|

Wilmore Leonard is pictured in front, second from left Photo Courtesy of the Charles H. Chipman Center Wilmore Brown Leonard was born December 30, 1916 to Katherine Brown Leonard and Howard E. Leonard, and was reared on Board Street, in Salisbury, Maryland. He graduated from Salisbury Colored High School. After high school, he entered and graduated from Hampton Institute, now Hampton University, in Hampton, Virginia, in 1939 with a bachelor’s degree in science. While at Hampton Institute, he was Captain of the Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC).

After graduating from Hampton Institute, Wilmore Leonard taught for two years at Accomack County High School in Parksley, Virginia. By 1941, World War II had begun and Leonard volunteered for the United States Army Air Corps in the fall of 1941 and was accepted in January of 1942. However, it was not easy for African American men to serve in the United States segregated military forces. At the time, they had to fight for the right to serve in other than menial jobs. However, due to protests against racism and segregation led by the black civilian workforce, black women’s groups, black college students, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and an interracial coalition that resisted inequality in the fighting forces, blacks were reluctantly allowed to enlist in the newly created United States Air Force. Despite opposition to the contrary, First Lady of the United States, Eleanor Roosevelt took a flight with one of the black pilots who became known as the Tuskegee Airmen. A combination of those groups and their protests combined with Mrs. Roosevelt’s bold stance helped to change some of the skepticism about the black pilots and their abilities to fly aircrafts. It was in January of 1941 that the United States War Department announced the formation of an all-black pursuit squadron of fighter planes and the creation of the training program at Tuskegee Army Air Field, Tuskegee, Alabama, for black pilots. White officers questioned the physical and mental ability of black men to serve or pilot fighter air craft. Unlike the rest of the Army, the 99th Squadron and the 332nd Group, which was made up of the 100th, 301st, and 302nd Squadrons had black officers. The all-black Army Air Command consisted of 400 enlisted men, 33 pilots and 27 airplanes. Those men were America’s first black military airmen, and most of them were high school and college graduates. Those Tuskegee Airmen performed well despite the racism and discrimination they experienced on a daily basis and gained an impressive record. They flew over 15,500 sorties and completed 1,598 missions in Africa, France, Italy, Poland, and Russia, escorting 200 heavy bombers deep into Germany. They accumulated 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, a Legion of Merit, a Silver Star, 14 Bronze Stars, and 744 Air Medals. It was not easy because at first many American white pilots refused to associate with them until the French and other foreign pilots asked the Tuskegee Airmen to escort and defend them on missions due to their outstanding battle records. Wilmore Leonard volunteered in 1941 and graduated from Tuskegee’s Army Airfield School’s Single Engine Section in Class SE-42-H on September 6, 1942. On that date, he earned his wings, was commissioned a Second Lieutenant, and was the first African American from the Eastern Shore to do so. He was a member of the 6th cadet graduation class and was one of the first 50 African American combat fighter pilots in American history. His squadron was the first to join the 332nd Fighter Group. Leonard also joined the 99th Squadron, a part of the 332nd Fighter Group, known as the “Red Tails,” flew bomber escort missions for the 15th Air Force, attacked enemy positions in support of ground forces, and engaged in air combat. During his active military career, Wilmore Leonard was stationed at Tuskegee, Alabama; Oscoda, Michigan; Camp Kilmer, New Jersey; and Selfridge Field, Michigan. He and other black officers were often discriminated against and were not given the same accommodations and privileges as White officers. Leonard, the other Tuskegee Airmen, and African American soldiers fought the Double V: fought for victory in Europe during the war and also fought for democracy at home when they returned to the United States, even though they were treated better in Europe and Germany than at home. For his meritorious duty as a Tuskegee Airman, Wilmore B. Leonard was awarded seven Battle Stars. In 1945, he acted as the head of the Department of Technical Inspection for the United States Army and retired from active military duty in 1946 with the rank of Captain. However, after the war ended, Wilmore Leonard remained in the Army Reserves and obtained the rank of Major. In 1947, Wilmore Leonard applied for and was provisionally admitted to the University of Maryland’s graduate school for a postgraduate course in chemistry. However, the university refused to admit Leonard, an ex-Army decorated officer, on the grounds that the formal notice in writing of his acceptance as a student had been “a mistake.” An investigation revealed that in 1947 Leonard was offered provisional enrollment, supposedly due to poor grades compared to other applicants. Further investigation also revealed that when all applications had been received, Wilmore Leonard and at least six other black candidates who sought admission to the graduate school were denied admission. The records revealed that the president of the university rejected Leonard’s application for admission, but it was Edgar F. Long, the head of admissions at the University of Maryland, who travelled to Leonard’s home in Salisbury, Maryland in an effort to force Leonard to turn over the printed card that granted him provisional admittance to the university. Leonard refused to return the card, at which point Long told Leonard to keep it as a souvenir because his admission had been “a mistake.” Long then offered Leonard a scholarship for out-of-state study, possibly out of fear that Leonard would sue the university and/or seek media support for his cause. A September 27, 1947 Chicago Defender newspaper article related Leonard’s case and the fact that the college cited dissatisfaction with his previous average grades as a ruse for having denied him admission instead of stating that it was possibly due to Leonard’s race. The same scenario was also cited in a Baltimore Afro-American newspaper article, dated August 16, 1947. Upon rejection of his admission to the University of Maryland, in 1948 Wilmore Leonard enrolled in Howard University’s School of Dentistry and earned the Doctor of Dental Surgery in 1952. He taught as a professor of dentistry for 25 years at Howard University (HU) until he retired in May of 1976. During that period, he served as Howard University’s Associate Director of Clinics, and was also Secretary to the Faculty. He taught oral diagnosis, endodontics, oral therapeutics, and pharmacology. Howard University’s School of Dentistry awarded him the HU College of Dentistry Alumni Award for outstanding contributions to dental education. He was a member of the American Dental Association, the National Dental Association, the Robert T. Freeman Dental Society and the District of Columbia Dental Society. He also authored multiple journal articles on periodontology and endodontics. He officially retired from dentistry in May of 1977. Local and family lore has stated that Dr. Wilmore B. Leonard used the money that was given to him by Edgar F. Long, the head of admissions at the University of Maryland, to open and establish Leonard’s dental office in Washington, D.C. Dr. Leonard had a distinguished career as a dental surgeon and as one of the 1007 documented Tuskegee Airmen. Dr. Wilmore Brown Leonard, a beloved dentist, professor, Tuskegee Airman and Eastern Shore and Salisbury, Maryland native died at the age of 61 from cancer on April 2, 1978 at Howard University Hospital in Washington, D.C. NOTE: There are at least eleven (11) other Tuskegee Airmen known to have been born, reared, worked and lived on Delmarva. Dr. Clara Small Professor Emeritus at Salisbury University

0 Comments

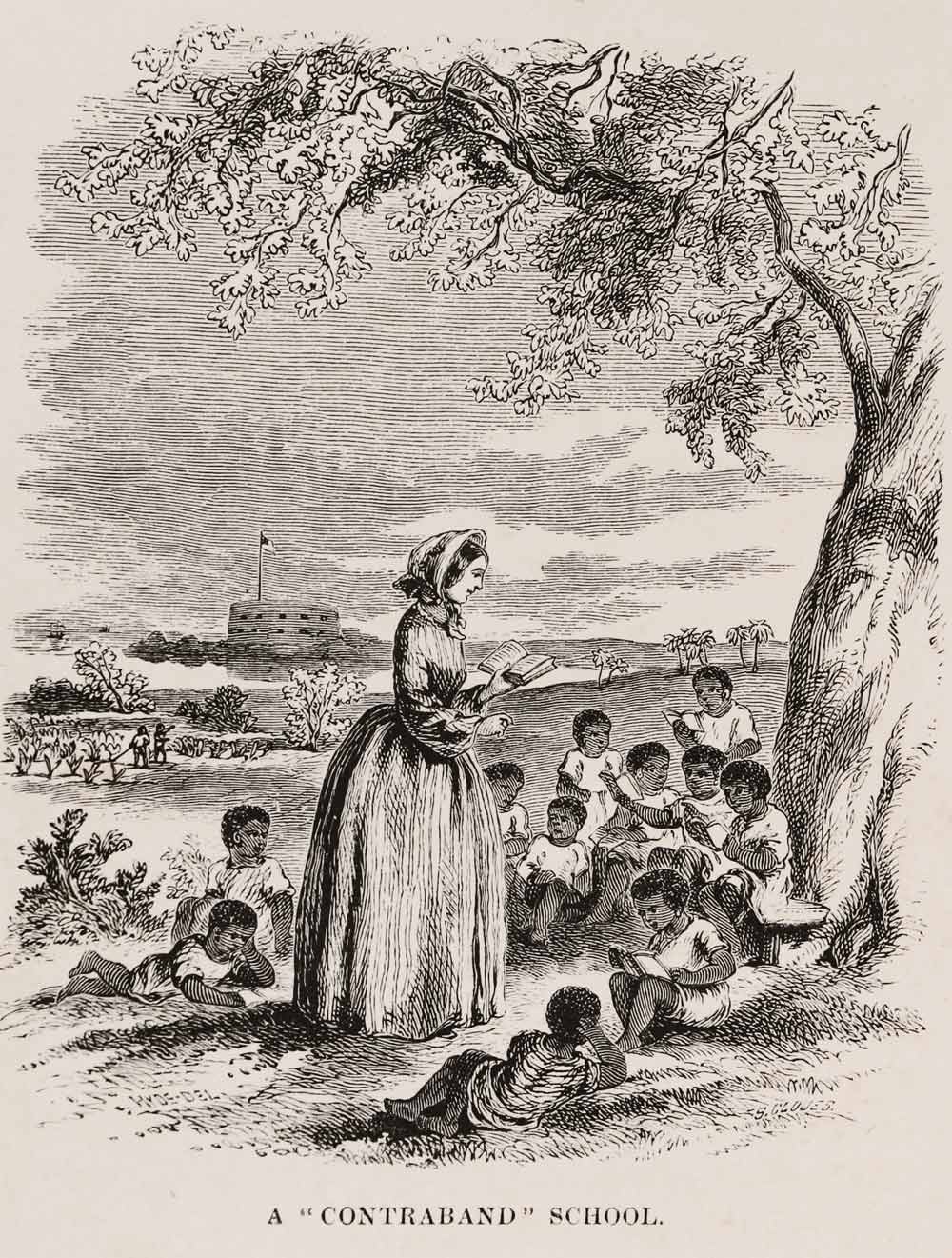

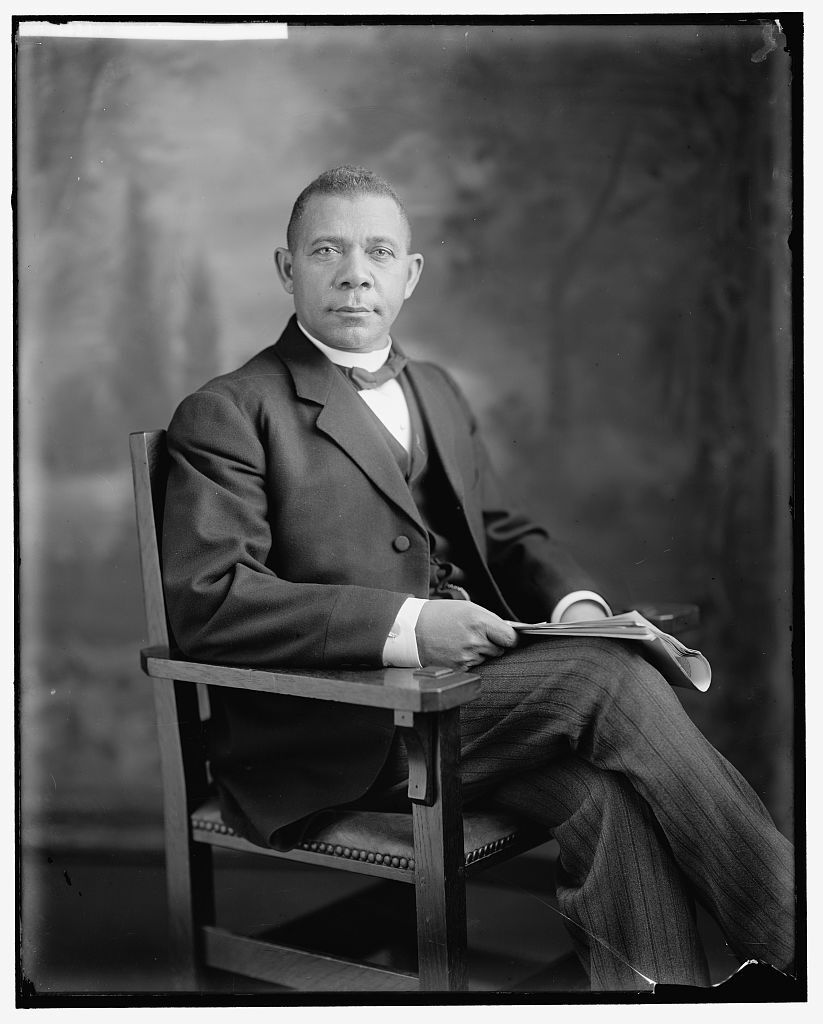

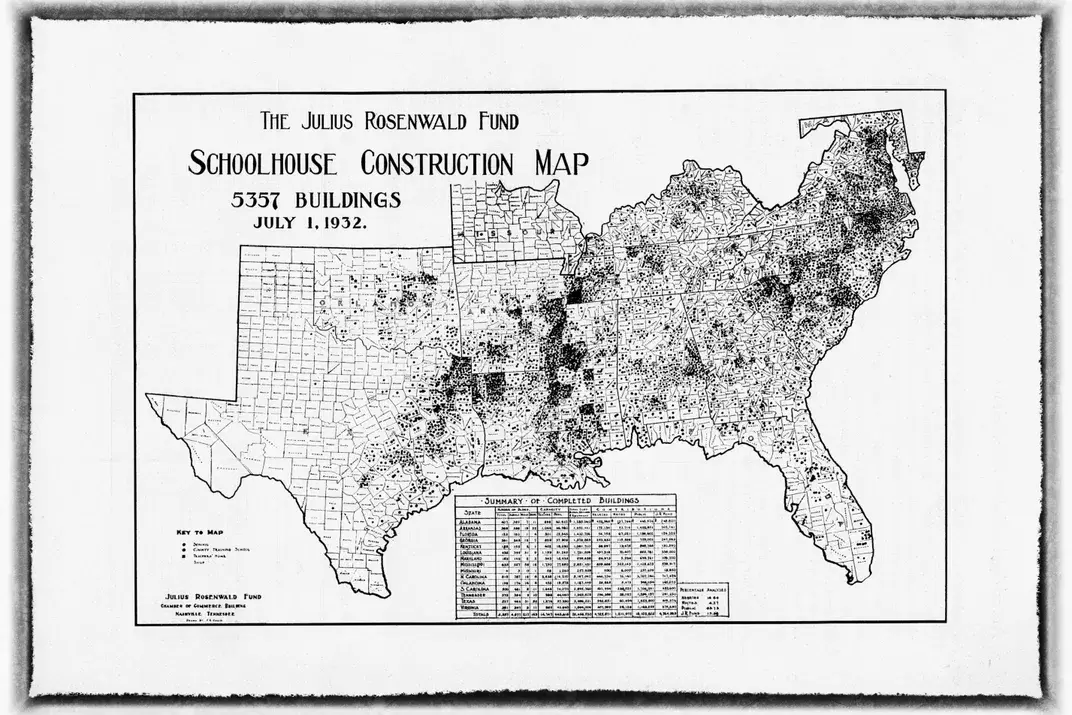

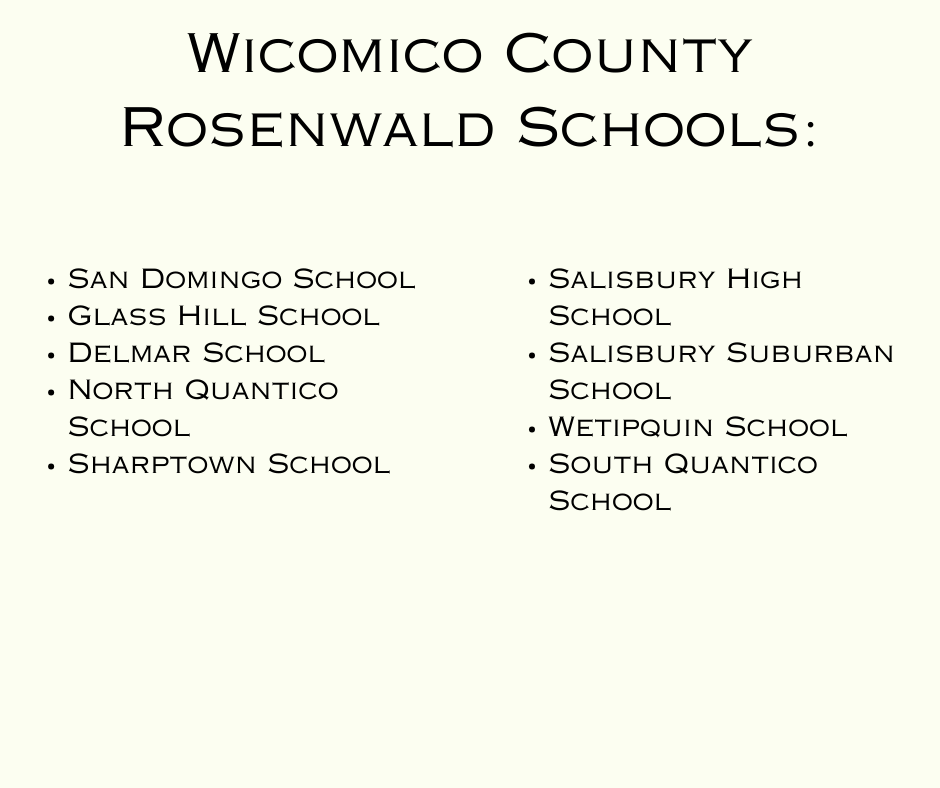

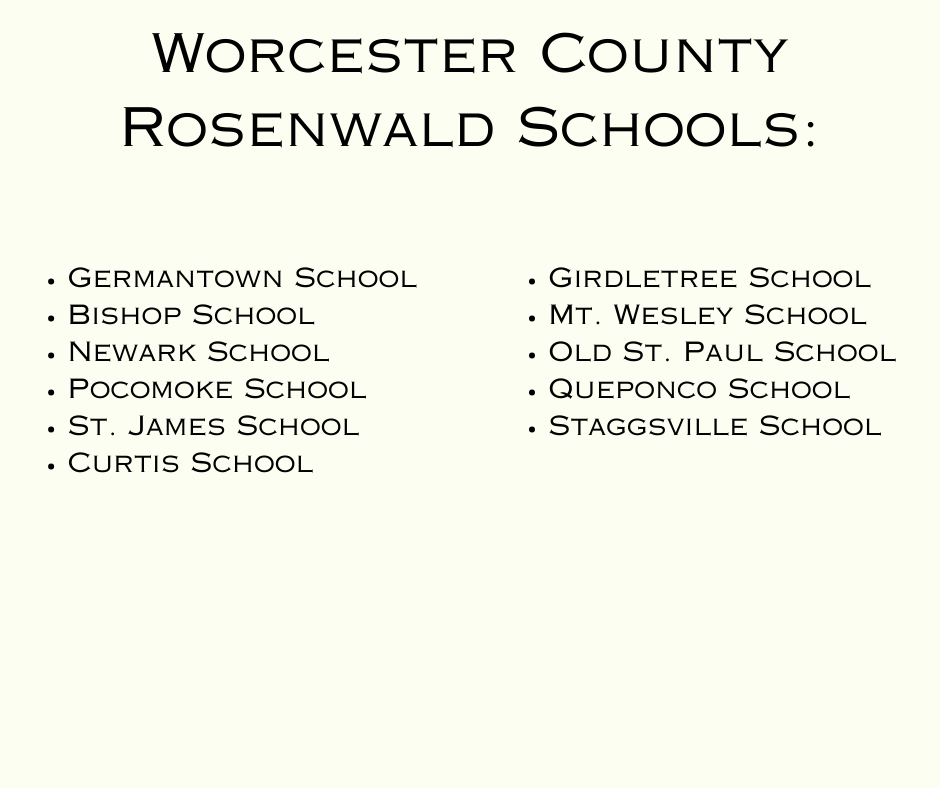

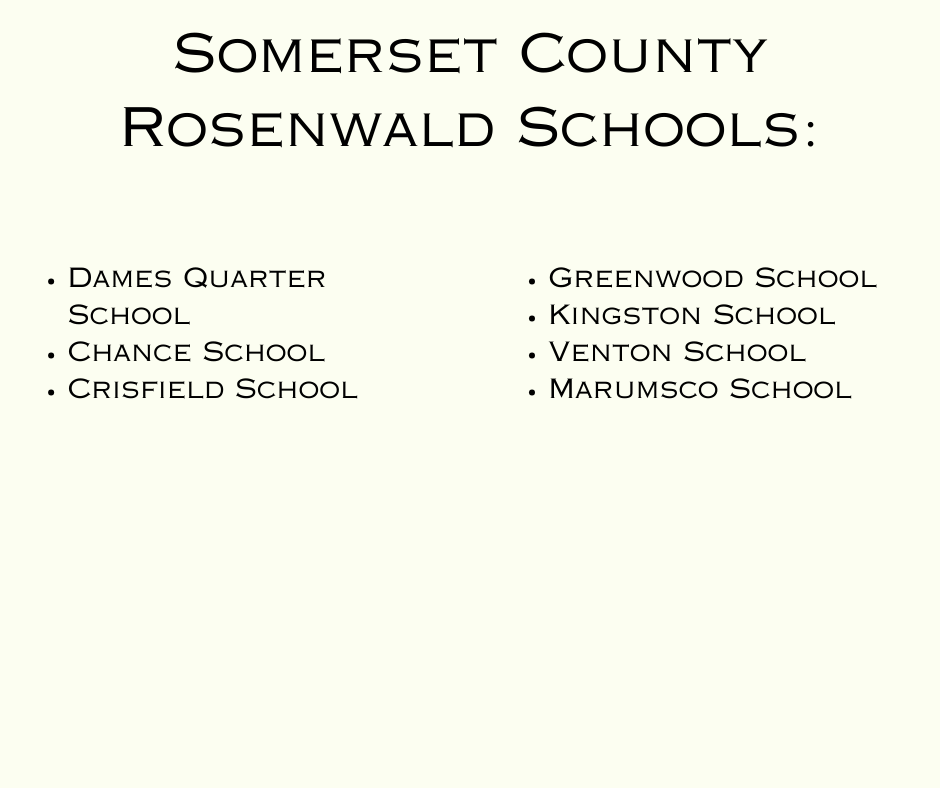

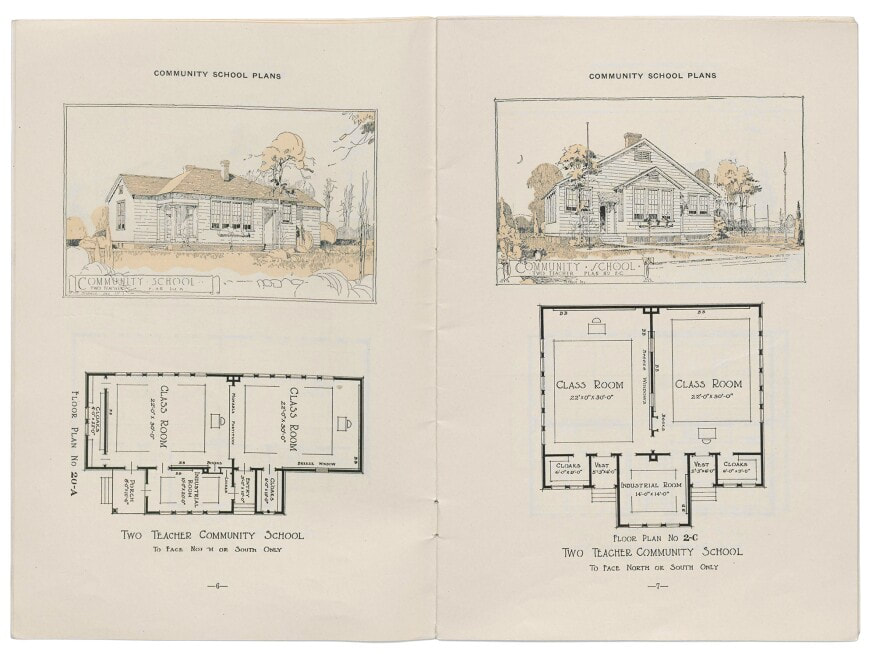

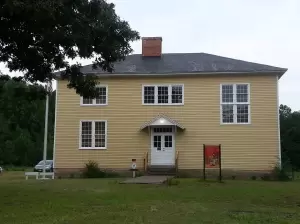

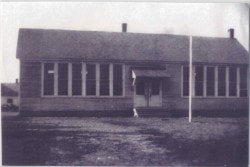

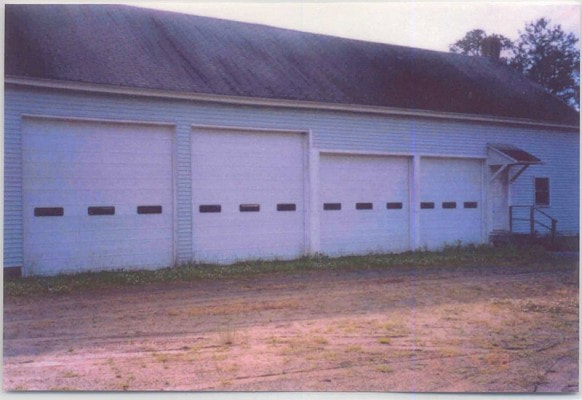

Education is something that many Americans take for granted today, but for some groups of people, especially Black Americans, education was much harder to come by. Black education throughout American history had been restricted in several ways, either by directly prohibiting it, as was the case before the Civil War and Reconstruction, or by finding ways to undermine it, such as through segregation during the Jim Crow Era. However, Black determination for an education led Black Americans to find ways around these restrictions. Rosenwald Schools were a product of this determination and helped facilitate Black education throughout the South, including on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Colored Scholars Excluded from Schools The John Hay Library, Brown University 1839 Black Education Before the 13th AmendmentPrior to the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865, many states had passed laws barring the enslaved from receiving an education. These laws became far more common following Nat Turner’s slave revolt in 1831 and even affected the education of free Black people. Education and literacy among the enslaved and free was deemed to be a threat to the institution of slavery. Literacy allowed slaves to question their standing in society, read abolitionist materials, and made it generally more difficult for slave owners to maintain control over the enslaved. In a way, literacy served as an avenue to freedom. Even after abolition and Reconstruction, Black education remained restricted through racial segregation to maintain the status quo of the racial hierarchy. Black schools were underfunded and too few to provide a solid education for Black children. However, one Black man’s ambitions for education soon changed this. Wartime Education American Antiquarian Society 1863 Booker T. Washington, Julius Rosenwald and the School Building ProgramBooker T. Washington (1856-1915) played a significant role in the world of Black education. Born as a slave on a Virginia plantation, Washington later worked in the salt industry in Malden, West Virginia, and then in the coal mines. In his autobiography Up From Slavery, he recalls an “intense longing to learn to read” as a child and made it his life goal to be able to read. Growing up, Washington found that opportunities for education were scarce and that the Black people that grew up in the coal mines tended to stagnate. Without an education and no knowledge of what life was like outside of the mines, they became trapped with no ambition to get out of the mines. Washington understood that receiving an education was the key to escaping this fate and left for the Hampton Normal School in 1872 with very few belongings and little money. Making the journey through a combination of hitch hiking and walking, Washington graduated from Hampton in 1875 and was greatly influenced by its principal Samuel Chapman Armstrong. Armstrong had advocated a particular kind of practical education: one that both elevates and installs character into African Americans. Washington applied this philosophy of self-help in the construction of Tuskegee Normal School after his appointment as principal by borrowing money to buy land and having students build the necessary materials. Booker T. Washington (1856-1915) Library of Congress 1905 In the early 20th Century, the state of Black education in the South remained poor. There were very few public schools and the ones that did exist lacked adequate facilities, supplies, and staff. In the early 20th century, Booker T. Washington had begun using money from various philanthropists to construct single room schoolhouses in the South and reached out to Julius Rosenwald in 1912. Washington proposed to build six schoolhouses with $600 each and using community labor with local materials to save on costs. The idea intrigued Rosenwald who put up $2,800. Julius Rosenwald Fisk University Loachapoka School, Alabama, the First Rosenwald School Sears Home Services Blog 1913 These six schoolhouses were deemed a success and motivated Rosenwald to continue funding future schools, which in turn helped garner the interest of Southern states in supporting Black education. What had started as a small initiative in Alabama soon spread throughout the South. In 1920 the school building program’s management was transferred to the Rosenwald Fund under the leadership of S.L. Smith who sent out standardized plans to interested Black leaders. By the end of the 1920s, there was a shift away from building single room schools as demand declined. In 1931 the goal of 5,000 schools was surpassed and Edwin Embree, who had taken control of the Fund in the late 1920s, suggested a halt to the school building program. Embree wanted the concentration of the Fund moved to maintaining and improving the quality of education in the schools and Rosenwald consented. The Julius Rosenwald Fund Schoolhouse Construction Map Fisk University 1932 Rosenwald Schools in Maryland and the Eastern ShoreMaryland had benefited greatly from the Rosenwald Fund in terms of Black education. It was not until 1872 that Maryland’s constitution required school districts to provide an education to Black children and even then, public funding was still insufficient. The Rosenwald Fund helped solve this problem, but the Fund and success still relied on funding from the state and community. As with other Rosenwald Schools, those in Maryland derived funding from three sources: public funding (state and county), the community, and the Rosenwald Fund. In most cases, public and community funding had to at least match what the Rosenwald Fund was providing. Another aspect of these schools was that many of these communities helped provide the materials, labor, and in most (if not all cases) the land, for these schools. These factors helped ensure that communities were invested in the success of the schools. The estimated number of Rosenwald Schools built in Maryland was 156 according to the Maryland Historical Trust with around 50 still standing. On the Lower Eastern Shore there were a total of 27 built. In Wicomico County there were nine Rosenwald Schools built. The San Domingo School continues standing as a unique example of a Rosenwald School in Mardela Springs. Originally called Sharptown Colored School, it was built in 1919 following a petition by San Domingo’s Black community for a school. However, their petition stood out from the others as they were willing to donate nearly all the necessary materials. Residents donated two acres of land, were willing to cut and deliver the lumber, willing to excavate the basement, and were willing to raise money for the materials. Seeing this offer, the Wicomico Board of Education decided to plan a four-room school, allocating $3,500 for the school. The community put up $800 while the Rosenwald Fund provided $500. San Domingo School was unique in that it deviated from the typical Rosenwald design. Most schools were designed to be single-story with few corridors to maximize space and save on costs. Buildings also had to face east-west to efficiently make use of sunlight due to the lack of rural electricity. These guidelines were strictly enforced, and variations required approval by an administrator. San Domingo, on the other hand, was a two-story school, but still had an efficient plan. Folding doors gave the interior space flexibility, allowing rooms to be divided and combined as needed. Additionally, large windows, like with all Rosenwald Schools, provided natural lighting to the interior. Community School Plans from a 1924 Rosenwald Fund Bulletin The Journal of the American Institute of Architects 1924 San Domingo School operated from 1919 until 1961 when it was sold by the Board of Education to the Trustees of the Sharptown Recreation and Lodge Center who remodeled the building as a lodge and community center. In the 2000s there was an effort led by Newell Quinton, a former student at the school, to restore the school using $200,000 raised through grants and community donations. By 2014, San Domingo was opened as a community center and recreation of the original school. San Domingo Community and Cultural Center Delmarva African American History 2014 Worcester County saw a total of eleven Rosenwald Schools built. In Berlin, the Germantown School follows a more traditional Rosenwald building plan. Germantown School is a single story two-room classroom with large windows on its east and west side to maximize the use of sunlight. Also, like other Rosenwald Schools, Germantown was built through community initiative. In 1922 Isaac B. Henry and Mary L. Henry sold two acres to the Board of Education for $10 to be used for the construction of a school. The community also raised the necessary funds to match those of the Rosenwald Fund and the county. Having the land, money, and labor at hand accelerated the approval process and allowed the school to be built and opened the following year. Original Germantown School Germantown School Community Heritage Center c.1920s-1950s Germantown School Community Heritage Center 2023 Germantown School remained in service until the desegregation of schools in the 1950s at which point it was turned into a garage for Worcester County. However, in the 1990s, community interest led to a movement to reclaim the school from the County. Much like San Domingo, this effort was led by a former student, Joseph Purnell. In the early 2000s the deed was restored and in 2005 it was estimated that $250,000 was needed for the restoration of Germantown School. A good amount of this budget was provided through grants, but like the original construction, much was provided by community donations and fundraising. In 2010 the Germantown School had its groundbreaking, marking the beginning of a three-year restoration process. The school now serves its original purpose again: bringing the community together through events, lectures, and exhibits. Germantown School Turned into a County Garage Germantown School Community Heritage Center c.1960-2000 Germantown School Classroom Recreation Germantown School Community Heritage Center 2023 In Somerset County there were seven Rosenwald Schools. These again were a product of Black investment and interest in education. As of the publishing of this article, no Rosenwald School has been restored as San Domingo or Germantown schools were. Most are in poor condition, but newspaper articles reflect the effort put in by Black communities to have these schools built. One 1930 edition of the Marylander and Herald mentions the building of the Greenwood School, a two-room Rosenwald School, as part of the Rosenwald Plan. According to this, the school was to be built next to the existing school and work was to begin immediately. Another edition of the Marylander and Herald, this time from 1951, describes maintenance done on Black schools, including Rosenwald Schools, and the amounts spent on each. Greenwood had running water installed as well along with two additional partitions. Superintendent C. Allen commented on these improvements, writing that parent teacher associations played a major role in these repairs by providing much of the labor and materials needed. This continued support of the schools by the community years after their construction reflects the dedication of Black communities to the education of their youth as well as the success of the Rosenwald program in keeping the community invested in the long-term success of these schools. Front View of the Former Dames Quarter School Photo by Karen Prengaman 2023 Interior of Abandoned Dames Quarter School Photo by Karen Prengaman 2023 While Rosenwald Schools were often criticized for their promotion of a practical or vocational education, they still contributed greatly to the education of Black Americans in the early 20th century not only by directly providing an education, but also by getting state governments to care about Black education. The initial success of the Rosenwald funded schools encouraged public funding to be used for Black education in Alabama and this pattern soon spread throughout the South. Additionally, until Brown V. Board of Education resulted in the beginning of the desegregation of schools, these Rosenwald Schools were often the only source of education for rural Black communities and provided an education that the students’ forebears did not have access to. This striving for an education also served as a form of Black resistance as it was a way for Black Americans to empower themselves and undermine the restrictions of the Jim Crow Era that were meant to keep the Black population suppressed.

Andre Nieto Jaime B.A. History |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed