|

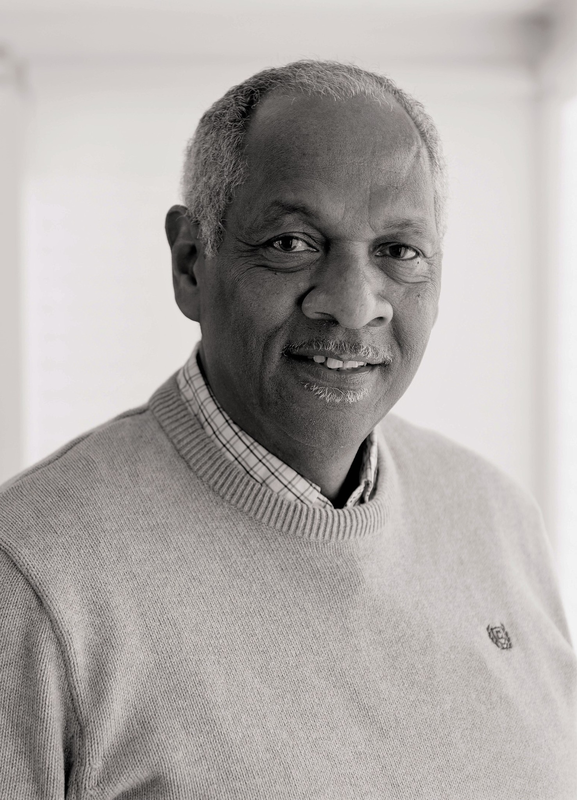

Patrick Henry was born in February of 1952 in Berlin, Maryland to Samuel Henry, Sr., a Navy veteran of World War II, and Marigold Kee Henry from Seaboard, North Carolina. Reared on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, Patrick’s primary and elementary education was at the Flower Street Elementary School in Berlin, and his freshman year of high school was at Worcester County High School. In the fall of 1965, with the integration of the public schools, Patrick attended Stephen Decatur High School, from which he graduated in 1970. He did not attend college immediately following graduation from high school, but several months later he enrolled in Maryland State College, now the University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES). At UMES, he majored in art, something he developed an interest in at an early age, but he was basically self-taught. He began painting by numbers when he was a student at Flower Street School. His interest in oil painting and painting began about age 14 or 15. His first painting was sold in 1968 while he was still in high school. Most of his early subjects were of his environment, of servitude, and black leaders, such as Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Stokely Carmichael, H. Rapp Brown, and others of that era. At UMES, his master professors were Ernie Satchell and Jimmie Mosely, his mentor and the art professor for whom the Mosely Gallery at UMES was named. While studying at UMES, Patrick Henry was judged the Most Talented Student. He graduated from UMES in 1975 and was the first in his family to graduate from college. His graduation was a joyous occasion, but it was also a very sad time of his life because his father passed away about the same period. Upon graduation from college, Patrick’s first teaching job was teaching art at his alma mater, Stephen Decatur High School. After two years of teaching, he made the decision to leave the teaching profession and to pursue his art on a permanent basis. His goal was to attend Virginia Commonwealth University and obtain a master’s degree in Art Education. Unfortunately, due to a family crisis, he was asked to return home. He returned to Berlin, helped his brothers with masonry, construction and maintenance work, and pursued oil painting on a part-time basis. However, by the 1980’s, he began to actively pursue his passion. For thirty years, the environment of the Eastern Shore dominated his canvasses. He referred to the Shore as... ...”a land of people: watermen, farmers, brick masons, teachers and day laborers. They live their lives intertwined-knowing each other and the land around them with a depth of knowledge that is not forgotten as the years go by and as the people and the land changed." For Patrick Henry, art is his passion, and he has compared art to his heart beat. For Patrick, art and his heart beat, are synonymous with his existence. They are as intertwined as the land and people of the Eastern Shore of Maryland. Art was also a challenge for him, especially in a place where there is often no appreciation of art, often a lack of understanding of its value, or a need for financial assistance for it to survive or thrive. By the late 1980’s and early 1990’s, Patrick Henry was solely involved in honing his craft and participated in numerous exhibitions throughout the Mid-Atlantic region and various galleries on and off of the Eastern Shore. A show in Annapolis, Maryland exposed his work to collectors beyond the Eastern Shore. A major mural commission at Atlantic General Hospital highlighted his career in the 1990s and his pen and oil graphics were marketed through t-shirts, tote bags and other printed art products. In1996, Patrick was the recipient of the Berlin Award, presented annually to an individual who has by unselfish efforts and dedication, made outstanding contributions in service to the Town of Berlin and the immediate region. Patrick Henry has presented numerous exhibits and as a result has been the recipient of various awards and accolades, including the following: • “Moments: In Color, Geometry, Texture and Light,” which premiered at the Ocean City Center on the Arts, July of 2015. • ‘Ephemeral Moments,’ an exhibit held at the Academy Art Museum in Easton, Maryland, February 4-April 1, 2012. • The “Amusement” series, a 27-piece collection which depicted some of Ocean City’s most memorable amusement and entertainment features was completed. Some of the pieces were purchased as the fifth addition to the Artists of the Eastern Shore Collection established by Dr. Amy Stephens Meekins and family. (2011) The original oil painting ‘Trimper’s Luna Park, Ocean City, Maryland-circa 1925, is prominently displayed in the Teacher Education and Technology Center (TETC), now Conway Hall, at Salisbury University, Salisbury. • The Maryland Life Magazine selected Patrick Henry as the Lower Eastern Shore’s Finest Artist in 2011. • Patrick’s paintings titled “Up! Up! And Away” and “Foggy Harbor-West Ocean City” were added to “Berlin Milling Company” (originally bought by the Reginald Lewis Museum in 2010) became a part of the Reginald Lewis Museum Permanent Art Collection, October 31, 2014. • “Points of Juxtaposition: A Gathering of Eight African-American Artists” was presented at the Mosley Gallery at UMES, February 1-26, 2010. • “Maryland Artist Showcase: Works of Art by Patrick Henry” was presented at the Reginald Lewis Museum, in 2008. • “Patrick Henry: Into the Light,” exhibit was held at the Reginald Lewis Museum of African American History and Culture in Baltimore, Maryland, 2007. • Patrick Henry was named “Delmarva’s Best Local Artist” by Salisbury’s The Daily Times, Salisbury, Maryland, 2005. Over the years, Patrick’s horizon has been broadened and included other subjects than the Eastern Shore. He is also working in a special program to encourage young protégés. The four facets of the program are visual, musical, performing arts, and literary arts. The ultimate goal of the program is to inspire young people to appreciate art, to become great artists, to preserve art and to help it thrive. Patrick also believes that if artists can conquer the seven deadly negative curses of doubt, fear, guilt, limiting beliefs, self-sabotage, jealousy, and addiction, and replace them with positive beliefs of courage, freedom, limitless possibilities, self-love, self-worth, and abstinence, they can succeed. As such, Patrick hopes to mentor young artists, help them believe in their passions, and encourage them to succeed as artists and in life. Even though Patrick’s paintings primarily focuses on rural life and the environment on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, his art inspires others to remember the past and scenes that are rapidly fading from the landscape and their collective memories. Recently, Patrick has presented exhibits at the Germantown School Community Heritage Center in Berlin and the Ward Museum in Salisbury, among other venues. The exhibits at those two locations, showed photographs of local individuals from the Berlin area that had been saved and originally stored in a never-used dishwasher. The photographs included those of African American children at play, displays of vintage automobiles, and workers at a former mansion, among other subjects. A September 2023 exhibit, the “Phillips Canning Factory Show,” is presently on display at the Germantown School Community Heritage Center. The exhibit highlights the operations of the canning factories on the Eastern Shore and its impact on the area through photographs and memories of the people of the local area. It also focuses on the often overlooked cultural impact upon the lives of the people who toiled there, especially many of the women. The exhibit focuses on the canning industry, but it also captures the experiences and memories of many of those women who were employed there, as they worked to supplement their families’ income, to survive, and to care for their families. Patrick Henry is a multi-faceted artist whose roots are deeply imbedded in the Eastern Shore. His portraits and paintings of rural, environmental landscapes, and paintings of local individuals tells a thousand stories of strife and successes, while simultaneously depicting the lives of people who toiled so that future generations could survive and thrive. Patrick’s works show that we are who we are because of the subjects he depicts and that the present generation is standing on their shoulders. As such, it is our responsibility to remember those who paved the way for present and future generations. Patrick Henry, a renowned artist, is also a historical artist, who preserves local Eastern Shore history and culture through his art. Dr. Clara Small

0 Comments

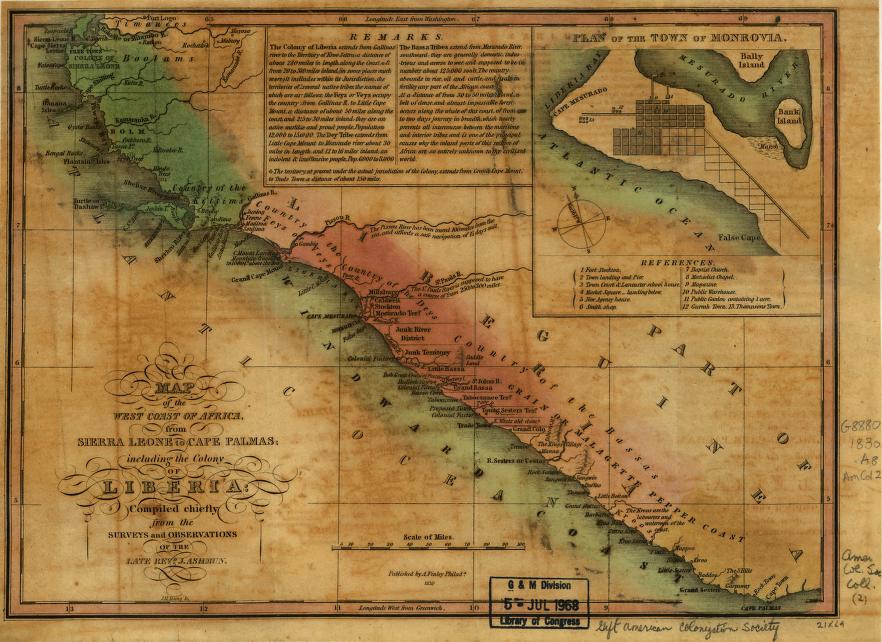

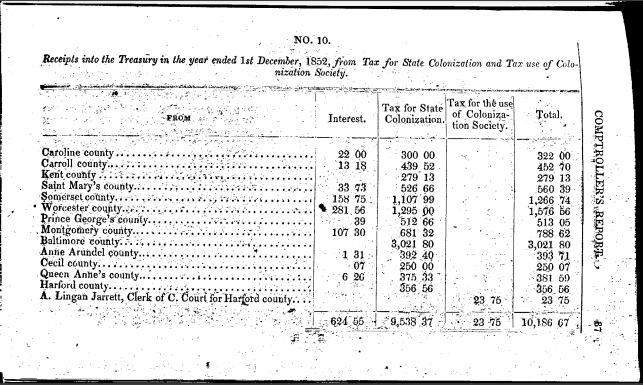

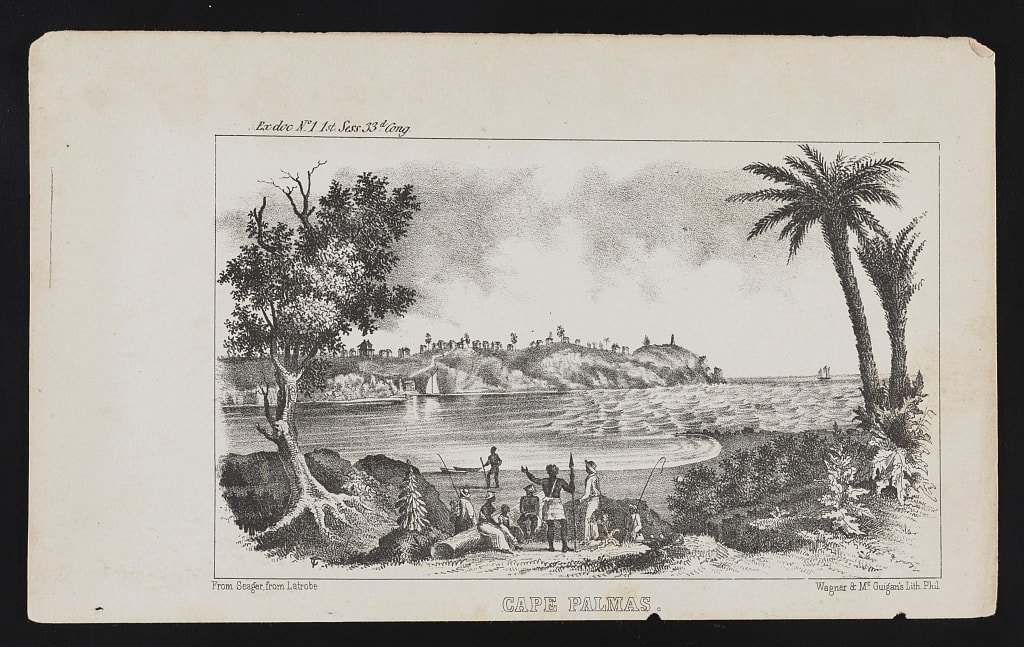

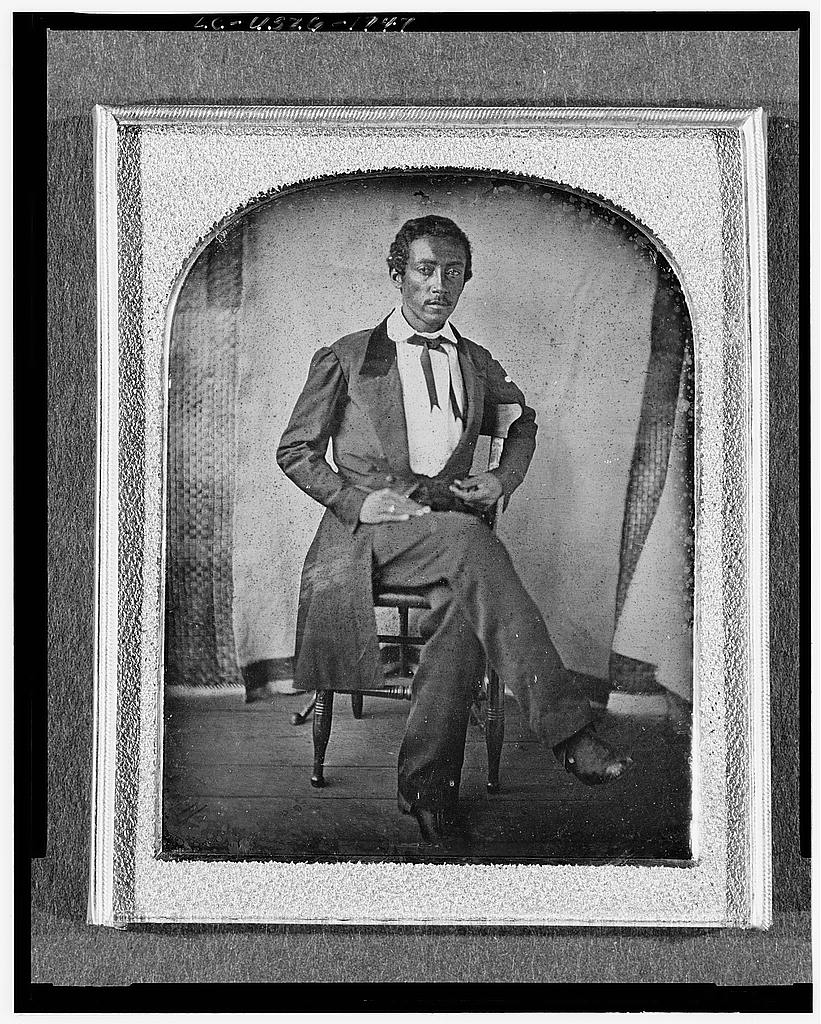

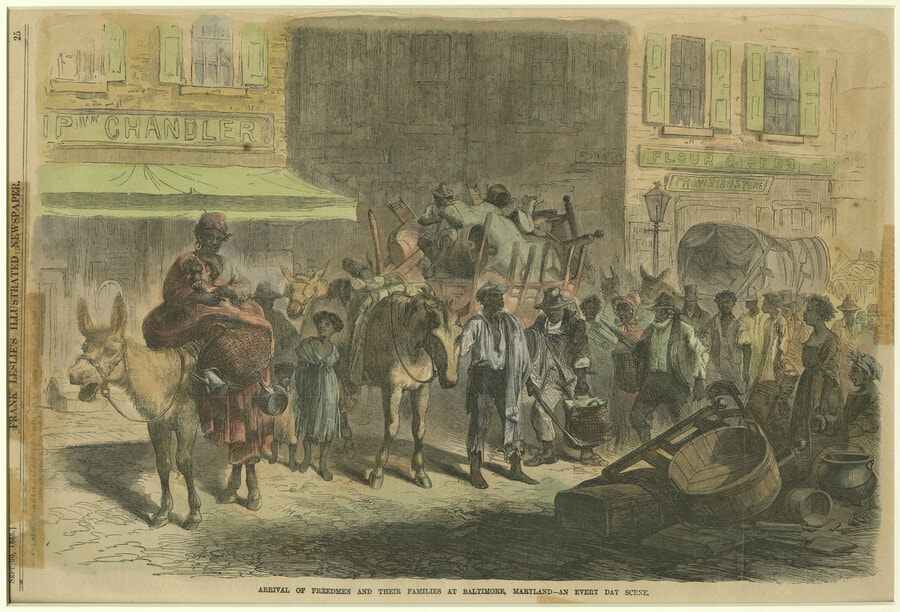

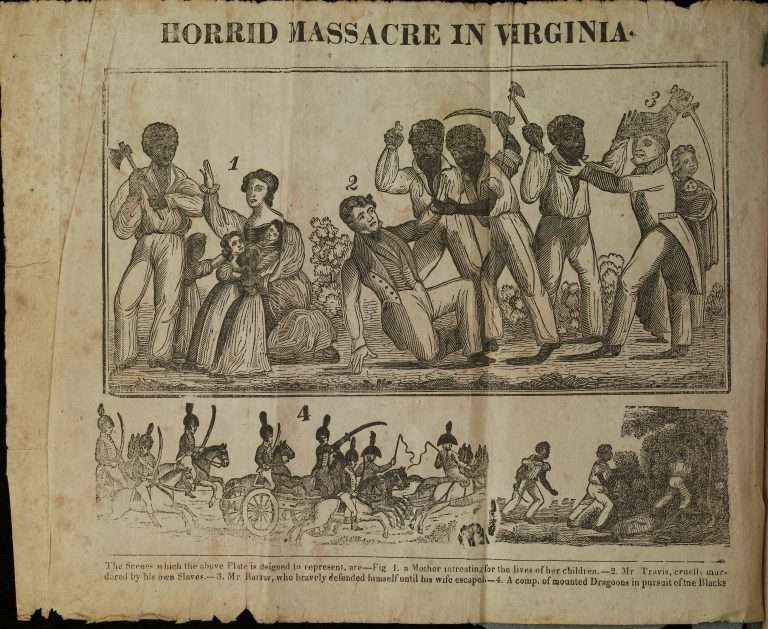

Map of the West Coast of Africa from Sierra Leone to Cape Palmas, including the colony of Liberia Library of Congress 1830 Foundation of the American Colonization Society and the Maryland State Colonization SocietyIn late 1816 the American Colonization Society (ACS) was founded to expatriate free Black Americans to Africa. Soon after, auxiliary branches of the ACS formed in several states, of which Maryland was a prominent branch. They all shared the goal of giving freed African Americans equality and freedom denied to them in American society. However, this came with a catch. To claim this promised liberty, African Americans had to leave the United States for the continent of their forefathers. Many decided to take the risk and emigrated to what would become Liberia. From 1820 until 1860 10,939 people of African descent took up the ACS on its offer and left for Liberia. However, most African Americans felt that the U.S. was their homeland and that emigrating to Africa was out of the question. Many abolitionists also condemned the idea of colonization for not actually addressing the issue of slavery. The concept of colonization to address the peculiar institution was nothing new. In the late 18th century during the American revolutionary period there were talks of emancipating and relocating the Black population elsewhere, with Thomas Jefferson himself proposing the idea in 1777. Jefferson even considered the idea of resettling African Americans to the British colony of Sierra Leone during his presidency. In the early 19th century politicians like Charles Fenton Mercer and even religious figures such as Reverend Robert S. Finley took an interest in the idea of colonization. By the end of 1816 the ACS was founded and six years later, in 1822 Liberia was established. By 1825 the colonization movement was widespread across the U.S. due to the increased racial tensions between White and free Black Americans. The Maryland State Colonization Society (MSCS) was founded on the heels of the ACS in 1817. This organization was supported through taxes as well as fees that were paid to be used by the MSCS while registering slaves brought into the state. This is seen when in 1841 a man by the name of Henry P. Norris registered an enslaved girl named Eliza at the clerk’s office in Worcester County and paid a $15 fee for use in colonization. The MSCS ultimately split from the ACS and acted on its own for the most part, but they both shared very similar goals and fears. Maryland saw its free Black population as a growing problem, as Maryland was the state with the largest free African American population in the United States. Nat Turner’s rebellion in 1831 sparked even greater concern about the free Black population, believing that they would incite similar rebellions if left unchecked. Colonization provided Maryland with a convenient solution to their troubles. In February of 1834 the MSCS established its own colony at Cape Palmas, creatively named Maryland in Liberia. By 1856 over one thousand African Americans had decided to leave Maryland for Africa. Receipts into the Treasury in the year ended 1st December, 1852, Report of the Comptroller, 1852, Volume 196, Page 37 Maryland State Archives 1852 Cape Palmas Library of Congress 1854 Support from African AmericansOne Connecticut newspaper from 1829 included an account from Reverend George M’Gill (likely McGill), a Black preacher from Baltimore, who went to Liberia. Here, it was emphasized that M’Gill was a respected man within the Black community. M’Gill’s words were quoted: “I am satisfied that Africa is the place for me and mine, and all others of my colour… Nothing could induce me to remain in America.” M’Gill was very vocal about his support for colonization, seeing it as a suitable home for himself and other African Americans that were not accepted in the land of their birth. By emphasizing M’Gill’s authority as a respected preacher, the paper aims to convince other free African Americans that colonization is supported by Black people themselves. These claims of prosperity and of Black freedom were meant to coax free Black Americans to emigrate to Liberia with many seeing Liberia as an opportunity for the freedom denied to them in the U.S. R. McGill, full-length portrait, seated in chair, facing front, with textile screen in background Library of Congress C. 1840-1860 Opposition Yet, most Black Americans remained unconvinced about colonization. They doubted the sincerity of the ACS and often saw it simply a ploy to strengthen slavery. William Watkins, a Black anti-colonial activist from Maryland, expressed this doubt in his 1827 letter to Freedom’s Journal. Watkins recognized that he should be enthusiastic about any attempts to improve the status and condition of the Black American. This idea was quickly dropped, and he began to criticize the “African Colonization Society” and their supposed benevolence and philanthropy. Watkins sees flaws with the society, saying, “It appears strange to me that those benevolent men should feel so much for the condition of the free coloured people, and at the same, cannot sympathize in the least degree, with those whose condition appeals so much louder to their humanity and benevolence.” Watkins is suspicious of the sincerity of the ACS’ concern for the Black population, arguing that the ACS did not have the slightest idea about the free Black experience and that the society has ulterior motives. Without explicitly saying so, he calls out the Society for being led by the White elite that was set out to promote its own interests, not the interests of free Black people. Another reason that free African Americans from Maryland rejected colonization was that they adamantly held that Maryland was their home. In the same letter to Freedom’s Journal, William Watkins demanded answers to several very important questions. Watkins asks, “Why this strong aversion to being united to us?… Why this desire to be so remotely alienated from us?” Watkins insisted on knowing why the ACS was so dead set on removing free African Americans from the U.S and why there was no discussion about the potential for Black and White American unity. He finds it baffling that free Black Americans must leave the place they were born and consider to be their “veritable home” for their economic, political, and social standing to be improved. This sentiment was repeated time and again by Black Marylanders and Americans throughout the 19th century. Arrival of Freedmen and Their Families at Baltimore, Maryland - an Every Day Scene Maryland Center for History and Culture 1865 Act of 1832Maryland’s legislature, seeing that free African Americans preferred Maryland over Liberia and terrified by Nat Turner’s Slave Rebellion in 1831, took measures to force the consideration of colonization. During the 1831-1832 session, an act was passed that created a board tasked with relocating the freed Black population, and any slaves emancipated in the future, to Liberia or elsewhere outside of the state. Additionally, the law required manumissions to be reported to this board along with, including the individual’s name and age. From the board, information regarding any newly emancipated slaves was required to be passed down to the ACS or the MSCS so that they could take action to send the manumitted person to Liberia. The act was worded in a way to make it appear as if emigration to Liberia was voluntary, claiming that African Americans “may be willing to remove out of the state to the colony of Liberia… or to such other place or places, out of the limits of the state” and “shall consent to go,” but this was far from the case. If the individual refused the offer to leave the state then “it shall be the duty of the said board of managers to remove the said person or persons… beyond the limits of this state” according to the act. If there was resistance to leave Maryland, the board was to inform the local sheriff who was then to arrest the individual and forcibly take them out of Maryland. This, of course, was quickly denounced. An 1833 issue of The Abolitionist contains a story titled “Patriotism and Benevolence of the Colonization Society” which was quick to point out the hypocrisy of the MSCS, bringing attention to what is to happen if an individual refuses removal. This policy was denounced as “cruel and tyrannical,” and as not giving slaves any real choice in regards to their freedom. The author reaffirmed their belief that every slave that is emancipated in Maryland has just as much of a right to live in Maryland as a White American does. Horrid Massacre University of Virginia Special Collections 1831 End of ColonizationLiberia declared independence in 1847 and Maryland in Liberia unanimously voted for independence in 1853. By the Civil War African American interest in leaving for Liberia peaked due to lost hope in their situation improving. Abraham Lincoln himself even considered colonization as an option to keep the border states from seceding during the Civil War. Abolition after the Civil War rekindled the hope of racial equality at home and put the final nail in the coffin for colonization. Despite being ostracized by White society, free African Americans throughout the 19th century adamantly rejected the idea of forging a new life in Liberia. Instead, they would fight for civil rights at home, even into the late 20th century, maintaining for over a century that the U.S. was their true home and that coexistence between White and Black Americans was possible.

Andre Nieto Jaime (B.A. History) AmeriCorps Volunteer September 9, 2023 |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed