|

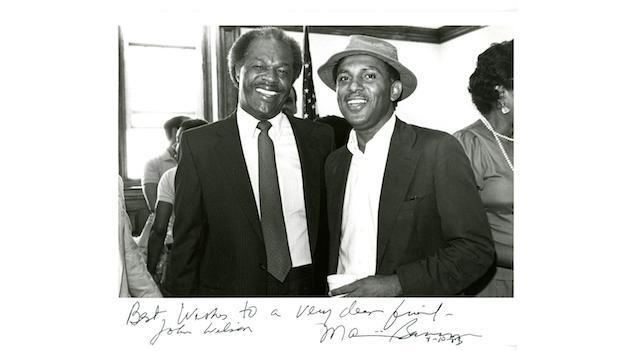

Early life: John Augustus Wilson was born on September 29, 1943 in Baltimore, Maryland, but from an early age was reared by Laura and Walter Maddox, his maternal grandparents in Princess Anne, Maryland. He graduated from the old Somerset High School, which became Kiah Hall, on the University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES) campus. After graduation from high school, he enrolled in the public teachers college for blacks, Bowie State College, now Bowie State University, in Bowie, Maryland. Education: John Wilson’s first attempt to obtain a college education was unsuccessful, so he returned to Princess Anne and enrolled in Maryland State College (MSC), now the UMES, in the spring of 1963, where he majored in physical education. His time at MSC coincided with student protests nationwide. MSC students struggled to achieve equal treatment in Princess Anne when they learned that a desegregation agreement that had been negotiated by the Princess Anne Biracial Committee had been broken. On February 20, 1964, the MSC students were led by John “Johnny” Wilson, and community leaders Warren Morgan, Reverend Autry Cash and Curtis Gentry, went into the town of Princess Anne and sought service at the local restaurants. They were served at all but two restaurants. Civil Rights Activist: On the second day of the protests, a door hinge was strung. On the charge of destruction of property, Johnny Wilson was arrested on the MSC campus by Maryland State Troopers, on the belief that his arrest would end the protests. Contrary to that belief, Wilson’s fellow protestors placed themselves on the street directly in front of the patrol car which prevented the troopers from leaving cam-pus with Wilson. He was released and the police left the campus, but later that day Wilson went to the jail and turned himself in to the authorities. The protestors were committed to nonviolence, but the home of J. Leon Gates, an MSC accountant and Johnny Wilson’s uncle, was bombed, and a cross was burned in view of the campus. The students continued to protest the injustices and were attacked and bitten by police dogs, were beaten by baton wield-ing policemen, were called derogatory names, and were also blasted by high pressured fire hoses. Johnny Wilson was again arrested with nearly 30 other students. The students continued to protest and received support from as far away as Denmark and Austria. Local support came from Gloria Richardson, a civil rights leader from Cambridge, who marched with the students. Other support came from the comedian, author, political activist, Dick Gregory, who arrived in Princess Anne and offered financial and moral support. He proposed a boycott of the town, which was effective because MSC was the major source of profit for Princess Anne, and town, state and government officials took note of that fact. A meeting was arranged for the students to meet with Governor Tawes at the State House in Annapolis. It was ironic that the same State Police who had beaten the students and trained dogs on them had to chauffeur them to and from the meet-ing. At the meeting, the Governor promised that an accommodation act which guaranteed equal access to restaurants, hotels, etc., would extend to the Eastern Shore, and the protests ended. The protests put Johnny Wilson into the eyes of the media. Wilson did not complete his education at MSC. Instead, he left Princess Anne and became involved in the national civil rights movement, and allied himself with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Wilson also became close colleagues of Dick Gregory, Malcolm X, Congressman Allen Clayton Powell, Jr., and he work-ed alongside Marion Barry, the future Mayor of Washington, D.C., and future longtime Georgia Congressman John Lewis. Home Rule Charter: In the 1960s, John Wilson became a leading advocate of home rule for Washington, D.C. In 1974, Wilson served as the Chairman of the drive to approve the referendum to adopt the Home Rule Charter for the District of Columbia. The Charter allowed residents for the first time to elect both a mayor and a 13-member City Council called the Council of the District of Columbia. In 1974, Wilson was elected and won a City Council seat on the first D.C. Council. Wilson was a unifier, who brought rich, poor, young and old together. He had the audacity to tell people what he thought, criticized them to their faces regardless of who they were, and somehow they respected him in spite of it. He chaired the Finance Committee of D.C. before he was elected chairman of the Council in 1990. Some members of the city government and assistants of the Mayor’s Office referred to Wilson, “as a wizard in municipal finances.” Wilson believed that the government had to be healthy in order for it to function properly. Political Career: John Wilson served 18 years as an elected official, including two years as a D.C. Council Chairman. He was a champion of the underprivileged and disenfranchised, used his political skill to push through legislation on rent control, child abuse prevention, tax reform, consumer protection and victim rights. He was instrumental in getting legislation passed that included limits on converting rental housing to condominiums, gun control, and expanded medical care for women and children. Wilson also wrote the District’s tough anti-hate crimes laws as well as its human rights laws. For all that he tried to do, John Wilson was considered to have been “one of the most powerful and most popular men in D.C. politics.” Some people even thought he would run for the office of Mayor of D.C. Death: Unfortunately, on May 19, 1993, John A. Wilson was found deceased. His death was ruled a suicide based on the belief of the pressures of the job, a promising political career, possibly personal concerns, coupled with a guarded history of medical concerns, all may have loomed too large. His untimely death shocked everyone because he was described as a beacon of hope for everyone as he tried to improve the lives of others. In 1994, the District of Columbia municipal government building was named in his honor. A private drive off Backbone Road at the edge of UMES bears the name of “John Wilson Lane.” UMES also has two scholarship funds named in his honor. Therefore, John A. Wilson’s legacy lives through scholarships to help educate others. However, on a grand scale, according to John Wilson’s former math professor and President of UMES, Dr. William P. Hytche, “his [Wilson’s] legacy lies in his desire to make life better for other people.”

0 Comments

The Unforgettable Legacy of Kermit Travers, Sr.: Journeying with the Last Black Skipjack Captain5/19/2023 Early Life: Kermit Robert Lee Travers, Sr. was born August 13, 1937 to Mable Pritchett Travers and George Travers in the Blackwater region of Dorchester County, eighteen miles east of Cambridge, Maryland. He was a part of a blended family of 12 children, but he was the only boy of nine children born to his parents. Kermit grew up in the poor, segregated backwater neighborhood among the water marshes and creek edges of the Honga, Blackwater and Choptank Rivers. Born just two years before the end of the Great Depression (1929-1939), when banks collapsed, businesses closed, homes were foreclosed, some people were reduced to starvation, and many of those who were employed as share-croppers and tenant farmers were forced off the land they worked. Even the most enterprising individuals found it difficult to care for their families. Few government agencies existed at that time to help families in dire straits. In many in-stances, those few who found employment were hired but were never paid. Kermit’s family was extremely poor, and they lived in an old two-story house that had little or no insulation as they could see through the cracks in the structure, which forced them to put paper and rags into the holes when it snowed. Nor did they have plumbing or running water, so the family trekked about a quarter of a mile to Kermit’s uncle’s residence for water. The rule of thumb was that there was no wasting of water. The family lived off the land and hunted for squirrels, rabbits, black birds, turtles, and raised ducks for subsistence. Just before Christmas, they killed 6 or 8 hogs and stored the meat. The family’s struggle to survive was so acute that for Christmas, Kermit often received hand-me-downs as gifts. As early as six years of age, Kermit learned to shoot a rifle to hunt animals in order to help feed the family and to cut wood to heat the house and to use it as fuel to cook their food. He also helped his father cut wood and hauled it on his shoulders out of the woods to sell to others. Education: Kermit began school at the age of six, but the survival of his family was a major concern. At the age of seven, he began to seek ways to help the family, and found employment in crab houses shucking oysters. He sought any type of work that would benefit the family, which meant that his desire to obtain an edu-cation and to become the first in the family to obtain a high school diploma be-came secondary. As a result, Kermit’s attendance at school was sporadic at best, as he worked on any job he could find to help support the family. Survival of the family was his major concern, coupled with his father’s illness, forced Kermit to quit school in the 10th grade, and he was forced to become a man before he wanted or truly understood the reason. At 15 or 16 years of age, he continuously sought gainful employment, and he was introduced to work on the water. By eighteen, he actively began to work on the water, but it did not produce enough funds for his family to survive. By the age of 18, he began to have a family of his own, but he was not making enough money to properly care for them, his mother, and siblings. Kermit even went to Florida in search of sufficient employment, but he soon returned to Cambridge because the situation there was no better than when he left Cambridge. In 1958, at the age of twenty-one, he accepted a job working with his uncle in New Jersey and learned to work on a tonging boat. No job was beneath Kermit. He soon found employment with Captain Eugene Wheatley, who taught Kermit all of the tasks that were required to operate a skipjack. Captain Wheatley was not in the best of health, and Kermit realized that someone had to be knowledgeable about the operation of the boat in an emergency if Captain Wheatley became ill or incapacitated. Wheatley taught Kermit the duties and responsibilities of being a captain, even though he did not want to be one at that time. Kermit worked with Wheatley and remained on his boat, the Lady Katie, for 15 years, was installed as a skipjack, and became one of only five known African Americans to captain a skipjack on Chesapeake Bay waters. Work on the water was not easy. In spite of the dangers of the job, Kermit survived many situations, including: a number of serious injuries, that caused life-threatening accidents, explosions, and fires on board; capsized boats that included the drownings or near drownings of close friends, relatives and associates; governmental regulations that threatened the future of oystering; and the future employment of watermen prompted by the death of the seafood industry. For example on one fateful day in 1975, the captain of the Somerset ran into Kermit’s boat and injured his crew. The accident busted a 55-gallon drum of gasoline, broke the sails, and set the boat afire. No one came to their aid because of the fire. One member of the crew was so severely burned that when the wind hit him, his skin began to peel. As the fire continued to blaze, someone on the Tidewater Fishery threw two fire extinguishers on board the boat. Kermit and the crew threw the drums overboard, but no one could get close to their boat. Kermit went below deck and put out the fire, and he never got a singe. Kermit’s hands were so firmly attached to the fire extinguishers that those who came on board the ship to help them used a screw driver to pry Kermit’s hands from the extinguishers. From that point on, Kermit was called “The Devil,” because he had walked through the fire to extinguish it. The reason Kermit did not jump over-board and abandon the ship during the fire was because he could not swim. He had rationalized that over the years that he could not swim and save himself, but he had learned to balance himself, or he would fall off the boat and drown. Kermit had been injured more than once, was incapacitated for 6 or 7 years, and emphatically stated that he was not going back on the water. How-ever, the lure of the water pulled him back. The love of the water and the sense of freedom he found on the water kept him there. He believed that there was little or no racism or discrimination on the water because work on the water demanded that Blacks and Whites cooperate with each other for survival. It was only when the watermen returned to the land that racism and discrimination existed. For Kermit and other watermen, life on the water was relatively color blind. When work on the water was unfruitful or out of season, Kermit worked as a Dorchester County Sheriff Deputy. He was employed from 1976-1985 by the Dorchester County Board of Education in conjunction with the Sheriff’s Department, primarily at Cambridge High School, because some of the children were disorderly, fought each other, set off cherry bombs, vandalized the school, and committed other offenses. The goal was to maintain peace in the school. For many years, Kermit did not wear a uniform while working at the school. He did not believe that suspending students from school was beneficial because he felt students needed all the education they could get. He understood the value of education because he did not have the opportunity to acquire the education he so desperately desired in his youth. When things were relatively quiet in the school, Kermit often visited the classrooms and listened to the teachers as they taught various lessons. He used those opportunities to deal with the students directly and encouraged them to learn as much as possible. Kermit found employment whenever and wherever he could. He also worked as a contractor. He went to Hattiesburg, Mississippi for five or six months and while there, he trained and became a contractor. While there, he also took night classes in Criminology and earned his high school diploma. His original goal was to remain in Mississippi, but due to a death in the family, he returned to the Eastern Shore of Maryland, obtained a contractor’s license, and began his con-tractor business. His work as a contractor required him to find able-bodied employees to work in the fields to harvest cucumbers, beans, tomatoes, and other fruits and vegetables. Kermit labored as a licensed contractor from 1973 to 1985. He was so well-known that within 24 hours he could get over 200 or 300 employees in the fields. As a result of his speed in delivering workers for big producers, he obtained a reputation for getting a job done. The workers were loyal to him because he transported them to and from the fields, paid them daily and paid them more than the other contractors, which assured him that he would have an ample supply of workers. Those workers included Mexicans, African Americans, Haitians, a host of unemployed individuals, and high school students who used their funds to purchase school clothing and to pay for extracurricular events. Kermit also got people out of jails and prisons and found jobs for them. However, once the harvests were over, Kermit found employment in other ways. He worked on a farm with a local family, split logs, worked in various crab and oyster houses, painted houses, and sold wood for Dorchester County Social Services. He was so swift in shucking oysters that numerous restaurants, such as Suicide Bridge, the Hyatt in Cambridge, and others paid him to shuck oysters on the half-shell on some Friday nights because the workers could not keep up with the demand from the customers. In short, Kermit Travers was as he called it a “Hustler,” as he found various means to care for his family. Regardless of the many jobs he held, his love was always the water, the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. He often stated, “He would rather work on a boat than anywhere else,” because he loved being around boats, oystering and everything associated with the water, due to the sense of freedom it provided. Being on the water became so much a part of his being that if you observe Captain Travers and other watermen, you will see that even when many of them are not on the water, they still rock or sway as if they are still on the boats be-cause it is a part of their rhythm of life. He and they also stand with their feet apart so that they are sure-footed and are firmly planted on the boat. After more than three decades on the water and many years as the last African American Skipjack Captain, Kermit Travers will never lose his love of the Chesapeake Bay and the bounty of it resources. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed