes throughout the week with black children eager to learn. Oscar J. Chapman’s fate was a bit different than most of his peers in Worcester County because his father had served for many years as a trustee of the public schools. After attending the community schools for seven years, he enrolled at Hampton Institute, in Hampton, Virginia, and completed his secondary education. In 1932, he received a Bachelor of Arts degree in English from Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, and began teaching high school in Denton, Maryland. The desire for an education was deeply embedded in his blood and in 1936 he received his Master of Arts degree in education and psychology from the University of Michigan, and in 1940 received the Ph.D. from Ohio State University. In 1940, he was named Professor and Chairman of the Department of Education at Arkansas AT&N College at Pine Bluff, Arkansas; served in the same capacity at N.C. State Teachers College, Elizabeth City State University (N.C.), Langston College in Oklahoma, and Tennessee A&T State University at Nashville, and as Professor of Education at Morgan State University in Baltimore, Maryland. In 1949 he moved into administration when he was named President of Delaware State College (now Delaware State University), until he was recalled to active duty as a Reserve Officer in the U.S. Air Force in 1951 during the Korean War. Even though he was an officer he did not neglect his educational background. He was assigned and responsible for the research programs at three bases located in New York, Illinois, and Colorado. In 1957, after five years as an officer in the Air Force, Chapman was officially released from active duty with the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. His immediate response was to return to higher education in order to help im-prove the lives of others. From 1957 to 1973 he served as Academic Dean and Chairman of the Graduate Council at Lincoln University, Jefferson City, Missouri, and from 1973 to 1988 he was a faculty member of the Department of Education at Salisbury State University, where he retired as Professor Emeritus in 1988. Prior to his retirement from Salisbury University, Dr. Chapman had also served as an official and unofficial advisor to his friend Dr. Norman Crawford, a former President of Salisbury University. Dr. Chapman had numerous years of administrative experience and he utilized those years of expertise and skills to mentor others. However, when he retired, it did not mean that he stopped helping others because he volunteered his talents and leaderships skills to co-advise, and eventually advise, the Salisbury University Black Student Union and Salisbury University’s student chapter of the NAACP. Through his numerous national contacts, he was responsible for bringing outstanding leaders and speakers to the Salisbury University cam-pus, such as, the political activist Dick Gregory, the poet Nikki Giovanni, the jazz musician Oscar Peterson, and a host of others. He tirelessly worked to forge relations between Salisbury University and the University of Mary-land Eastern Shore, to improve relations between SU and the community, to provide leadership training for SU students, fraternal organizations, and especially for countless students who were wise enough to listen and learn. Dr. Chapman also volunteered his efforts to help elementary and secondary schools in the area and made the effort to encourage college students to volunteer in after-school programs, both in the evenings and on weekends. His association with the Salisbury University campus did not limit his capacity to work within the Salisbury community and surrounding areas. As a civic leader, Dr. Chapman was on the Board of Directors of Deers Head Medical Center in Salisbury, and as a member of the Board of Medical Examiners of Maryland. He served on many other boards and committees, but he never forgot his roots. He always encouraged students, fraternal and civic organizations and citizens to work together in harmony and in love for the educational, political, social and economic enrichment of the lives of all people on the Shore. Those were his goals and his life’s work remained the same until his death in January of 1994. President of Delaware State University Dr. Oscar J. Chapman 1950-1951 Delaware State University The common factor for Chipman, Cottman and Chapman was Salisbury High School. Chipman was instrumental in the construction of Salisbury High School while Cottman and Chapman both attended the school in order to graduate from the twelfth grade. Even though each of these men served in a different capacity and sometimes at different levels of education, their goals were very similar. Each chose to educate themselves to the best of their abilities, to utilize the resources that were available to them, and then to share their knowledge and skills with their students and their communities at-large. Their entire lives were devoted to education and even upon retirement chose to remain involved in the life of the community and to serve it in some capacity as long as they were physically able. They were life-long learners and encouraged others to do so as well. Those they helped educate were influenced and they in turn impacted others nationwide and beyond. Therefore, Professor Charles Chipman, Dr. Kermit Cottman, and Dr. Oscar J. Chapman rightfully should be known as the 3 C’s of African-American Education on the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

Clara L. Small, Ph.D. Emerita Professor of History Salisbury University Salisbury, Maryland

0 Comments

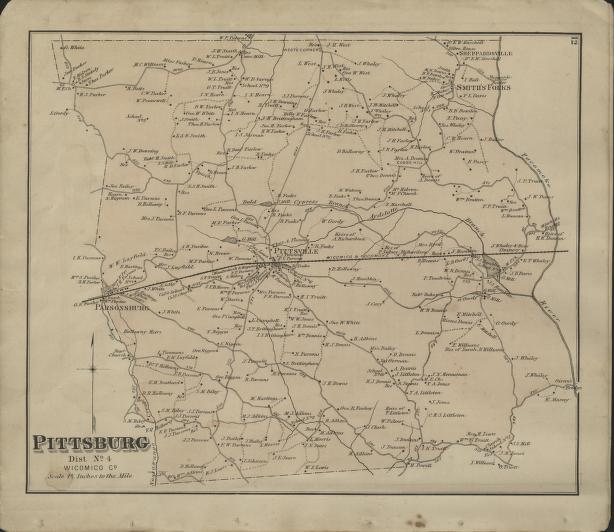

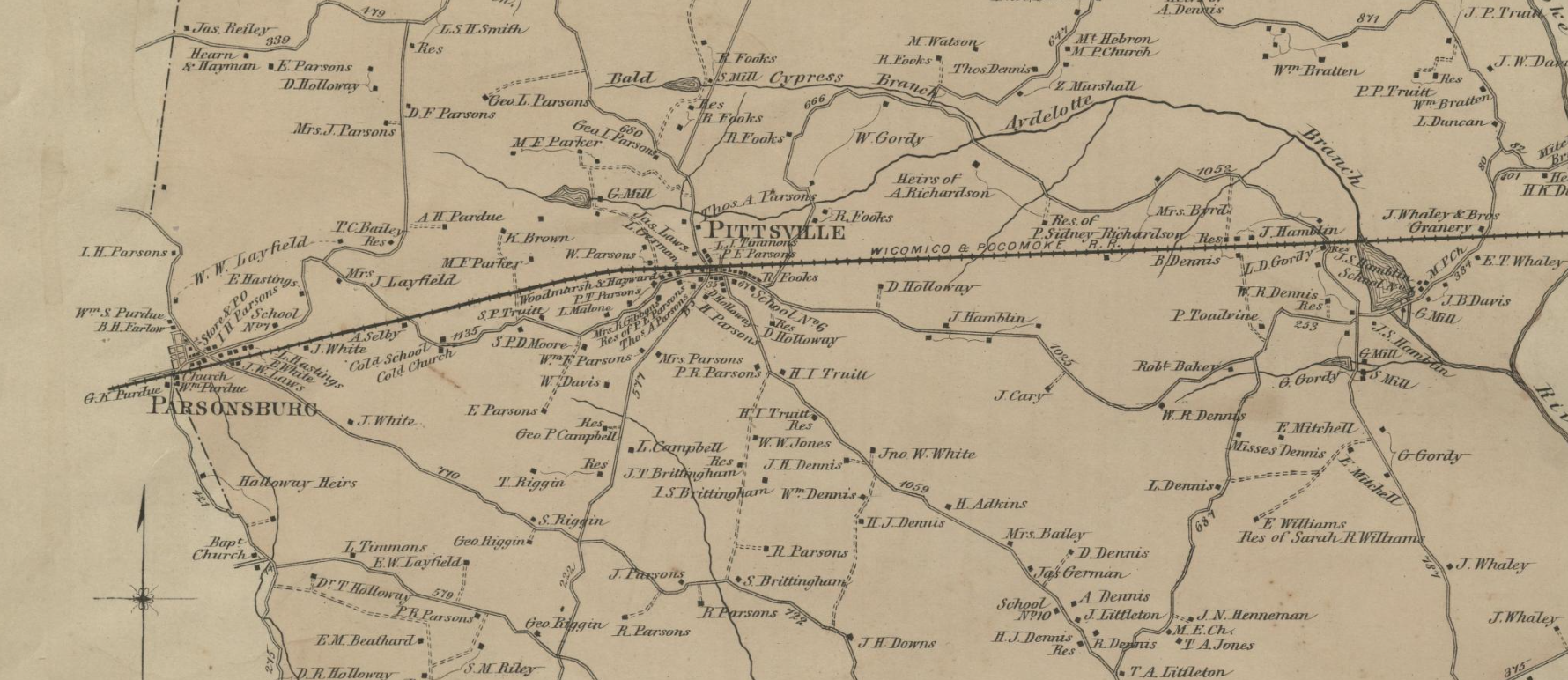

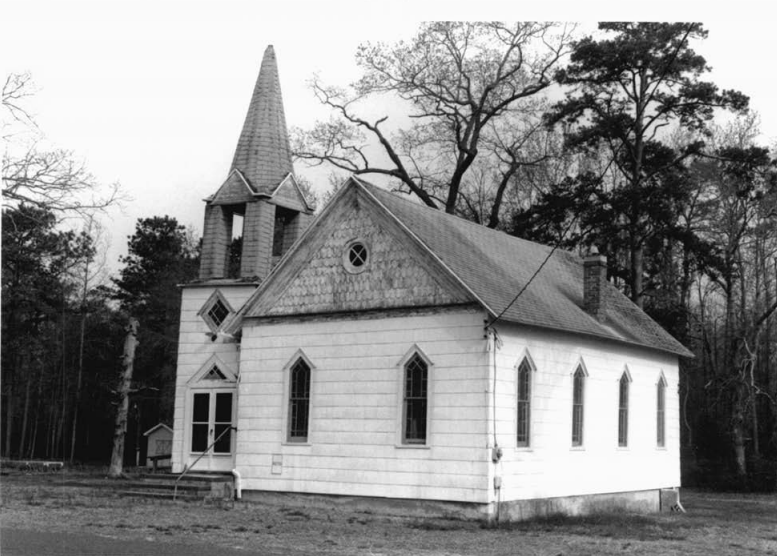

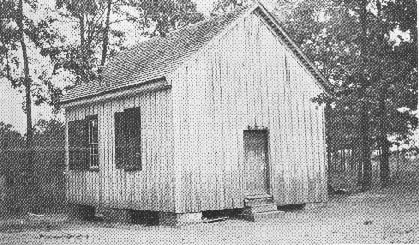

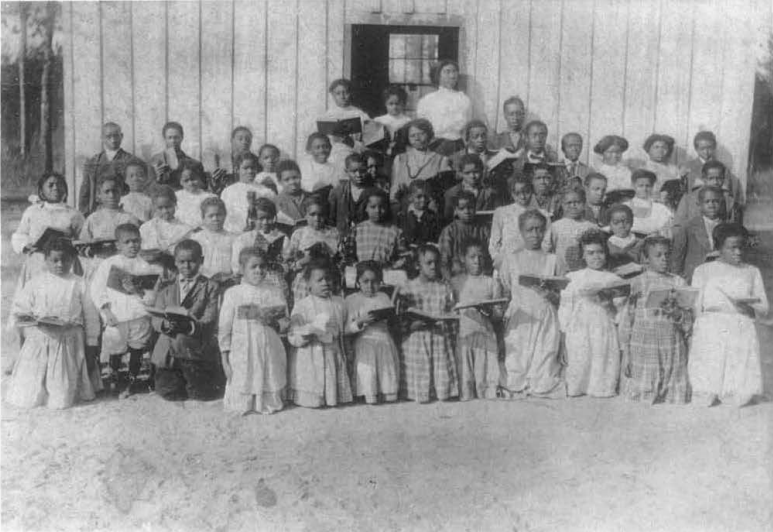

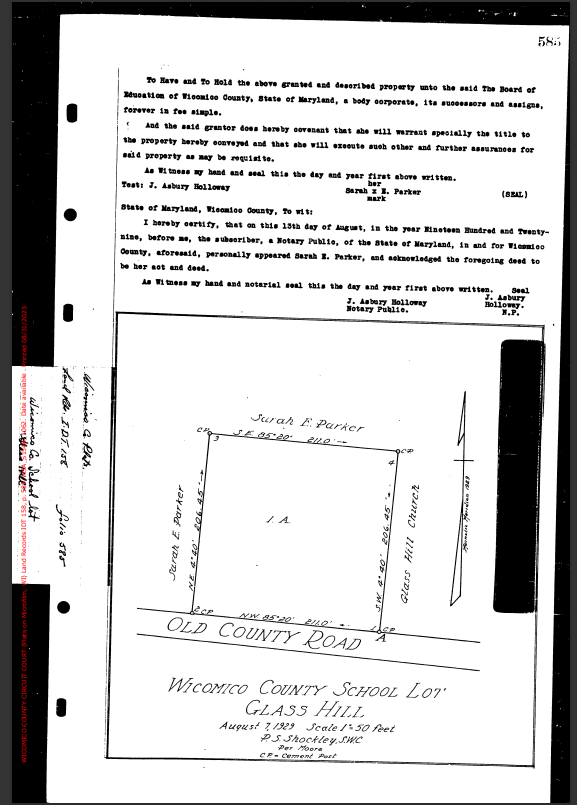

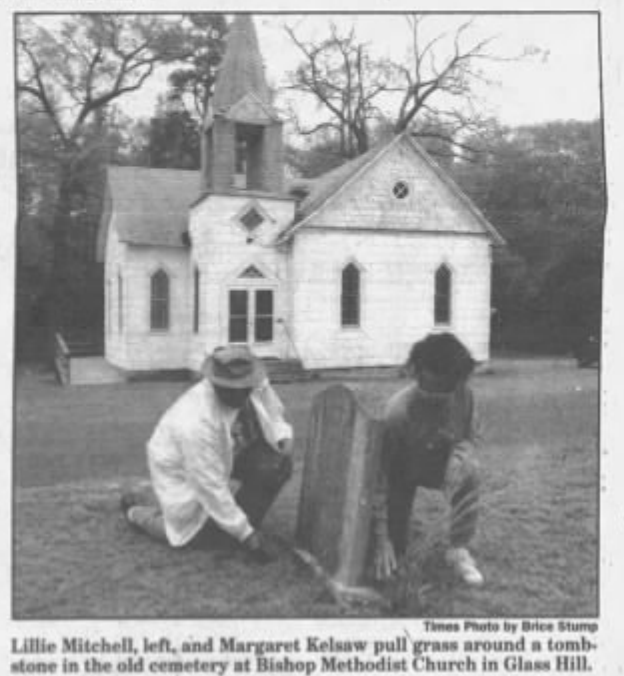

Story by Andre Nieto Jaime Pittsburg District in the 1877 Atlas of Somerset, Wicomico, and Worcester Counties Internet Archive 1877 Tucked in between Parsonsburg and Pittsville in Wicomico County is a small, nearly forgotten community that goes by the name of Glass Hill. When asked, most people likely do not know of its existence nor would they say anything stands out about Glass Hill, aside from the old church and cemetery. This small village is part of Parsonsburg and blends seamlessly into its surroundings. Consisting of a combination of mobile homes and family homes, no one would suspect that this branch of Old Ocean City Road was a Black community with ties going back to the 19th century, possibly even the late 18th century. However, despite emerging around the same time as, or perhaps predating, Derrickson’s Crossroads, Glass Hill and Black rural Wicomico County receive little representation in historical discussion. Yet, Black residents contributed to the history and development of rural towns, like Pittsville and Parsonsburg, which deserves recognition. 1877 Atlas of Somerset, Wicomico, and Worcester Counties Pittsburg District Internet Archive 1877 According to the few remaining residents of Glass Hill in a 1996 article of The Daily Times, Glass Hill’s history dates back as early as the late 18th century as a free Black community. The village’s population continued to grow over the course of the 19th century and after the Civil War, in 1866, a church was built. However, according to the church’s history, it was not named until the 1890s. This very church appears in the Wicomico, Somerset & Worcester Counties Atlas from 1877 as “Cold [Colored] Church” and was later named Bishop Methodist Church in honor of Civil War veteran Jacob Bishop from the community. The Maryland Historical Trust Inventory of Historic Properties refers to the church as “Cavalry M.E. Church” and describes the building as having been built in 1909 because of the inscription on the church’s southeast corner. However, the east side of the corner stone also bears the inscription “Founded in 1872” suggesting that the church may have been remodeled after its initial construction. M.E. Cavalry Church/ Bishop Methodist Church Maryland Historical Trust WI-503 Across from Bishop Methodist Church on the 1877 Atlas was a building labeled “Cold [Colored] School” which was the Glass Hill School, a single room schoolhouse for Black children. According to the Maryland Historical Trust’s Inventory form on the school, it was built around 1870, not long after the construction of the community’s church, and had a lengthy career in educating the children of Glass Hill and surrounding area. According to several articles, such as a 2008 edition of Shoreline, Glass Hill School was home to the first male teacher in Wicomico County, Emerson C. Holloway of Delmar. Glass Hill School also allegedly was where activist Ronald Everett (Dr. Maulana Karenga) attended school. However, a combination of factors go against this claim. References to the school as an active school began declining in the 1940s and the school itself was moved to and restored in Pittsville in the later part of the century. Additionally, an article from 1943 mentions the sale of the Glass Hill School property by the Board of Education of Wicomico County. Finally, the fact that Everett was born in 1941, makes this claim seem to be an extrapolation of the fact that he grew up in Parsonsburg and Glass Hill. Glass Hill School in Glass Hill Delmarva African American History Class Photo Maryland Historical Trust WI-496 Glass Hill School Now in Pittsville 2023 Glass Hill and the schoolhouse also served as the birthplace of the Seventh Tabernacle in Salisbury when its founder, John Elzey Parker, came to visit his sister, Jennie Parker, in 1921 and established his congregation in Glass Hill. Both homes and the Glass Hill School were used to hold services until the congregation moved to Salisbury where it remains active. The construction of the Bishop Methodist Church and the Glass Hill School after the Civil War give the impression that this was a growing community at the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century with the establishment of the Seventh Tabernacle. The community was even slated to get its own Rosenwald School in 1929. According to the United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form on Rosenwald Schools in Maryland from 2014, the final year of Rosenwald School construction was set to be in 1929-1930, with fifteen schools across Maryland being built in this final period of the Rosenwald School Building Program. Glass Hill was among the 15 schools listed in this Property Documentation Form. Searching through land records reveals that in August of 1929 one acre of land was given to the Wicomico Board of Education with the property being named “Wicomico County School Lot Glass Hill” suggesting that this lot was meant to be used for the construction of a Rosenwald School on Old County Road. This transaction was also published in The Daily Times the same month, noting that the Board of Education of Wicomico obtained one acre in the Pittsburg District for the consideration of $10 from Sarah Parker. However, as a future StoryWay will reveal, it is unlikely that this school ever managed to be built. Wicomico County School Lot Glass Hill Wicomico County Circuit Court Plats Microfilm 1929 By the latter half of the 20th century, it seemed that Glass Hill was unfortunately beginning to decline. The 1996 interviews mention how the old homes of Glass Hill were gradually being replaced with mobile homes as the old residents passed on or moved away. Land sales also have contributed to the dwindling of the community. Bishop Methodist Church was not spared from this decline either, with its congregation shrinking to about 15 members by the end of the 20th century. The Great Depression is credited with causing the exodus out of Glass Hill according to the residents. Lillie Mitchell and Margaret Kelsaw Pulling Grass from around Tombstone Times photo by Brice Stump c. 1996 Today, not much remains to remind people that this was once a growing Black community, with only the church and cemetery serving as a reminder of this village’s history. Although, those too face the danger of being forgotten give their current states. Racial barriers not only physically separated Glass Hill from Pittsville and Parsonsburg but have also separated their history from these towns. To preserve the memory of this town and give its residents the recognition that they deserve, several StoryWays will be published delving into the history of Glass Hill as a way of solidifying Glass Hill as a community that grew alongside Pittsville. References: Primary Sources

“Answer to Today’s A Moment in Time.” The Daily Times, February 9, 1998. Atlas of Wicomico, Somerset & Worcester Cos., Md. Philadelphia: Lake, Griffing & Stevenson, 1877. “Building Shore History.” The Daily Times, March 27, 2004. “Deeds Recorded.” The Daily Times, August 16, 1929. “Notice.” The Daily Times, April 14, 1943. Wicomico Co. School Lot Glass Hill. Land Records IDT 158, p. 585 MSA S1548-1062, Wicomico County Circuit Court, Salisbury, MD. https://plats.msa.maryland.gov/pages/unit.aspx?cid=WI&qualifier=S&series=1548&unit=1062&page=adv1&id=1393454667. WI-503 Calvary M. E. Church Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-503, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-503.pdf. WI-496 Glass Hill School Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-503, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-496.pdf. Secondary Sources: Duyer, Linda. “Wicomico County’s Seventh Tabernacle.” Delmarva African American History. Accessed January 2, 2024. https://aahistorydelmarva.wordpress.com/2013/10/03/wicomico-countys-seventh-tabernacle/. National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form “Rosenwald Schools of Maryland.” Maryland’s National Register Properties, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/nr/NRMPSDetail.aspx?MPSId=25. “Remembering the One-Room Schoolhouse.” Shoreline, September 9, 2008. “Seeing Through Time in Glass Hill.” The Daily Times, May 14, 1996. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed