|

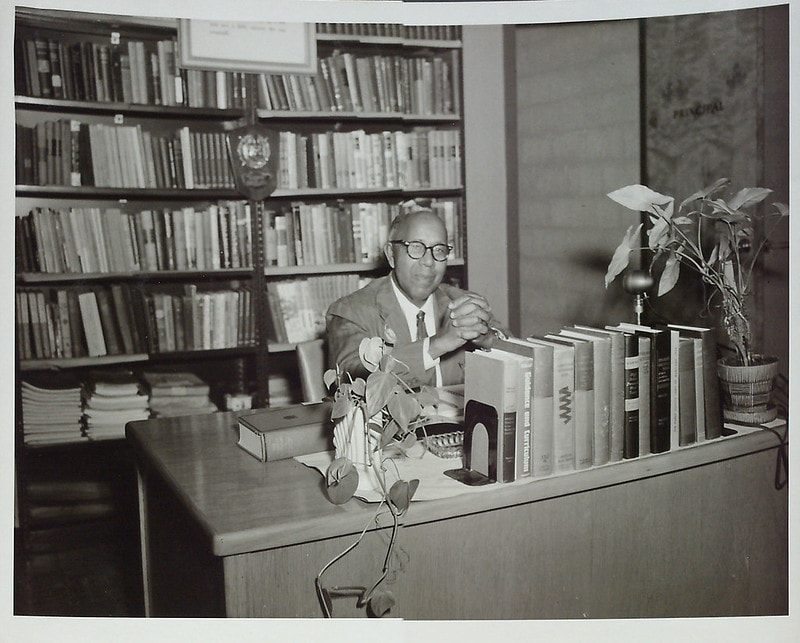

Article by Dr. Clara Small Orrensy William Hull (1919 - 2013) Orrensy William Hull, Jr., also called “William,” was born November 2, 1919 to the late Lottie Conway Hull and Orrensy William Hull, Sr., in Wetipquin, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. The oldest son and the second-born of nine children, Orrensy grew up on his parent’s farm and spent much of his time growing and trucking produce to markets in the Baltimore and Washington, D.C. areas. William’s early education was in a three-room school building in Nanticoke, Maryland, where he finished second in his class from Nanticoke High School. Upon graduation from high school, William matriculated to Lincoln University, in Lincoln University, Pennsylvania, the school he later credited as helping “to make him the man that he became.” At Lincoln University, he served as manager of the track team, and also pledged Phi Beta Sigma, a service fraternity in which his membership spanned over 75 years. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in Physics with a minor in Chemistry from Lincoln. He later obtained a Master of Arts degree in Secondary Education from the University of Pennsylvania. William Hull also received a Master of Science degree in Physics and an Electrical Engineering Equivalency degree from the Stevens Institute of Technology and a Ph.D. equivalency in Physics from the University of Pennsylvania. His career goals and thirst for knowledge were interrupted when he was drafted and served in the United States Army during World War II. He served as a Signal Supply Officer, while stationed overseas in Italy. Classified as a Tech 4 (Technician 4), he received an Army Commendation for his work with the 92nd Infantry Division, and he was honorably discharged in 1946. Upon the completion of his military obligations and discharge from service, William began his career as a lifelong educator. From 1946 to 1962, William served as a teacher and Vice Principal at Salisbury High School. He was appointed by Governor Spiro Agnew to the Wicomico County Board of Education and served from 1966 to 1971. He also became the first African American who served in that position in Wicomico County. Upon the resignation of another board member, Orrensy became Vice President of the Board. At the time of his appointment in 1967, the Board of Education consisted of one African American, one woman and three Democrats and three Republicans. Salisbury High School Exterior Linda Duyer African-American History Collection (2012.021) Nabb Research Center Mr. Hull was an advocate for better schools, equality education, and training for all children, and, as such, served on numerous committees. One of those committees was the Vocational Advisory Council which was established to analyze the Wicomico County’s vocational program, to examine its strengths and weaknesses, and to advise the board. He also noted that there were few African Americans on the council and suggested that there should be others. After the completion of his term on the board on June 30, 1970, the Board of Education on July 14, 1971, commended Mr. Hull for his service, but he was not reappointed to another term. After twenty-one years of service in secondary education, William Hull turned his passion for educating others to higher education. He spent over 21 years of service from 1960 -1982 as a professor at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES). He was also a faculty member at Salisbury State College, now Salisbury University, from 1968-1970, and was the first African American professor to teach at the college. In 1975, as an Associate Professor of Physics, he received awards for distinguished service to the University (UMES), including the title he loved, “Most Helpful Teacher,” which was based on votes from students and staff. He was also recognized for his teaching ability by then President Dr. William P. Hytche. During his tenure at Old Maryland State (UMES), Mr. Hull also served as the Advisor to the Cooperative Education Program. He taught several generations of families and was frequently invited to attend class reunions of his former students. Upon his retirement on May 16, 1982, he was awarded the title of Associate Professor Emeritus by the University of Maryland Board of Regents. Mr. Hull was a strong supporter of UMES’ efforts to raise funds for program development and scholarships important to the perpetuation of academic excellence. After retirement from UMES, he continued to serve on the university’s fundraising campaigns. Postcard of Maryland State College's "Dormitory for Women" University of Maryland Eastern Shore c. mid-1950s Trigg Hall, Maryland State College Post Card c.1940s-1960s HipPostcard Mr. Hull was also very much involved in the civic activities of the local community. Some of those activities included the following:

Mr. Hull was committed to education, his family, and his community. He was very aware of racism and discrimination on Delmarva, and he was determined to find ways to lessen the sting. He found ways to help create opportunities for African Americans to receive a good education and he actively advocated for underserved residents of the community and made the entire community better for everyone. An example of his beliefs began in the 1940’s, when he began selling cars part-time with Oliphant Chevrolet to help put automobile purchases within reach for area African American families. His affiliation with the local Chevrolet dealer, as an esteemed consultant and salesman, continued for many years as a member of the Courtesy Chevrolet family of dealerships. Oliphant Chevrolet Advertisement The Daily Times, 1968 Newspapers.com Mr. Hull was also very active in a couple of service organizations for which he was exceptionally proud. He was a member of Phi Beta Sigma Fraternity and in January of 2013, he was honored with the Living Legacy Award for 75 years of service to his fraternity. He was a charter member and founder of the local Delta Gamma Sigma Chapter, in which he held many positions and mentored many of its younger members. A second fraternity in which he was also a founder and charter member was Gamma Theta Chapter of the Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity, Inc., which is the oldest Greek organization among African Americans. Due to his leadership, service, and scholarship, the fraternity established in his honor the O. William Hull Boule Scholarship Program, a scholarship and mentoring program for young men on Delmarva.

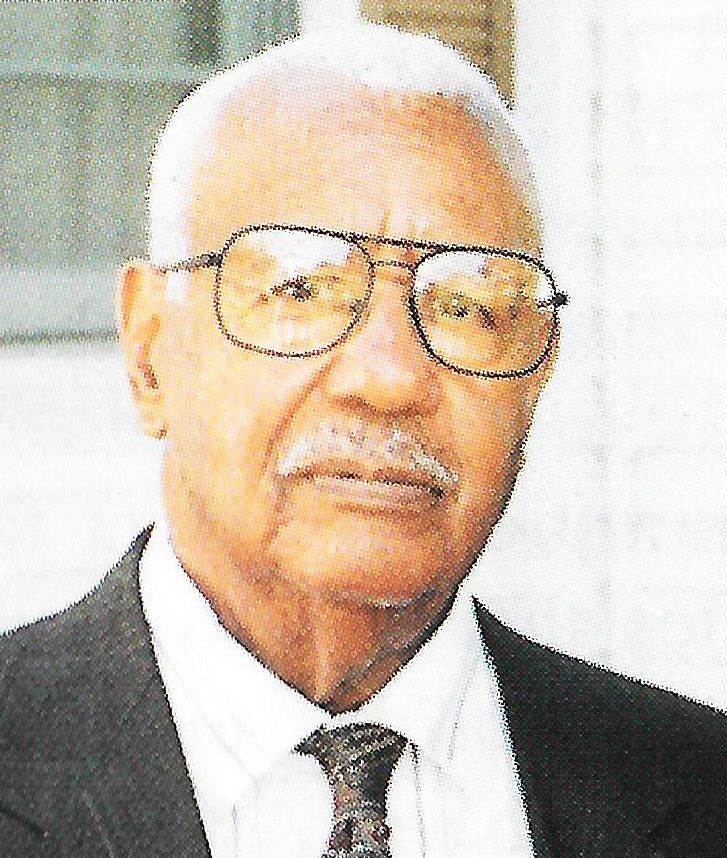

Mr. Hull’s passion for teaching and learning carried over into his leisure time and retirement years. He learned to swim at the age of 65, golf at the age of 75, and he was well aware of local and world affairs throughout his lifetime. His hobbies included gardening (the fruits of his labor which he shared with family and friends), photography, golfing, and vacationing with his family throughout the United States, Canada, Mexico, France, Italy and Monaco. Mr. Orrensy William Hull, Jr., was a highly respected, very active member of the community and his church, Wesley Temple United Methodist Church in Salisbury, Maryland, in which he served on numerous committees, until his health declined. He passed into eternal rest on November 26, 2013 and his celebration of life services were held at Wesley Temple on December 7, 2013. His interment was at the Eastern Shore Veteran’s Cemetery, Hurlock, Maryland. Mr. Hull is remembered as a lifelong learner who never lost his thirst for knowledge, and he encouraged others to do the same. One of the lasting examples of his legacy is the Wicomico Nursing Home on Booth Street, which showed his concern for others, especially for the African American community. His hope for the betterment of the entire community and commitment to others was possibly the force which compelled him to strive for excellence and encouraged others to do the same.

0 Comments

Article by Andre Nieto Jaime Donzelle and Melvin Hutt in an issue of The Baltimore Afro-American The Baltimore Afro-American 1957 Salisbury’s Mainlake Building, first built in 1930, has housed several businesses over the 94 years it has been standing at the corner of West Main and Lake streets. This building sat at the heart of what was once a bustling Black business district containing theaters, clubs, restaurants, service stations, and more. While there was some crossing of the color line, this was for the most part, a Black entertainment district. Nearly 70 years ago, the Franklin Hotel was part of that thriving community. Originally opened in 1955 by Melvin Clifton Hutt, a born and raised Salisbury local, the Franklin Hotel contributed to this robust district in Wester Salisbury and represented a step towards integration by opening with the intention of serving all people regardless of color in an era where segregation was the norm. Mainlake Building University of Virginia Mainlake Building in the 1980s Office of Publication Photographs SUA-031 c. 1982-1983 Melvin C. Hutt (1921 – 1986) was the eldest son of Harrison and Ella Hutt. Melvin Hutt, judging from census records and newspapers, spent most of his life in Salisbury, living within the city in both the 1930 census as well as the 1950 census. However, he appears to be absent from the 1940 census along with his father. However, his mother and his siblings are recorded in the 1940 census in Fruitland living with Ella Hutt’s 60-year-old parents Ross and Ida Harmon. Melvin’s draft registration and military records provide some insight into his young adult life. Hutt registered for the military draft in February of 1942 and his registration lists him as living on Route 4 in Salisbury, the same address he lists for Ella Hutt. The same document also reveals that he is working for Maurice Sadick, a Polish immigrant who owned and operated Eastern Shore News in Salisbury. A month later, Hutt’s name was drawn in a draft lottery. His enlistment record confirms that he was a newsboy and shows his education level as “grammar school” and that his service was to last the duration of the war, plus six months afterward. Melvin Clifton Hutt's Military Draft Card FamilySearch 1942 When Melvin Hutt returned from his service, he married Addie Donzelle Fant (1921 – 1970) from South Carolina in 1946. At the time of his marriage, Hutt had been living on 510 East Church Street, but a few years later in 1951, Hutt purchased a home on 219 East Church Street for $8,000. Addie, usually referred to as Donzelle, came to live in Salisbury with Hutt and became a teacher in Somerset and then Wicomico County. Having a background in education after attending Temple University and Bowie State Teachers College, she began a teaching career in Wicomico County. Donzelle spent a considerable amount of time tending to special education needs in the county and helped special education children secure job training for full-time employment after graduation. After teaching for twelve years, Donzelle was assigned to be the assistant supervisor of special education at the State Board of Education. A year after Hutt’s marriage to Donzelle, he opened the Veterans Service Station alongside David G. Jones on Lake and Gordon Street. Hutt and Jones extensively advertised their service station in newspapers such as The Salisbury Times and while some troubles did arise, such as a break in in 1952, the station seemed to be a successful business in the district. At some point, Hutt appears to have stated his own service station, as noted by an advertisement for a Texaco Station operated by Hutt on Main and Fitzwater Street in 1954. Hutt’s Texaco likewise appeared in several newspaper ads, including one in 1960 promoting the free Texaco Fire Chief Hats for children. Hutt’s service station was involved with the surrounding community and participated in a series of talks on community helpers with Salisbury Elementary School in 1958. Besides his service station, Melvin Hutt is also remembered for opening the Franklin Hotel, an important step towards integration in Salisbury. The hotel, named after Donzelle’s father Benjamin Franklin Fant, was opened on June 12th, 1955 in the Mainlake Building when the Black business and entertainment district was reaching its climax. Boasting 23 rooms equipped with modern amenities such as air conditioning, TVs, radios, telephones, tiled floors, carpeted halls, and 24 hour service, Hutt took great pride in the Franklin Hotel and saw it as a symbol of integration, stating that “we worked together, lived together, played together, men who were black, brown, yellow, and white, and we soon found there need be no trouble if you make up your mind about it.” While it is often referred to as a “hotel for negroes” or a hotel catering specifically towards Black patrons, Hutt makes it apparent that it was a hotel for everyone. Others also looked towards the Franklin Hotel with hopeful eyes. A 1957 article from The Baltimore Afro-American by Elizabeth Oliver begins by recalling the lynching of Matthew Williams in the courthouse lawn only 26 years earlier, but then transitions to the present, stating that “Today, it’s a different story” where there is now peace and intermingling between races in Salisbury. Oliver uses the Franklin Hotel as proof that times have changed and suggests that the opening of this hotel is a stride towards integrating society. Additionally, the Franklin Hotel appeared in the The Negro Travelers' Green Book, a guidebook listing locations nationwide that served African Americans, from 1956 to 1964 as a safe place for Black travelers to seek lodging. Franklin Hotel Listed in the 1956 Green Book The New York Public Library Digital Collections 1956 Hutt continued to operate the Franklin Hotel through the late 1950s and early 1960s, with some incidents like a small fire in the boiler room, a federal narcotics investigation, rowdy patrons, and declining business in the district posing challenges. Despite these hiccups, Hutt continued to operate the hotel, even opening the Franklin Hotel Beverage Store selling an assortment of alcohol in 1966. That same year, Hutt married Florine Victoria Hall at the Mt. Zion Methodist Church in Laurel, Maryland, seemingly having parted ways with Donzelle. A few years later, Melvin Hutt began operating the Miami Hotel in North Salisbury. In 1969, a notice in The Daily Times informed readers of Hutt’s application for a permit to operate the Miami Motel on 1804 North Salisbury Boulevard. This move was likely prompted by the decline of the business district owing to several factors, one of which was the construction and opening of the Salisbury Mall in October of 1968 and police harassment of residents. Hutt operated the Miami Motel until he passed from an apparent heart attack on Christmas day, 1986 while at Peninsula General Hospital. Miami Motel - Salisbury, Maryland The Cardboard America Motel Archive Salisbury MD Miami Motel Antiques Shop US Maryland Vintage Postcard Melvin C. Hutt Funeral Service The Daily Times December 28, 1986 While Melvin Hutt is remembered for his business endeavors such as his Texaco station and the Miami Motel, the Franklin Hotel was his most influential. It was one of the few locations, if not only locations, that provided boarding to Salisbury visitors without regard to race prior to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The hotel was so memorable that the City of Salisbury made efforts to preserve the building as the last vestige of a once flourishing Black business district. When Hutt moved on to his next venture, the Miami Motel, Larmar Corp. sold the building to Earl Church in 1972. After Church’s death in 1985 the city bought the property from Church’s widow, Gladys, to have greater control over redevelopment of the area before deciding to sell the property. However, before putting the Mainlake Building back on the market, Salisbury imposed restrictions to preserve the building for generations to come. A building once constructed to house white only businesses was turned into a space open to all people regardless of their color by Melvin Clifton Hutt. It is this dream that this building has been remembered by. References:

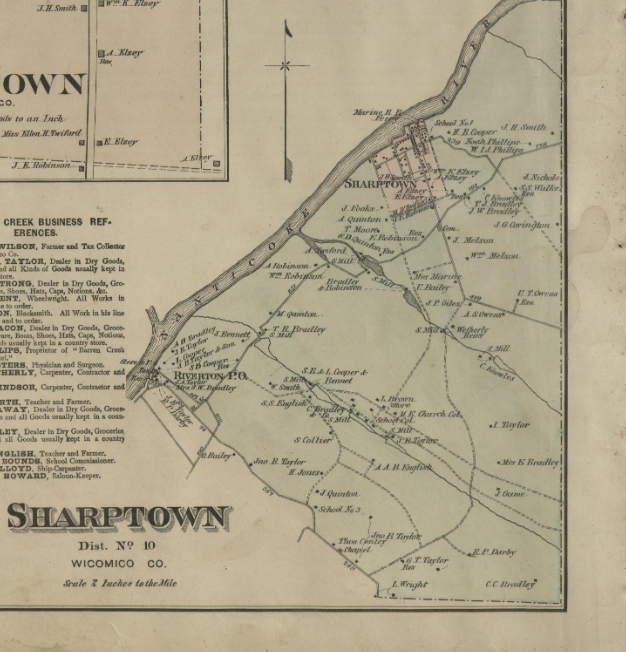

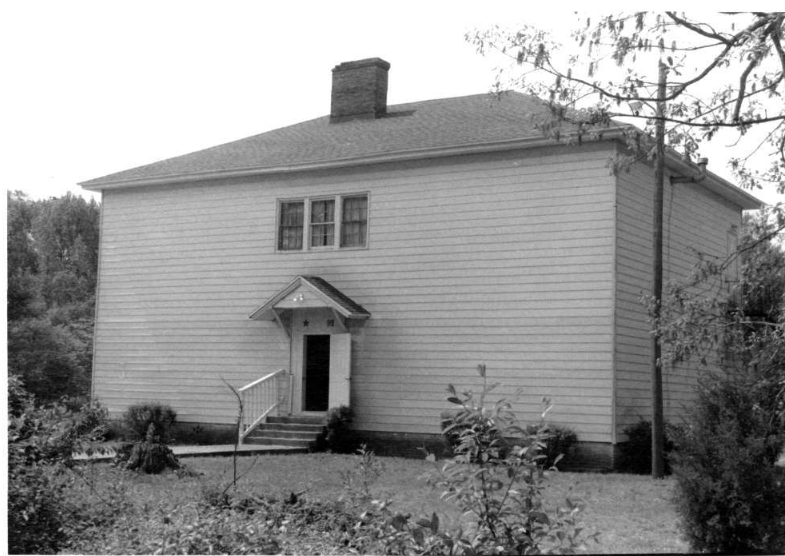

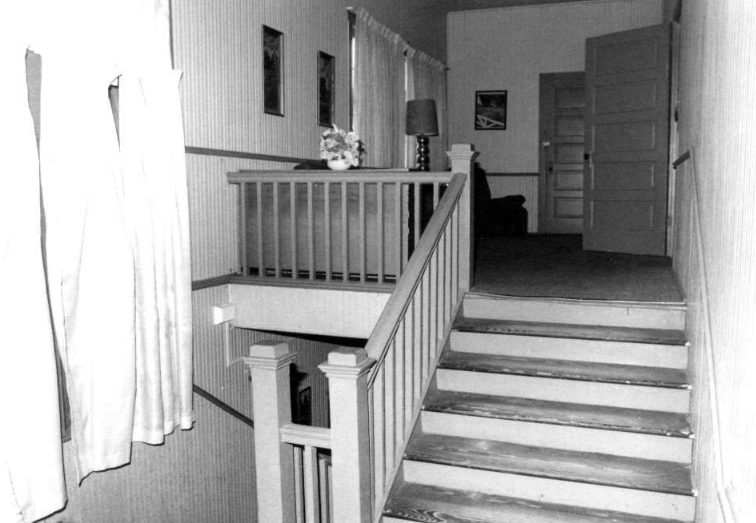

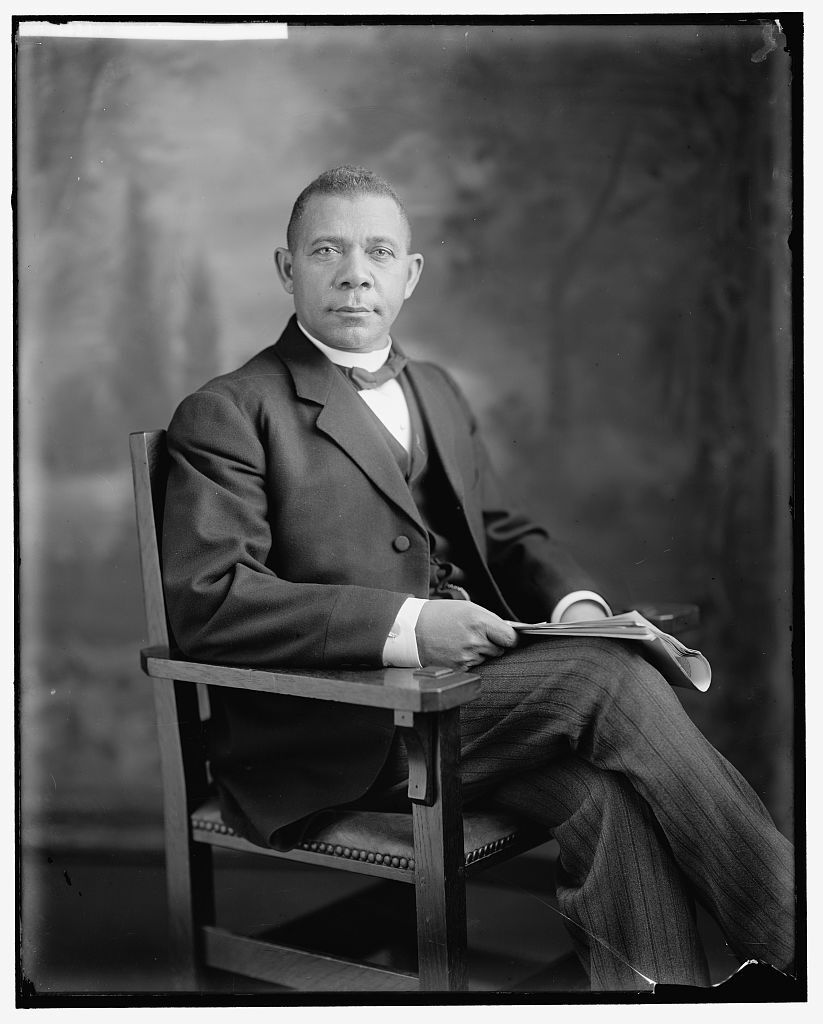

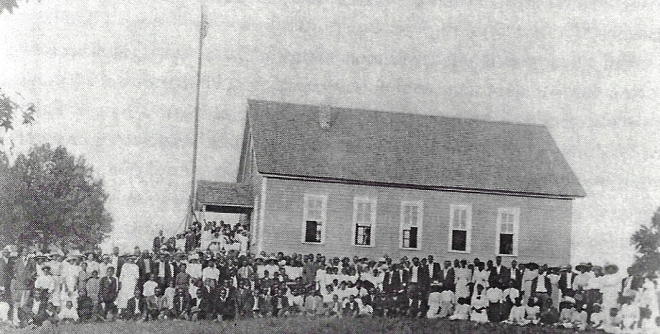

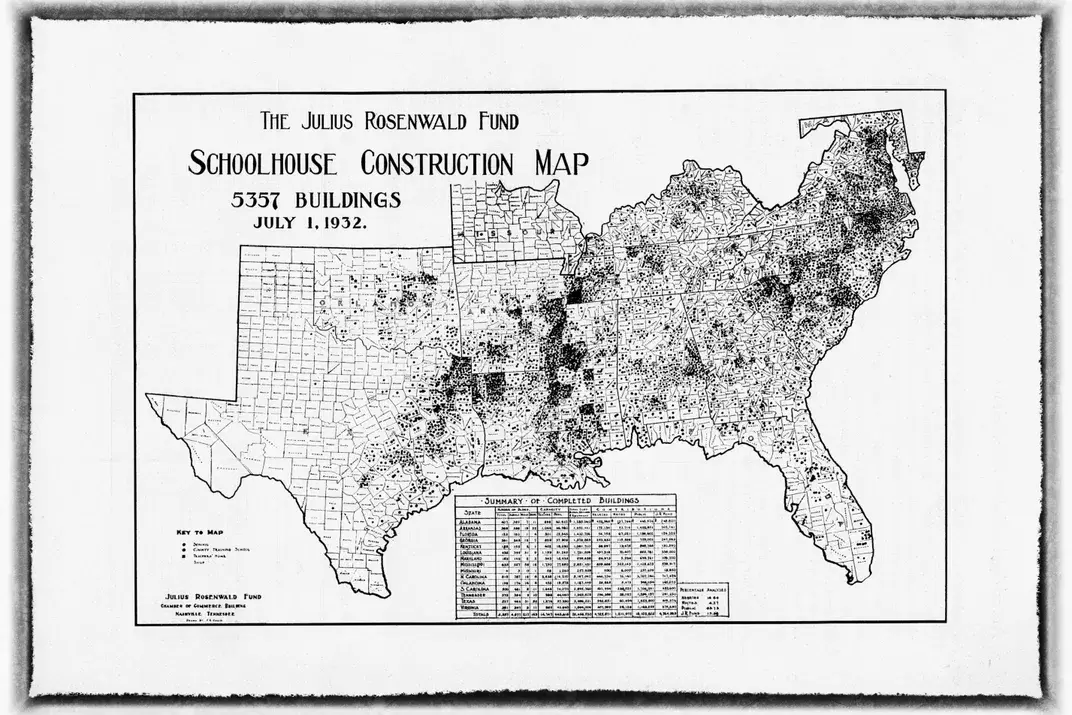

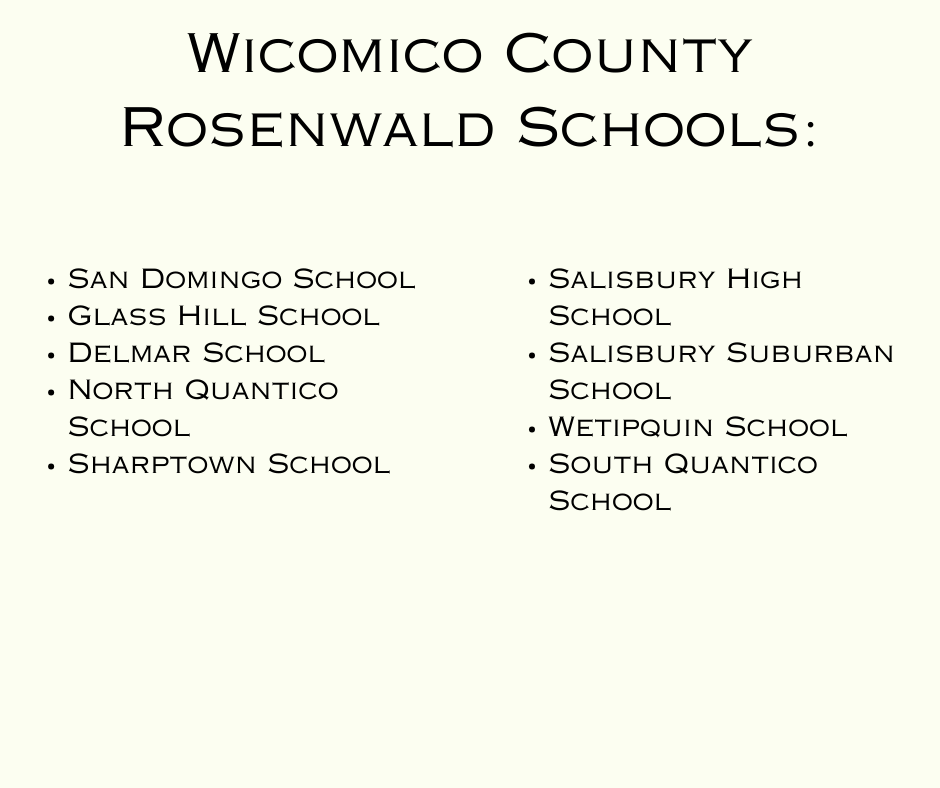

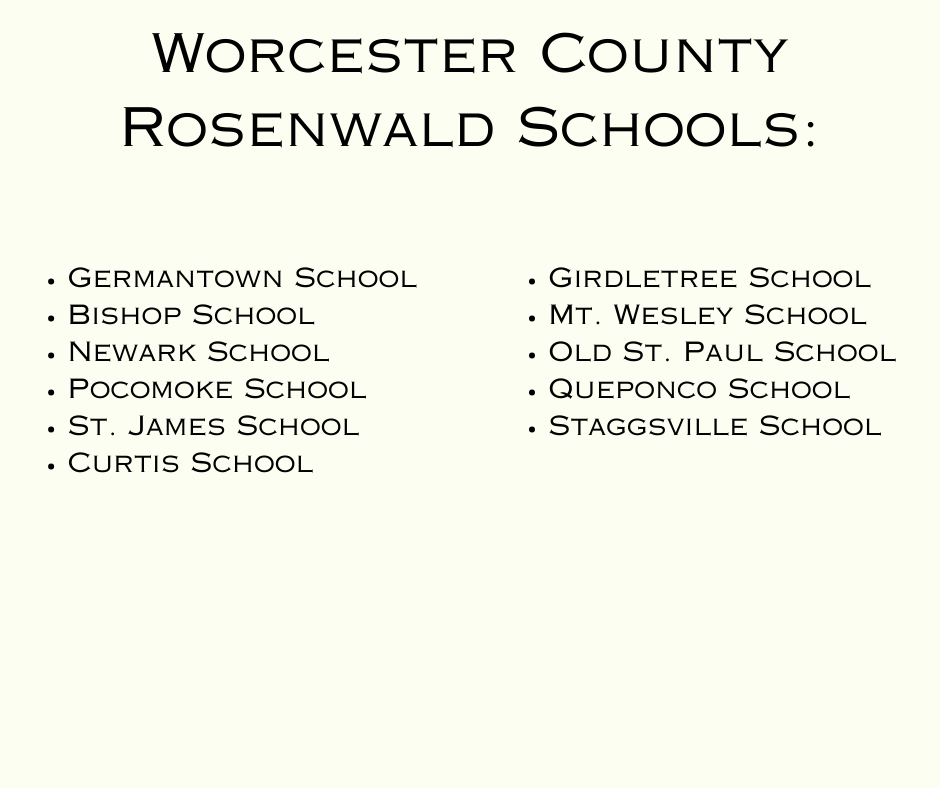

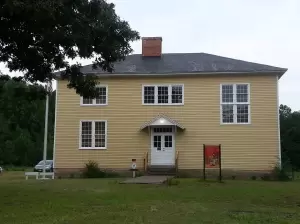

Primary Sources: “Director.” The Salisbury Times, June 10, 1954. “Florine Victoria Hutt, Melvin C. Hutt Are Wed.” The Daily Times, August 24, 1966. “Guns Stolen in Bureau’s Store: Loss Estimated at $300 by Manager.” The Salisbury Times, March 28th 1952. “Hotel Franklin Opens In Md. on Mixed Basis.” The Pittsburgh Courier / The Baltimore Afro-American, 1955. “Jury Awards $20,000 for Road Property.” The Salisbury Times, January 21, 1959. “Narcotics.” The Salisbury Times, October 1, 1960. “New! Just Open Franklin Hotel Beverage Store.” The Daily Times, July 14, 1966. “Notice.” The Daily Times, June 1st, 1969. “Make the Youngsters Happy with the New Texaco Fire-Chief Hat.” The Salisbury Times, August 5th 1960. "Maryland, World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1940-1945", , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:Q29H-JXNP : Thu Mar 07 14:28:34 UTC 2024), Entry for Melvin Clifton Hutt and Ella Hutt, 1942. "Melvin C. Hutt." The Daily Times, December 28, 1986. Oliver, Elizabeth. “There’s A Small Hotel.” Afro-American, August 10, 1957. Pirnazar, Zhila. “Donzelle & Melvin Hutt.” Archive for Racial & Cultural Healing Exhibit. Charles H. Chipman Cultural Center. June 18, 2023. https://www.chipmancenter.org/residents/donzelle-and-melvin-hutt “Policemen Help Put Out Fire Here.” The Salisbury Times, March 1, 1957. “$75,000 Hotel for Negroes to Open Here.” The Salisbury Times, June 11, 1955. “School Group Hears Service Station Man.” The Salisbury Times, March 31, 1958. “Teacher Here Given State School Post.” The Daily Times, July 14, 1967. “These Advertisers Wish You & Yours A Very Merry Christmas.” The Salisbury Times, December 24th, 1954. "United States Census, 1930", , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:X3H3-XP2 : Sat Mar 09 09:07:41 UTC 2024), Entry for Harrison Hutt and Ella Hutt, 1930. "United States Census, 1940", , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K7FY-32K : Sat Mar 09 00:46:50 UTC 2024), Entry for Ross Harmon and Ida Harmon, 1940. "United States Census, 1950", , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:6F96-ZHLQ : Tue Oct 03 09:34:19 UTC 2023), Entry for Melvin C Hutt and Donzelle F Hutt, 19 April 1950. "United States World War II Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946," database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:K8TM-JZ5 : 5 December 2014), Melvin C Hutt, enlisted 20 Jun 1942, Baltimore, Maryland, United States; citing "Electronic Army Serial Number Merged File, ca. 1938-1946," database, The National Archives: Access to Archival Databases (AAD) (http://aad.archives.gov : National Archives and Records Administration, 2002); NARA NAID 1263923, National Archives at College Park, Maryland. "Washington, Naturalization Records, 1850-1994", , FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QGPL-Q8LK : Mon Apr 29 18:56:33 UTC 2024), Entry for Moisha Or Maurice Sadick and Cecile, 1935. “Wicomico Names Drawn in Draft Lottery.” The Salisbury Times, March 19, 1942. “Youth Arrested on Disorderly Charge.” The Daily Times, September 8, 1967. Secondary: “Franklin Hotel,” The Architecture of The Negro Travelers' Green Book, University of Virginia, accessed June 3, 2024. https://community.village.virginia.edu/greenbooks/content/franklin-hotel Ian Post on behalf of Edward H. Nabb Research Center for Delmarva History and Culture. "The Entertainment District." Clio: Your Guide to History. January 24, 2022. Accessed June 10, 2024. https://theclio.com/entry/142091 Article by Dr. Clara Small Newell E. Quinton (1944 - ) Newell Emerson Quinton was born in 1944 to Mary Louise Stanley Quinton and George Bernard Quinton in San Domingo, Maryland. San Domingo, located between Mardela Springs and Sharptown, Maryland, is a rural, isolated, small community situated in northeastern Wicomico County. San Domingo was created by free African Americans in the early 19th century and Newell is a 5th generation descendant of the earliest settlers. Map of Sharptown from the 1877 Atlas of Somerset, Wicomico and Worcester Counties San Domingo can be seen south of Sharptown 1877 Atlas of Somerset, Wicomico, and Worcester Counties Internet Archive Newell Quinton, also known as “Sky,” grew up in this rural, segregated, tight-knit community and attended a two-story school known as the Sharptown Colored Elementary School. His boyhood memories were of farm chores, school and softball games and Methodist revivals. Those childhood memories also included neighbors working together to prepare the fields for the cultivation of crops for spring planting. In the fall near Thanksgiving, families gathered together for the task of slaughtering hogs and the preservation of hams, scrapple, sausage and the remainder of the meat for the winter. Those rituals were a way of life for the Quinton family and their neighbors for more than 200 years. As a child, Newell attended the segregated Sharptown Colored Elementary School that had the traditional pot belly stove which provided uneven heat, the outside pump that provided cool water, and the outside toilets as rest rooms. His books were often outdated, tattered and torn, hand-me-downs from the students in the white schools. His memories also included chores that had to be completed prior to leaving home for school. School was not an option because his parents emphasized the importance of education. Upon graduation from Sharptown, Newell attended high school at Salisbury High School in Salisbury, Maryland, and graduated in 1962. After graduation, Newell attended Morgan State College (MSC), now Morgan State University, in Baltimore, Maryland. Salisbury High School Photo from the Baker Family papers (2012.200) Salisbury University Nabb Research Center Even though Newell and the group did not know of Rosenwald’s connect-ion to the school, Newell did know “that his grandpa and his neighbors’ grandpa-rents had built it.” Newell also found that the San Domingo community had also contributed $800 for the building of the school. Newell was also joined in the res-toration project by his wife, Tanja R. Henson-Quinton. Rudolph Stanley also pho-tographed and filmed the progress of the restoration project for posterity. That core group believed that the rural area and farming culture of San Domingo had taught them discipline, and their fight for an education taught them to value it. They also believed that the restoration and preservation of Sharptown Colored Elementary School was their effort to pass those same ideals on to the next generation and to save their history because they also believed that it was their responsibility to continue the legacy of their ancestors. Their focus on the school’s restoration was exceptionally important to them because it was their belief that their education at the school had instilled in them the idea that in order to get something one had to work for it and put time and labor into it to earn it. With Newell at the helm, the group began to study the history of the com-munity, which proved to be an arduous task because most elders of the commun-ity had died and others had no memory of the past. They turned their complete focus on the Sharptown Colored Elementary School because their families trea-sured the opportunity for their children to obtain an education, even though it was segregated, and, therefore, taught their children that if they got an educa-tion, no one could take it from them. In 2002, the group learned that the Nation-al Trust for Historical Preservation had named Rosenwald Schools to its list of most endangered places. With that knowledge and other information they had gathered, in 2004, Newell Quinton and the group officially began efforts to renovate the school to its original state. After numerous grant applications, the school was restored with about $200,000 in grants from the National Historic Trust, the Maryland Historic Trust, the Community Foundation of the Eastern Shore, and local donations. Preservation Maryland also provided $5,000 for school roof repair. The project reached fruition and on August 23, 2014 the school was dedicated as the San Domingo Community and Cultural Center In 1966, Newell graduated from Morgan with a Bachelor’s Degree in Mathematics, and he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant, and began his military service in the United States Army. He was trained as a Signal Officer and worked with computers and communications. He completed a twelve-month tour in Vietnam (September 1967 to September 1968), and received a Bronze Star for meritorious achievement. After Vietnam, Newell served as the Post Signal Officer at Fort Drum, New York, and served as a Research Analyst at Aberdeen Proving Grounds, in Aberdeen, Maryland. After nearly five years on active duty with the United States Army, he continued to serve as a member of the United States Army Reserves in various capacities for a total of 28 years of service. After five years of active duty with the Army, Newell returned to graduate school at Morgan State College (MSC) and earned a Masters of Business Administration (MBA) in 1978, with a concentration in Management. In 1971, he began his career with the Federal government as a Research Analyst at Aberdeen Proving Grounds. In 1974, he transferred to the National Institutes of Health where he worked as a Management Analyst and later as an Administrative Officer with the Department of Research Services. He later transferred to the Office of Administration, Executive Office of the President, where he was Chief of the Administrative Services Division, until 1982 when he transferred to the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). In 1982, Mr. Quinton began his career as Assistant Director of the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA) Administrative Services Staff. He was named Ad-ministrative Officer in 1985 and in 1987 became special assistant to the Deputy Chief Benefits Director for Automated Data Processing (ADP) Systems Management. He returned to the Administrative Services Staff as Director and served in that capacity from 1988 to 1989. From November of 1989 to September of 1994, he served as Director of the Baltimore Regional Office, where his concern was the overall efficiency of the programs that were formulated at headquarters and how effectively those programs served the needs of the veterans. That task involved the management of a $53 million budget and the delivery of direct services to veterans. In 1992, Newell Quinton was promoted into the Senior Executive Service, and he returned to the Veterans Affairs (VA) headquarters as Director of the Veterans Assistance Service. In 1995, Newell Quinton was named Chief Information Officer (CIO) of the Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA). There he managed a budget of approximately $120 million with a host of responsibilities, including the maintenance of the VBA information network and the telecommunications program, which provided toll free telephone service as the primary access for the nation’s veteran community. In June of 1999, he returned to the position of Director of the Baltimore Regional Office, and was responsible for the administration and delivery of veteran benefits and service for veterans and their beneficiaries who resided in Baltimore City and 21 of the 23 counties in the State of Maryland. In August of 2002, Mr. Newell Quinton retired from the Department of Veterans and returned to San Domingo and his roots on the Eastern Shore. Newell Quinton had a stellar career in the military and received numerous awards and honors. He received an award for having served as a member of the Senior Executive Service with the Department of Veterans Affairs from 1992 to 2002; in August of 2002, he received the Distinguished Career Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs; in 1996, he received the Service Award for 30 years of Service to the United States Government from the Department of Veterans Affairs; and in 1968, he was the recipient of the Bronze Star Medal. Upon his return to San Domingo, Newell built a home on land once owned by his great-grandparents. He was soon involved with a new project and profession- a preservationist. He found that there were very few reminders/memories of the local church, the Sharptown Colored Elementary School, and the tight-knit community that had sustained him in his youth and had encouraged him to succeed. Upon that realization, he enlisted the aid of his cousin, Rudolph Stanley, who taught mathematics in Salisbury, and others. They began to interview elders in the community, collect oral histories, and established a mission to preserve and protect the memories of San Domingo’s past. They also developed a plan to renovate the Sharptown Colored Elementary School where Newell obtained his early education. From their research, Newell and the core group of volunteers who joined him in the venture to renovate the school, found that the school had been built in 1919. They also discovered to their surprise that the school had been a Rosenwald School, which had been built as a partnership between Julius Rosenwald, a rich Jewish businessman and president of Sears, Roebuck and Company. Rosenwald had partnered with Booker T. Washington, the first principal and leader of Tuskegee Institute, Tuskegee, Alabama, and together they had created a program that helped to build over 5,300 schools, teachers’ quarters and other educational facilities for African Americans across 15 southern states. Even though Newell and the group did not know of Rosenwald’s connection to the school, Newell did know “that his grandpa and his neighbors’ grandparents had built it.” Newell also found that the San Domingo community had also contributed $800 for the building of the school. Newell was also joined in the restoration project by his wife, Tanja R. Henson-Quinton. Rudolph Stanley also photographed and filmed the progress of the restoration project for posterity. That core group believed that the rural area and farming culture of San Domingo had taught them discipline, and their fight for an education taught them to value it. They also believed that the restoration and preservation of Sharptown Colored Elementary School was their effort to pass those same ideals on to the next generation and to save their history because they also believed that it was their responsibility to continue the legacy of their ancestors. Their focus on the school’s restoration was exceptionally important to them because it was their belief that their education at the school had instilled in them the idea that in order to get something one had to work for it and put time and labor into it to earn it. WI-676 San Domingo School Northeast Elevation Paul Touart Photograph WI-676 Architectural Survey MD Historical Trust San Domingo School, Front Preservation Maryland 2005 WI-676 Second Floor Hall Paul Touart Photograph WI-676 Architectural Survey MD Historical Trust With Newell at the helm, the group began to study the history of the community, which proved to be an arduous task because most elders of the community had died and others had no memory of the past. They turned their complete focus on the Sharptown Colored Elementary School because their families treasured the opportunity for their children to obtain an education, even though it was segregated, and, therefore, taught their children that if they got an education, no one could take it from them. In 2002, the group learned that the National Trust for Historical Preservation had named Rosenwald Schools to its list of most endangered places. With that knowledge and other information they had gathered, in 2004, Newell Quinton and the group officially began efforts to renovate the school to its original state. After numerous grant applications, the school was restored with about $200,000 in grants from the National Historic Trust, the Maryland Historic Trust, the Community Foundation of the Eastern Shore, and local donations. Preservation Maryland also provided $5,000 for school roof repair. The project reached fruition and on August 23, 2014 the school was dedicated as the San Domingo Community and Cultural Center. Numerous volunteers also gave of their time, energy and effort to help restore the school. In the process, in 1998, the Quinton siblings established the John Quinton Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization named after their great-grandfather for the purpose of providing educational support to youth through the granting of educational scholarships, awards and tutorials to some college-bound students from San Domingo and the surrounding areas, and the gathering of oral traditions. San Domingo School Photograph by Jimmy Emerson, DVM May 11, 2016 The school has become a beacon to the community and is a testament to the hard work of Newell Quinton and the other supporters who worked on the project. The second floor of the school serves as a community meeting place and entertainment venue and is also a home to a small Masonic Lodge. The renovation is complete, but Newell Quinton is still very active in preserving other vestiges of the community because he believes that it is his responsibility to continue the legacy of his ancestors. As such, each fall near Thanksgiving, Newell, Rudolph Stanley and others gather for the daylong ritual of slaughtering hogs and the preparation of everything from the salting of hams to the making of scrapple, and sausage for the winter. The processing of the meat is a time-worn memory of years prior to integration, refrigerators and the purchasing of meat from supermarkets, or other food chains. The slaughtering of hogs and other animals as well as the raising of chickens, goats, etc., are also taught by Newell to youngsters and other interested persons in order to pass on to them the values of a community that believed in self-help, independence as well as support and cooperation with one’s neighbors, and “it takes a village to raise a child.” Newell Quinton’s goal is to preserve those memories and the culture of San Domingo, as well as the values he was taught in his youth and helped to sustain him throughout life. In order to spread the word about those values and the slaughtering of animals, he has spoken at the Ward Museum in Salisbury and various other venues. Mr. Newell Quinton is very well-known for his military career, but locally, he is also known for his outstanding community service and his desire to preserve survival skills and pride in self that were learned from his ancestors. As such, he believed that he must pass those ideals and values onto the next generation or the culture would be lost forever. For his work in the local community, he was the recipient of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Achievement Award from the Tri-County Organizations’ Coalition, Inc., in 2012. Mr. Newell Quinton is still very active in the community. He presently operates Gran’ Sarah’s Hill, a 40-acre farm with 50 goats. The farm is named after his great-grandmother Sarah, the granddaughter of the community founder James Brown. He cares for the farm because it is a labor of love. He also continues to raise and care for hogs so that he can demonstrate the manner in which his ancestors provided for their families during the winter months--survival. As Newell and others continue the ritual of slaughtering animals and teaching others, they offer the food to friends and neighbors who decide to stop by. No portion of the animal is wasted. It is that care of the animals and the land that is so near and dear to him, and that motivates him to continue to follow a way of life that help-ed the San Domingo community to survive for all of those years. As a testament to his hard work in the preservation of the culture of the community, but specifically for the renovation of the school, in 2023 the San Domingo School was selected and honored as one of two examples of Rosenwald Schools throughout the State of Maryland. Newell Emerson Quinton is truly a preserver of culture. Newell Quinton Making Scrapple

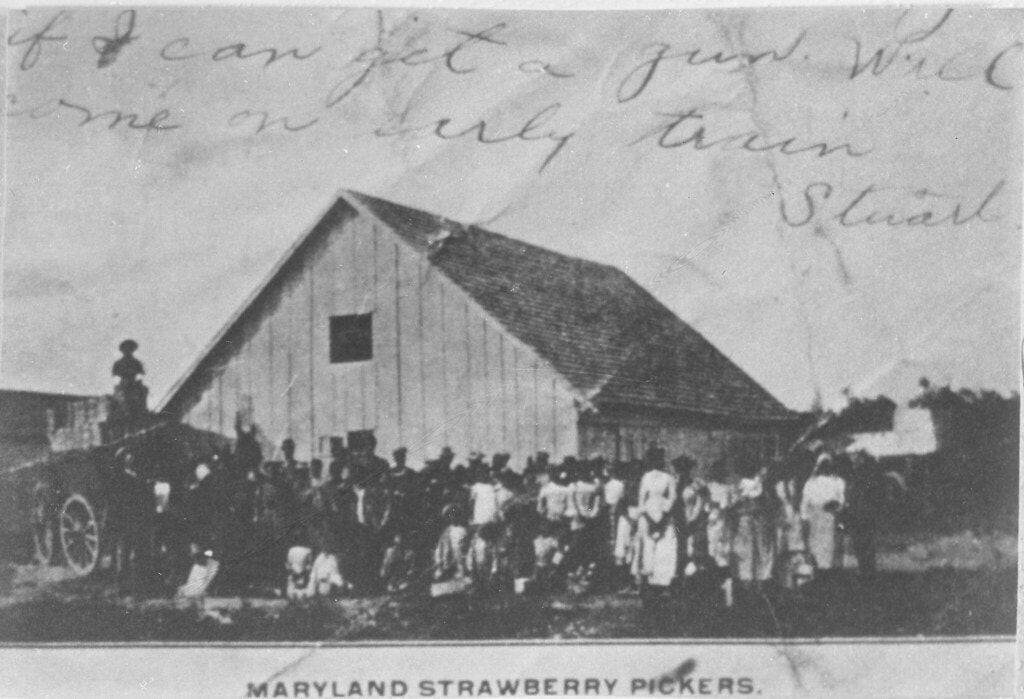

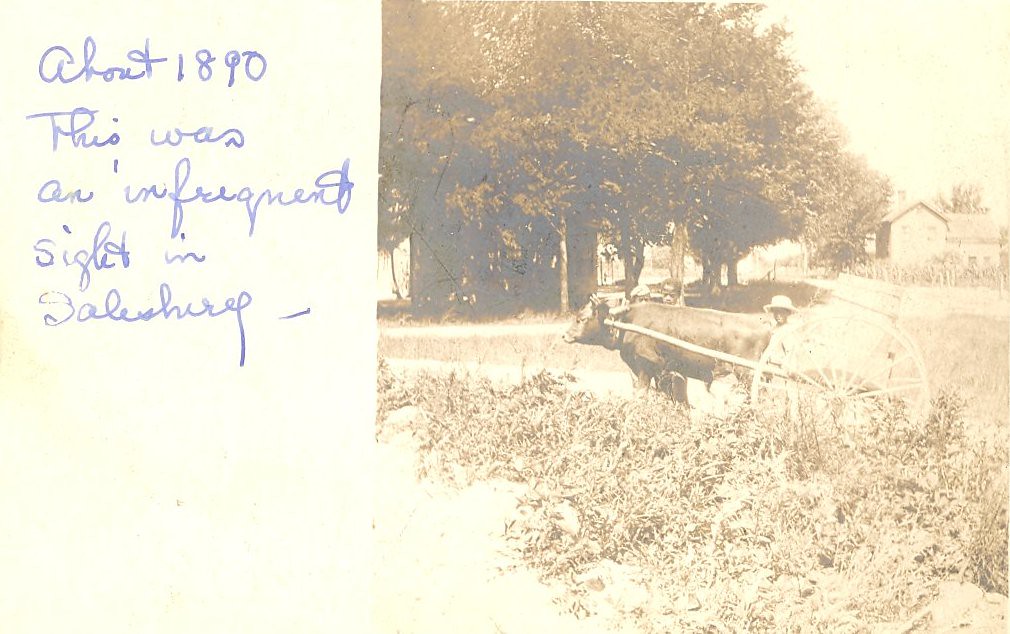

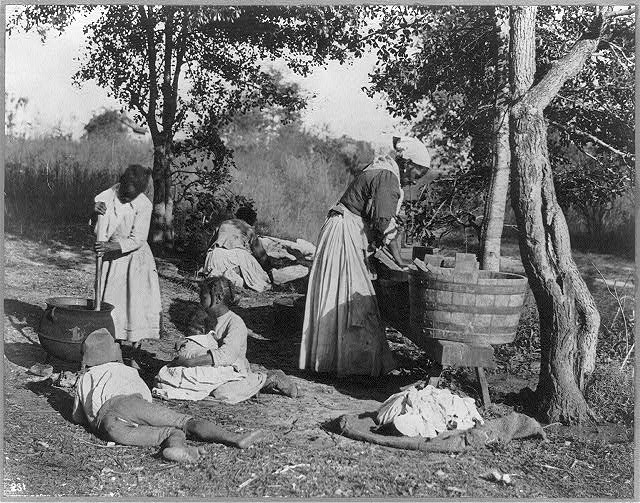

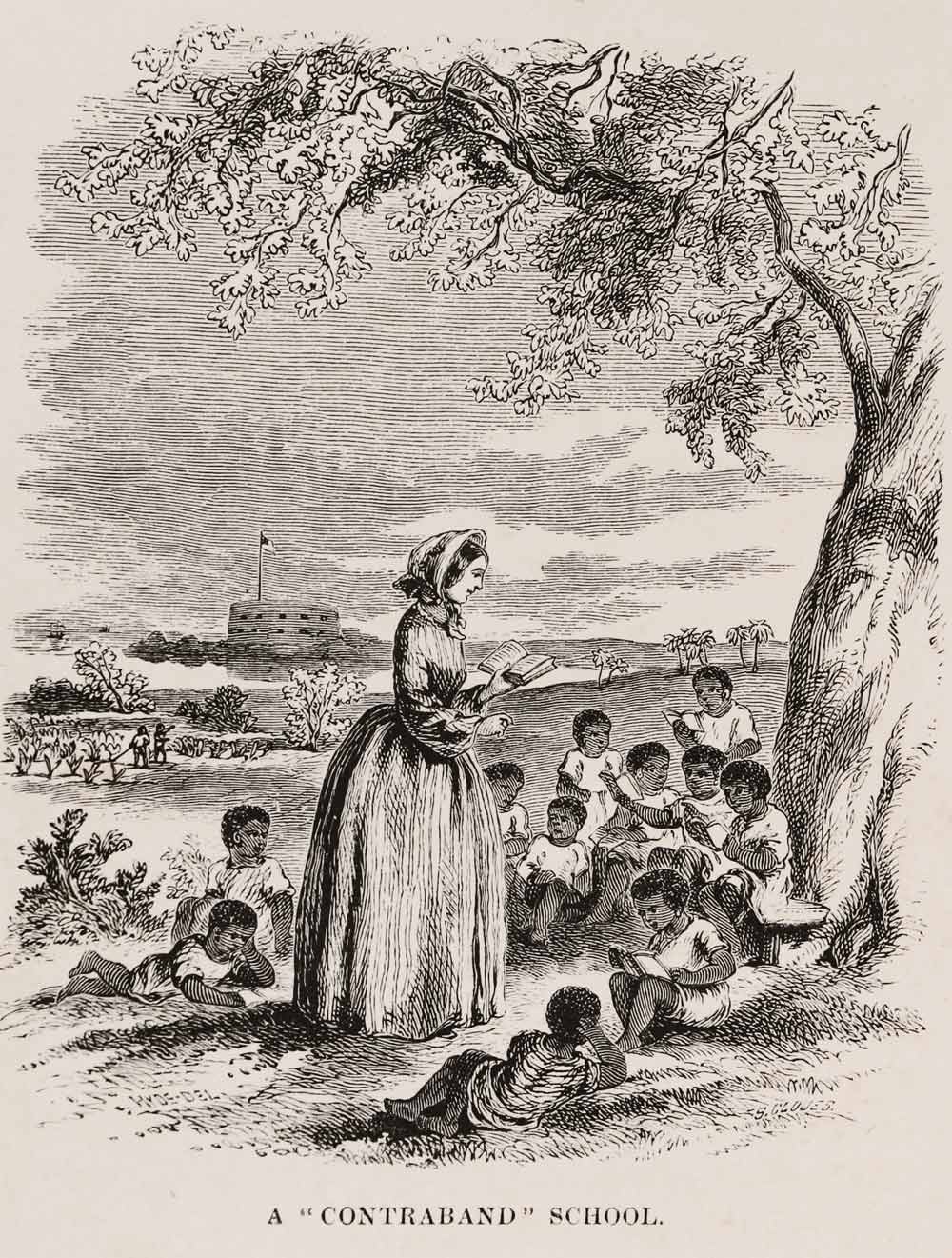

From Savoring Scrapple, Saving San Domingo Tom Horton c. 2020 Article by Andre Nieto Jaime Aerial, Parsonsburg, Maryland Walter Thurston Photograph Collection (2016.096) Nabb Research Center The small towns of Eastern Wicomico County, such as Willards and Pittsville, share much in common. They all emit a quaint, old small-town vibe and are surrounded by acres of fields that reflect the importance of agriculture in Eastern Shore culture. The history of this area also shares much in common. For instance, the introduction of the railroad in the late 19th century gave these towns promoted development by giving a boost to agricultural exports, such as strawberries. The railroad also opened the door for factories and lumber mills to thrive. However, another detail in the history of these towns that is often omitted: Black life. African Americans lived similar work lives as their white neighbors, with many being farmers themselves. Domestic services were also provided by African Americans, with many Black women serving as washer women and servants in white households. African Americans also provided labor for the emerging industries in the area, becoming factory and mill workers. Black workers contributed to the emergence of small towns in Wicomico County by working in several key areas, especially agriculture, and these contributions deserve to be highlighted in the history of the area. After the abolition of slavery, newly freed men and women were not given much to start off from. Most would have lacked an education due to restrictions placed on educating the enslaved. They also lacked generational wealth, thus having no safety net or pre-existing funds to ease their economic struggles. Racial barriers imposed by emerging Jim Crow restrictions also made employment difficult for Black Americans. The only experiences that most formerly enslaved had were farming and domestic work. Thus, following the Civil War, African American occupations tended to fall into these two fields until greater amounts of Black Americans received higher education and training in skilled labor. This is reflected by the lives of African Americans in rural Wicomico County, with most being farmers or some type of domestic worker. Farming has been a way of life on the Delmarva Peninsula for centuries, even prior to European settlement. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries agriculture remained important, with many Eastern Shore inhabitants continuing to live and work on farms. Even after the Civil War, African Americans provided much of the labor for these farms as either farm hands or working their own farms. According to a publication by the U.S. Department of Commerce from 1935, there were 21,782 Black workers in Maryland listed under the category of agriculture for their occupation. 20,956 of these workers were classified as males, making it the dominant occupation for Black male workers. Examining census data from Wicomico County reflects a similar story, with farmer or farm laborer appearing as the dominant occupation for Black males. Nathaniel Trader from Glass Hill was just one of the many Black farmers on the Shore. He first appears in the 1870 Census in the Pittsburg Election District at 17 years old living with his parents Solomon and Elizabeth Trader, both also from Glass Hill. Here, Nathaniel is listed as working on a farm, presumably his father’s farm since Solomon is listed as a farmer. It is not made apparent whether this farm is owned or rented, the label farmer (as opposed to works on farm, farm hand, or farm laborer) suggests that Solomon does not farm for a wage and instead farms to produce crops for sale, to pay rent (i.e. share cropping or tenant farming), or for subsistence. Moving forward ten years to the 1880 Census in the Parsons Election District, Nathaniel was noted as being 26. He was now also living with his wife Harriet as well as his children Elijah and Ida. Additionally, Nathaniel was now a farmer himself, but as with the 1870 Census, there is no indication about whether his farm was owned or rented. However, the 1900 Census reveals that the farm was rented. Here Nathaniel was still listed as a farmer, but he now had the help of his sons Elijah and Washington. However, things change in the 1920 Census. Nathaniel, now 69 years old, was enumerated as a farm laborer who was “working out”. Perhaps Nathaniel's age and the fact that he now only lives with his wife made it difficult for him to run a farm on his own so farming as wage laborer was more practical. Whatever the case may be, Nathaniel spent most of his life farming in rural Wicomico County until his death in 1930. Farming became the way he sustained himself and his family. Nathaniel Trader and other Black farmers were part of the farming community that helped define the Eastern Shore’s culture. Maryland Strawberry Pickers Walter Thurston Photograph Collection (2016.096) Nabb Research Center This was an Infrequent Sight in Salisbury c. 1890 John Jacob Collection Postcards Nabb Research Center Domestic service was another field of work that was common among Black workers in Wicomico. When observing statistics, Black women far outnumbered the number of Black men. In 1930, 27,142 Black women in Maryland were recorded as servants and an additional 1,243 women were listed as laundry operatives. In comparison, there were 3,934 men working as servants and only 230 men who were laundry operatives. As was the case with Black farmers, census records show that a significant number of Black women and even young children were employed as domestic servants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Mary Holloway was one such domestic worker who in 1880 at the age of fifteen was working as a servant living with the family of William and Elizabeth Adkins. There was also a young Black girl who at the age of ten, Kate Hamblin, who was living with and working as a servant for the White family of John and Hester Hamblin. It is worth noting that they share the same surname, however, whether this was just a coincidence or there is some connection is uncertain. Being ten years old, Kate is too young to have been formerly enslaved and John’s occupation in the 1860 Census of Derrickson’s Crossroads (Pittsville’s former name) was listed as a merchant, so it is unlikely he would have owned slaves anyway. Nonetheless, the formerly enslaved inheriting the surnames of their former enslavers was a common practice, as was becoming employed by them. In addition to working as servants, it was common for Black women in eastern Wicomico County to be employed as washerwomen. The 1880 Census of the Dennis District, which is the area around Powellville, contains the name of one such woman, Sally Harvy. Sally Harvy was 31 at the time and living with her husband, Harvy Henry, and their children. Meanwhile, Harvy was employed as a day laborer while their eldest son, Charly, was employed as a farm hand at the young age of twelve. Even years later this form of domestic work was common among Black women. In the 1930 Census of the Pittsburg District Marie West, age 75, and her granddaughter Roxie West, age 26, were both listed as laundresses. Further down the list there was also Emma Parker with her daughter Rosa Parker, ages 57 and 30 respectively. Countless African American women worked domestically following the end of the Civil War to help augment their family’s income and build up the generational wealth that they were denied. An African American Woman Stands with a Boy 1924 Purnell & Winder Families Photograph Collection (2018.011) Nabb Research Center African-American Woman Doing Laundry c. 1900 Library of Congress While agricultural and domestic employment was common for Black Marylanders following the Civil War, they also contributed to the local economy in other occupations, especially in the 20th century. The small towns dotted across the eastern half of Wicomico County all experienced booms due to the installation of the Wicomico Pocomoke Railroad line running from Salisbury to Ocean City. Several towns, such as Pittsville, became stops along the railroad and saw several new shops, factories, and even a hotel sprout up as a result. For example, in the early 20th century several auto dealers were built within Pittsville and with those cars comes the need for automotive maintenance. One African American resident of Pittsville found employment within this quickly growing industry as a machinist at an auto repair shop according to the 1930 Census. In addition to the auto industry, several families emerged as proprietors of canning factories. One factory was opened by Paul G. Wimbrow who owned several canneries including one in Snow Hill and another in Pittsville. Lambert J. Powell was another owner of a canning factory living in the Pittsville area and other families such as the Jones families were known to be factory owners. Census data reveals that African Americans worked in some of these canneries. Powell, for instance, had a Black man named Harry Cutler boarding with him who was recorded as a laborer at a canning factory, almost certainly Powell’s factory. Railroad Station & Cannery E.I. Brown Glass Plate Negatives collection (2001.006) Nabb Research Center The lumber industry in the area also benefited greatly from the railroad, allowing easier transportation of timber and lumber to and from sawmills. Parsonsburg’s sawmills, one of which was located directly north of the line, both saw a boom in business. In 1872, Salisbury Advertiser published an article about Parsons Switch petitioning for a post office and to have its name changed to Parsonsburg. In this same article, it is written that two million feet of lumber was purchased the year before from Parsonsburg alone by a firm located in Salisbury, demonstrating the success of Parsonsburg’s two lumber mills of the time. Pittsville, Willards, and even the crossroads town of Powellville further south all witnessed a growth in their lumber industries which translated to opportunities for Black workers. Both Samuel and George Harmon, brothers living in the Pittsville area, were able to secure work in a sawmill. However, having trees to turn into lumber requires people to fell those trees and many African Americans took up this line of work. Many of these timber cutters lived in the Dennis Election District, such as 20-year-old Lenord Coles and 58-year-old John D. Adams, just to name a few. These individuals helped fulfill the demand for lumber in the early 20th century. Powellville, MD., Mill Pond Walter Thurston Photograph Collection (2016.096) Nabb Research Center A trend can be discerned by observing the occupations of Black Wicomico residents and comparing them as time goes on. Initially, in the late 19th century one notices that children often took up the work of their parents, especially in this case where there is not much option for economic or social mobility. This can be seen with Emma Parker and her daughter Rosa working as laundresses or the countless sons like Nathaniel Trader helping their fathers on their farms and becoming farmers themselves. This mirrors the condition of Black workers across the nation following the end of the Civil War who were not given much, if anything, to start their new lives with. Increased educational opportunities afforded to their children, through the efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau and later Rosenwald Schools, helped improve economic mobility for African Americans. Black residents in Wicomico County not only helped the development of these towns, which peaked in the late 19th early 20th century, but they also helped define the culture of the Shore. Numerous Black men worked in similar industries as their white neighbors, especially agriculture, that are important staples of life here on the Lower Eastern Shore. They also found employment in emerging industries that came from the development of the railroad through the Eastern Shore, working in newly built factories, mills that witnessed a boom in business, cutting the timber that those mills required, and working on the railroad itself as was the case with William Nichols in the Parsons District. Meanwhile, Black women provided domestic services for many White families by working as not only servants, washer women, and laundresses, but also as home makers for their families. Countless women were listed as either having no occupation or listed as being at home for their occupations. This does not mean that they were idle at home, instead, they were almost certainly performing the vital and underappreciated task of maintaining the home. Black men and women contributed to the economy and society in rural Wicomico County in ways that are often overlooked while examining the history of the area and it is important to recognize their contributions to our collective history. ReferencesPrimary Sources: Entry for John S. Hamblin. United States Census, 1860, Household Identifier 2186, Line Number 33 309 Page Number 9. FamilySearch. Salt Lake City, Utah Entry for Nathaniel Trader. United States Census, 1880, Household Identifier 69, Line Number 21 Page Number 14. FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN79-KLG : Fri Mar 08 19:30:58 UTC 2024). Salt Lake City, Utah. Entry for Nathaniel Trader. United States Census, 1870, Household Identifier 94, Line Number 12 Page Number 9. FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN35-PW3 : Tue Mar 05 10:11:39 UTC 2024). Salt Lake City, Utah. Entry for Nathaniel Trader. United States Census, 1900, Household Identifier 12, Line Number 60 Page Number 1B. FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M32V-9C8 : Tue Mar 05 14:29:07 UTC 2024). Salt Lake City, Utah. Entry for Samuel Harmon and George. United States Census, 1920, Household Identifier 25, Line Number 51 Sheet Number 2B. FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M677-C3D : Sun Mar 10 16:35:58 UTC 2024). Salt Lake City, Utah. 15th Census, population, 1930. [microform]. Reel 881. Internet Archive. San Franciso, California. “Paul G. Wimbrow.” The Daily Times, May 13, 1988. 10th Census, 1880, Maryland [microform]. Reel 0517. Internet Archive. San Franciso, California. 13th Census, 1910 [microform] Population Maryland. Reel 570. Internet Archive. San Franciso, California. U.S. Department of Commerce and Bureau of the Census. Negroes in the United States: 1920-1932. Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1935. Secondary Sources:

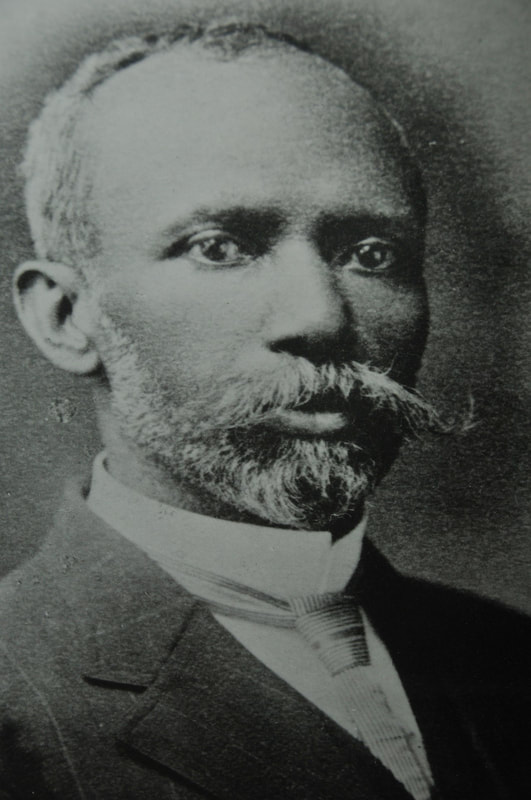

Custis, Colbi. Town of Pittsville. “History.” Last modified July 2019. https://pittsvillemd.gov/history/ Hutson, Cathy Wilkins. “Nathaniel Trader.” Find a Grave. Last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/237907825/nathaniel-trader Mandle, Jay R. Continuity and Change: The Use of Black Labor After the Civil War.” Journal of Black Studies 21, no. 4 (June 1991): 414-427. Smith, John David. “The First Friend: The Freedmen’s Bureau.” In We Ask Only for Even-Handed Justice: Black Voices from Reconstruction, 1865-1877, 38-47. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014. Vedder, Richard K. “Four Centuries of Black Economic Progress in America.” The Independent Review 26, no. 2 (Fall 2021): 287-306. WI-504 Willard Survey District Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-504, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-504.pdf WI-571 Powellville Survey District Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-571, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-571.pdf WI-489 Pittsville Historic District Architectural Survey File, 04 April 2013. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-489, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-489.pdf WI-487 Parsonsburg Survey District Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-487, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-487.pdf Article by Dr. Clara Small William C. Jason Sr. (1859-1943) William Charles Jason was born October 21, 1859 in Trappe, Maryland to William Jason, an ordained minister and Mary Wing Jason, the daughter of Charles Wing, a Methodist clergyman, of Wilmington, Delaware. William Jason’s life was governed by his Christian heritage, a quest for knowledge, and a desire to educate others. William’s early years were spent in Easton and Cambridge, Maryland. After losing his mother at an early age, Jason and his three brothers were reared by their father. By the age of fifteen, Jason was apprenticed to a printer in Easton. He also learned to be a barber and opened his own shop in Easton at age eighteen. However, he desired to obtain an education, so he sold his barbershop and went to Lima, New York to attend Genesse Wesleyan Seminary, a Methodist Episcopal Preparatory School. His tuition was paid by him operating a barbershop in that area. Through hard work and persistence, he graduated cum laude from the seminary in 1884. His quest for knowledge was incomplete, so in the fall of 1884 he enrolled in Allegheny College at Meadville, Pennsylvania. From that institution, he earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1888 and a Master of Arts in 1889. In 1891, he earned a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Drew Theological Seminary in Madison, New Jersey. After obtaining his degree from Drew Seminary, William Jason was accepted into the Delaware Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church. A few years later, Wiley University in Marshall, Texas bestowed upon him the degree of Doctor of Divinity. As a minister of the gospel, William Jason’s first charge was in Orange, New Jersey, and within four years, he had erected a church. An earlier apprenticeship as a printer in Easton, Maryland was instrumental in providing him the funds for the erection of the church. He also served as the pastor at the Tindley Temple at the Bainbridge Street Memorial Church and the Janes Church in Philadelphia. In 1896, he was released from his pastorate to become the President of Delaware State College (DSC) at Dover, now Delaware State University. The college was established on May 15, 1891, as the State College for Colored Students by the Delaware General Assembly under the provisions of the Morrill Act of 1890. That act provided for land grant colleges for Blacks in states that maintained separate educational facilities. Delaware State College opened its doors to students in 1892, and Dr. William C. Jason was elected as the second president, the first black president of the college, and the dominant personality during the first 25 years of its existence. When he took over the reins of the college, the school consisted only of the old mansion house of the Lockerman plantation and a stable which had formerly been the slave quarters. Dr. Jason assumed the task of developing “the college as an instrument for the upgrading of the Negro in Delaware.” One of his goals was to raise funds among Delaware Negroes to transform the old slave quarters into a chapel, because he wanted “to make over a place of misery and horror into a place of rejoicing.” His overall goals were to educate the youth of Delaware and for making Negro youth in Delaware aware of the opportunity for higher education; for hiring Alice Ruth Dunbar-Nelson, the wife of Paul Laurence Dunbar, the preeminent Black poet and author, to conduct the summer school for Negro teachers; for lobbying the state legislature for funding to operate Delaware State College and the summer school; and finally, for improving the quality of the faculty at the college. Dr. Jason hired the most highly trained and educated individuals to teach and educate future teachers despite the fact that he was not allocated adequate funds to accomplish the job. One of his highly respected teachers at the school, Pauline A. Young, stated that Dr. Jason was “expected to build academic and industrial agricultural curricula simultaneously without adequate funds, staff, or physical plant.” Dr. Jason served as president of the college for 28 years, from 1895 until 1923. During that period, he provided black schools in Kent and Sussex Counties with their first highly qualified teachers. In 1923, he resigned his presidency and returned to his first love, active ministry in the Delaware Conference. He offered his resignation only after he had seen the college grow to the point that he believed it could sustain itself under new leadership. Upon his return to the ministry, Dr. Jason served charges in Cheswold, Dover, Smyrna, and Milford, and in Maryland-St. Michaels, Oxford, Delmar, and the Centreville Circuit. In 1936, he returned to Delaware State College and served as Chaplain until his health began to fail and he resigned in1941, not just from being chaplain, but also from active duty in the Delaware Conference. Dr. Jason spent the latter days of his life not far from Delaware State College in a house he had built among the trees he had planted just across the bridge from the college. A week before he died, he calmly said that he “knew that his work was done.” He died July 8, 1943. Dr. William C. Jason was a beacon of light for the education of students, especially for black students throughout the state of Delaware, specifically to the lower counties of the state. In 1950, the William C. Jason Comprehensive High School was opened in Georgetown, Delaware to fill the educational vacuum for blacks in lower Delaware. It was funded through a bequest of the philanthropist, H. Fletcher Brown, who stipulated in his will that $250,000 of his estate be given to help build a Negro high school somewhere in the lower part of the state. The William C. Jason Comprehensive High School became the first African American secondary school in Sussex County. The school was a legacy to Dr. Jason’s commitment to prepare Negro youth for the future and to stress the value of strong character and morality. In June of 1967, when Delaware’s public schools were desegregated, Jason Comprehensive High School closed its doors and it later became a part of Delaware Technical and Community College. A second reminder of his legacy is that the library at Delaware State University is known as the William C. Jason Library, which also stands as a testament to his life’s work. Recently, Dr. William C. Jason was also remembered by another factor as well, Jason Beach. Jason Beach, located in Trap Pond State Park, outside of Laurel, Delaware, had been a recreational destination for the Black community in the mid-1900s and the beach was named after Dr. Jason, the longest serving president at Delaware State College, now, University. After the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, Jason Beach was no longer for segregated recreation and entertainment and it became known as Cypress Point. However, on June 21, 2022, Governor John Carey, Natural Resources Secretary Shawn Garvin, some elected officials, and some area students gathered at the site on the Juneteenth holiday and unveiled a Delaware Public Archives historical marker and declared Jason Beach a historic site and returned it to its rightful name, of Jason Beach. In remembrance of its original name, some students and others were encouraged to research and learn the many accomplishments of Dr. William C. Jason. Jason Beach Marker

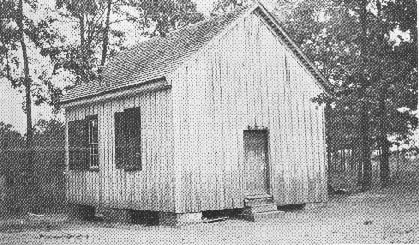

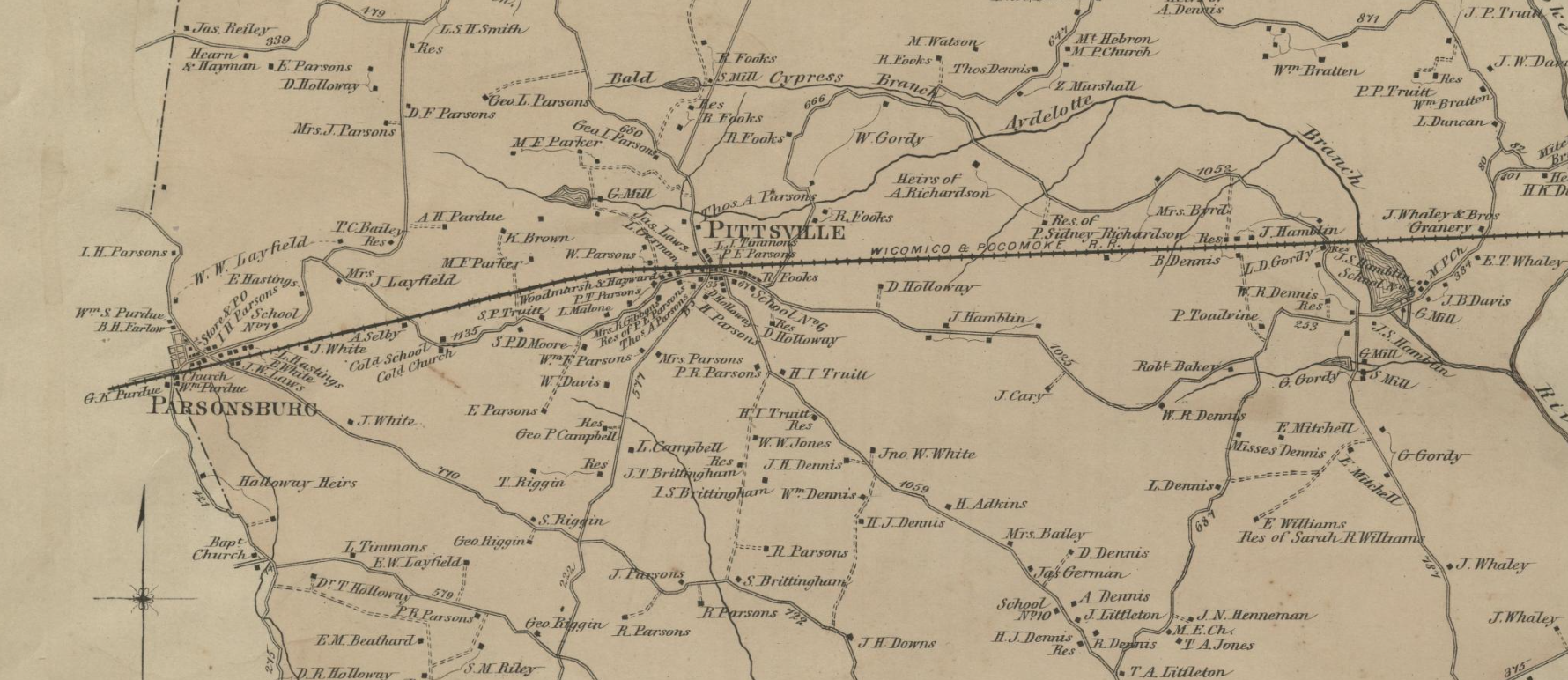

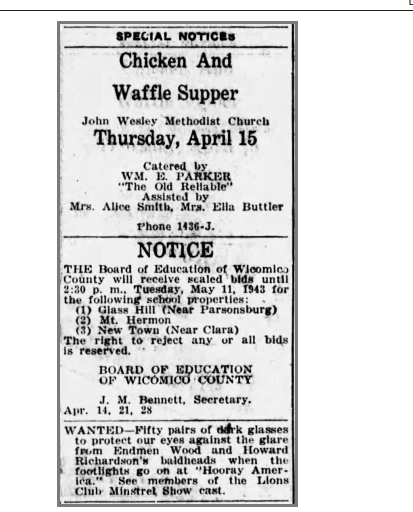

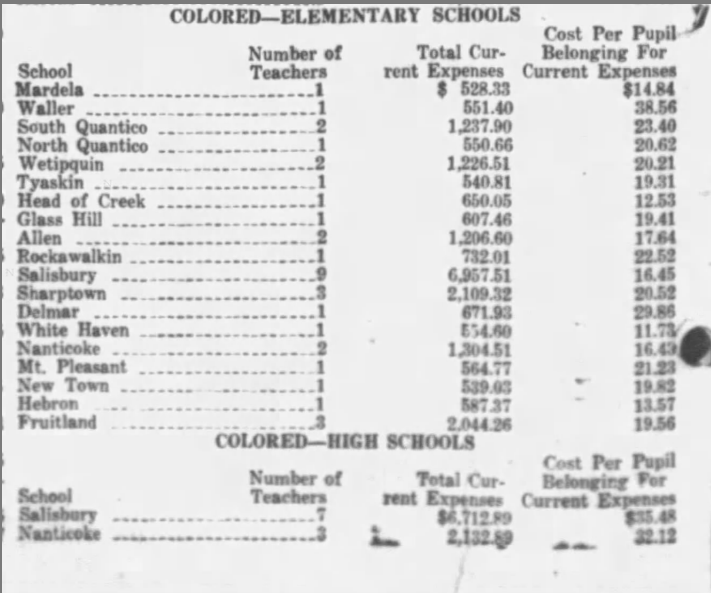

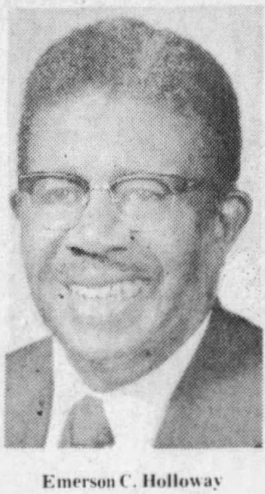

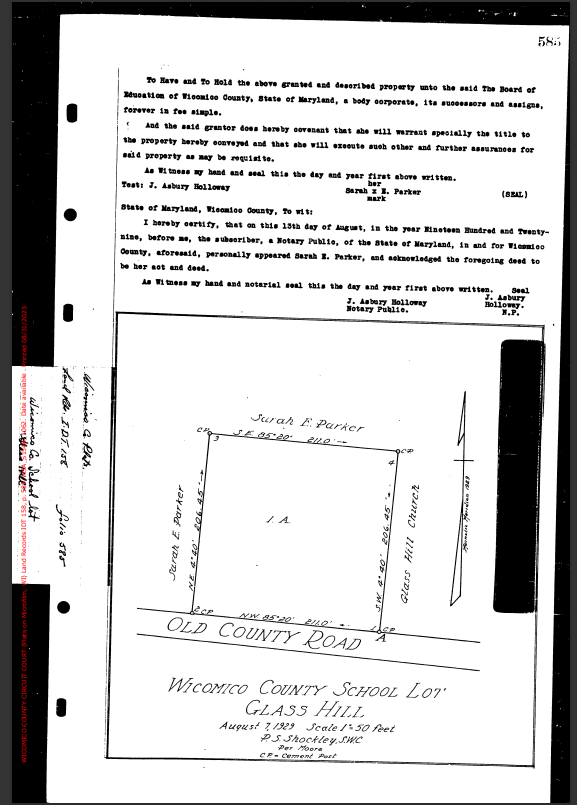

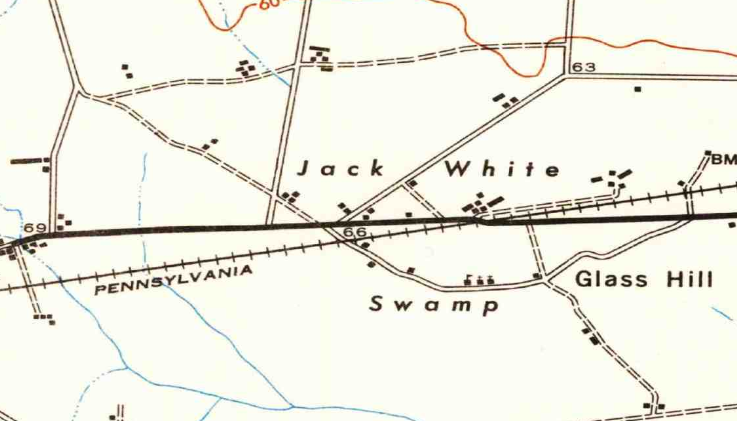

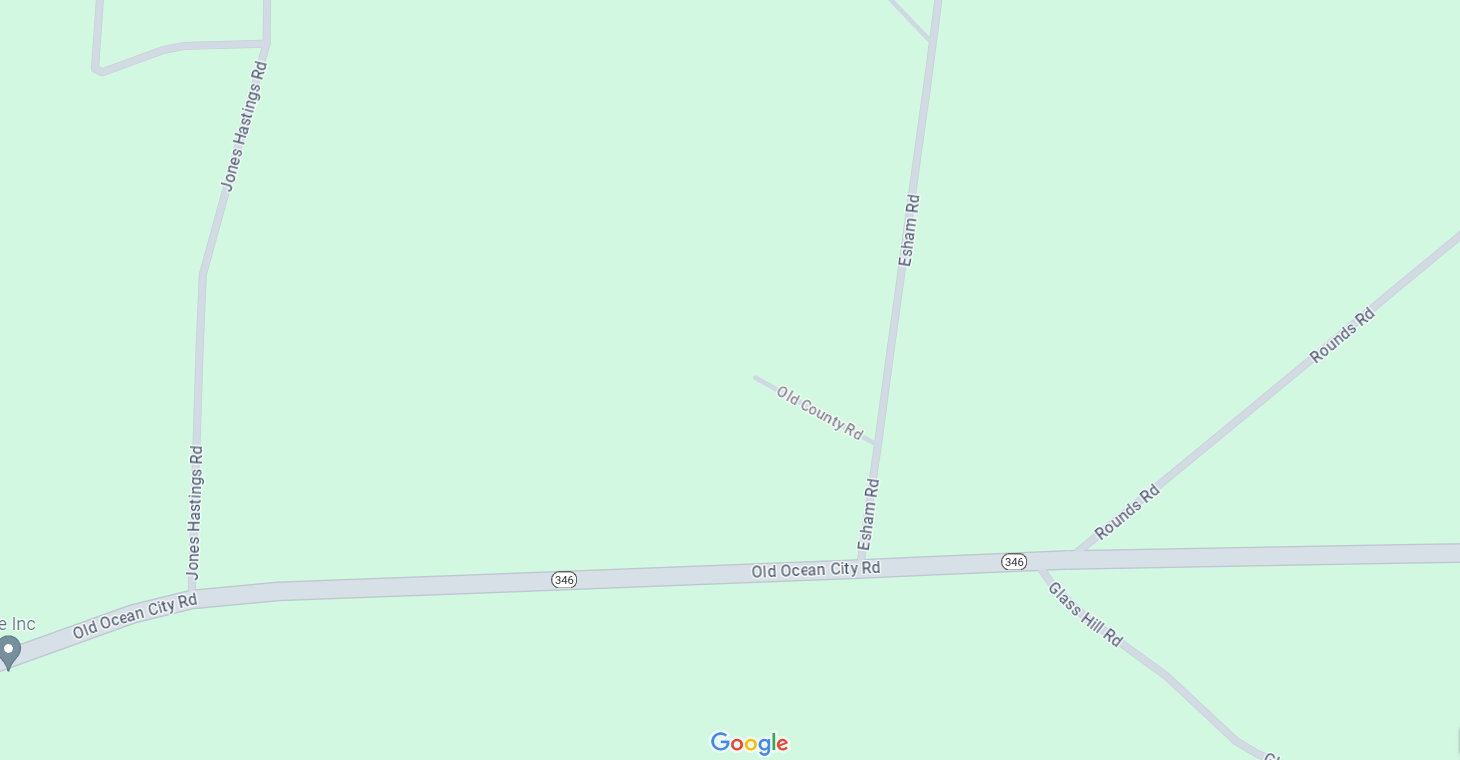

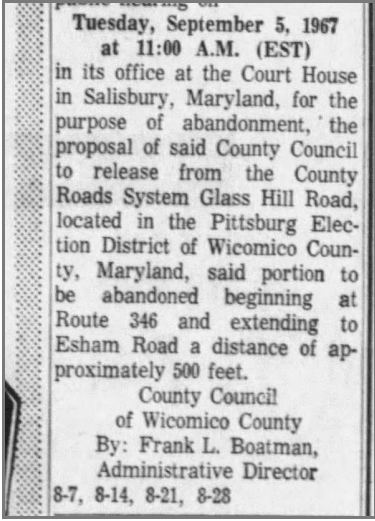

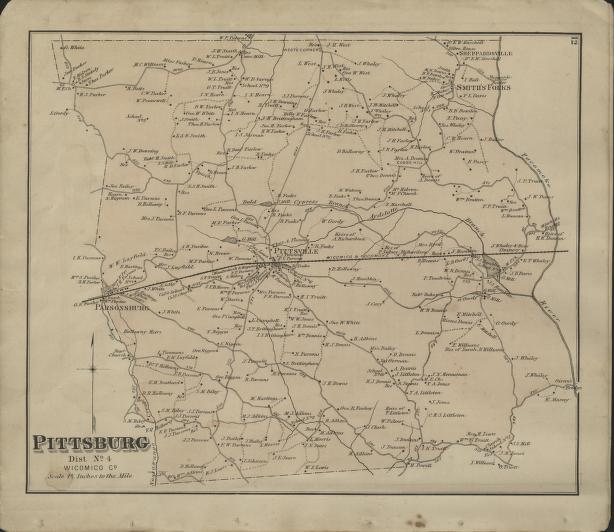

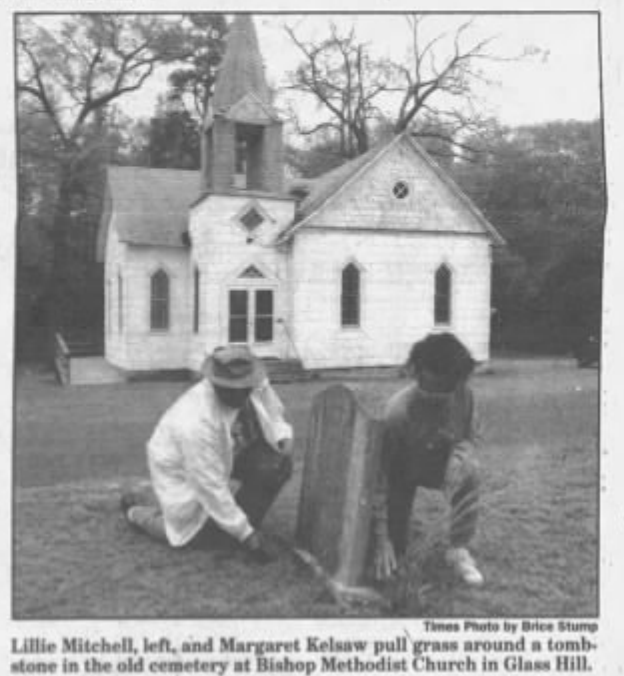

Delaware State Parks Article by Andre Nieto Jaime Glass Hill, nestled between Pittsville and Parsonsburg, was once a thriving Black community with a history that dates possibly to the late 18th century. Within this historic neighborhood once sat a one room schoolhouse, first built in the 1870s, that provided an education to the Black school children within the surrounding area. This early education was vital in the period following the abolition of slavery. At a time where opportunities for education for Black students were limited due to institutionalized biases, lack of resources, and the fact that the formerly enslaved now had to navigate their newly acquired freedom with little guidance, these early schoolhouses were crucial. These schoolhouses also had other important functions, often serving as community centers, and helped foster unity within African American communities. Glass Hill School performed its duties as an educational and community hub for at least 70 years before being closed down around the mid-20th century. Old Photograph of the Glass Hill School in Glass Hill Delmarva African American History Unknown Date Glass Hill School was just one of the many single room Black schoolhouses to crop up after the Civil War. As mentioned in the introductory article about Glass Hill, the school was built sometime in the 1870s across from the Bishop Methodist Church on Glass Hill Road. Both the church and school appeared across from each other on the 1877 Atlas of Wicomico, Somerset & Worcester Counties as “Cold [Colored] Church” and “Cold [Colored] School” in the Pittsburg District Map, confirming that the school must have been built sometime in the early 1870s. 1877 Atlas of Somerset, Wicomico, and Worcester Counties Pittsburg District Internet Archive 1877 The school appeared to have been operating well into the 20th century, with some newspapers claiming that activist Dr. Maulana Karenga (birth name Ronald Everett) attended this very school in his childhood, which would have been in the mid to late 1940s. References to the school in newspapers begin appearing consistently in the 1920s. Most of these come from The Daily Times, which published a handful of articles that mentioned Glass Hill and the school. At the time, nothing out of the ordinary would have stood out about these papers as they describe rather mundane day to day happenings and details such school reports, news, teacher rosters, and other aspects of schools. However, these old newspapers disclose several details relating to the schoolhouse. First, these papers hint at the period in which the school was active. While the 1877 Atlas has revealed that the school existed by at least 1877, the time when the school closed is a little more obscure. The Maryland Historical Trust’s inventory form WI-496 makes no mention of when the school ceased to operate. The hint provided in this document is that the building was moved to Pittsville and restored in the 1980s, meaning that the schoolhouse was in its original location for over a century. However, the school ceased its operation before this relocation and restoration. References to the school in newspapers began to decline by the 1940s. One of the last mentions of the school in its active years was an update to the roster of teachers in 1941, owing to several male teachers leaving to serve in the army. Two years later, another article stated that the Wicomico Board of Education was receiving bids for three school properties, one of which was Glass Hill. This most likely was the single room school’s lot, but it is also possible that this was a lot that was purchased by the Wicomico Board of Education in 1929. Either way, the age of the school, its one room structure, and the beginnings of integration after Brown V. Board of Education in 1954 almost certainly rendered Glass Hill School obsolete by the 1950s. By 1969, the school was being referred to as “the former Glass Hill School,” seemingly confirming its closure sometime in the 1940s or 50s. Notice Newspapers.com, The Daily Times April 14, 1943 Another element of Glass Hill, and segregated schools in general, that these newspapers reveal is how underfunded Black schools were. For example, the 1934 summary of school expenses shows that many White single teacher schools’ expenses were nearly double that of Black single teacher schools. Glass Hill’s total expenditure in this report was $607.46 while the expenses per pupil was $19.41. Meanwhile, the total expenditures of the single teacher White schools were all over $1,000 with expenses per pupil ranging from $29.49 to $54.13. Even when compared to Rosenwald Schools, which were relatively newer, but still often only had one to three teachers, had expenditures higher than these older single room schools. Sharptown School’s (San Domingo School) total expenditure was listed as $2,109.32 while South Quantico’s was $1,237.90. Yet, despite the funding disparities and older construction of the building in comparison to the other schools of Wicomico County, Glass Hill School continued providing early education for Black youth in the Pittsville-Parsonsburg area of Wicomico County well into the 20th century, a testament to the resourcefulness and strong will of the Glass Hill community. Annual Report of the Public Schools of Wicomico County Newspapers.com, The Daily Times November 20, 1934 These articles from the 20th century also reflect the impact that Glass Hill School had on an individual level. Two publications from The Daily Times described how Glass Hill School provided an education for Willie Allie Birckhead from Pittsville and another individual, Clifton Alton Trader, from Parsonsburg in their obituaries. Had the school not existed, these two students as well as the others in the area would have had to travel a much farther distance to the next closest school, likely Delmar. However, considering the distance and the fact that these children were needed nearby to work on family farms, they likely would not have received any formal education apart from any nearby tutors. W. Allie Birckhead Newspapers.com, The Daily Times November 9, 2003 Glass Hill School not only offered opportunities for local students, but to educators as well by becoming a place where several teachers started their careers. Miss Dixie Kier began teaching at Glass Hill in 1917 and taught there for three years before moving on to Delmar and Salisbury. Her career lasted 43 years, with Kier retiring in 1958 and picking up work at a Sunday and Bible school. Likewise, Emerson C. Holloway, lauded as being Wicomico County’s first male teacher, began his 37 year long career at Glass Hill School. Here, he became fondly remembered by the community, evidenced by an anecdote given by a parent, Mrs. Esther Parker Wilson. In 1939 Holloway organized a Christmas performance in which every child pitched in to create decorations or other preparations. The performance itself involved school children describing what they wanted for Christmas, singing Christmas songs, and recreating the Nativity. Wilson, among other parents, was so moved by the celebration that she said that Christmas “was never rivaled by another in that school," showing that Holloway truly had an immense impact not only on the children at Glass Hill, but the community as well. By the end of his career as an educator, Holloway had become the vice-principal at West Side Intermediate School, retiring after becoming the first Black man elected to the County Council. Thus, little Glass Hill School, provided these educators a place to gain experience and start off their lengthy careers of sharing their knowledge with countless school children across the county. Emerson C. Holloway Newspapers.com, The Daily Times November 15, 1978 This old schoolhouse also provided services to the surrounding community by serving as the Seventh Tabernacle’s early home when the congregation first came to Glass Hill. This religious organization was founded by John Elzey Parker when he came to visit his sister, Jennie Parker, in 1921. After the visit, J.E. Parker decided to settle in Glass Hill, organizing the Seventh Tabernacle, and began using Glass Hill School alongside neighboring houses to hold their meetings until they secured a more permanent location in Salisbury where they remain to this day. Even Willie Allie Birckhead, the student from Pittsville, became a member of the Seventh Tabernacle. Seventh Tabernacle on Seminole Boulevard in Salisbury Delmarva African American History c. 2011 Glass Hill School continued to serve its community well into the 20th century. However, by the early 20th century, the Rosenwald School Building Program (which was discussed more extensively in a previous StoryWay) had begun its mission of building schoolhouses for Black school children throughout the South in underserved communities. These schoolhouses were by no means state of the art, but they did help supplement and replace many of the old schoolhouses that were aged, underfunded, and falling into disrepair. They boasted a larger size and while they were still, in most cases, single roomed, they could often be partitioned into separate rooms for different grades. This allowed for increased student capacity, more teachers, and for more flexibility when it came to the usage of space. One of these schools was set to be built in Parsonsburg and was budgeted in 1929-1930 during the last big wave of school building by the Rosenwald Fund. The mention of a Rosenwald School being budgeted in 1929/1930 lines up with a transaction and land survey conducted in August of 1929, where Sarah E. Parker turned over 1 acre of land on Old County Road to the Wicomico Board of Education. This record is named “Wicomico County School Lot Glass Hill” suggesting that this lot was meant to be used for the construction of the Glass Hill Rosenwald School that was budgeted around the same time. A newspaper publication also describes this exchange, noting that the Board of Education of Wicomico obtained one acre in the Pittsburg District for the consideration of $10 from Sarah Parker. Preparations were seemingly being made to begin construction of a new school in Glass Hill, yet there are few, if any, references to a Rosenwald School in Glass Hill beyond these few documents. Wicomico County School Lot Glass Hill Wicomico County Circuit Court Plats Microfilm 1929 Today, Old County Road in Parsonsburg is a dead end and barely extends off Esham Road. However, in the past it connected to Jones Hastings Road, suggesting that a new schoolhouse may have been built somewhere on this road, but then demolished when the road was abandoned and repurposed for farmland. Looking at a map from 1950 shows Old County Road heading west and connecting to Jones Hastings Road with two structures half way down the road on its north side. To the east, the road goes through Esham Road and Route 346 (Old Ocean City Road) where it connects to Glass Hill Road on the opposite side and cuts through the railway that no longer exists. Looking at a map today (Google Maps for example) shows that the western stretch of Old County Road now terminates in trees and farmland occupies where it once was. Its eastern half section no longer connects to Glass Hill Road, simply intersecting with and ending at Esham Road now. Pittsville (1950) U.S. Geological Survey c.1950 Glass Hill Google Maps 2024 This eastern truncation can be explained by a newspaper publication from 1967 in which a public notice is given about the proposal to abandon a section of road in the Pittsburg district. This section of road is described as “beginning at Route 346 and extending to Esham Road a distance of approximately 500 feet,” which lines up with the small stretch of Old County Road that cut through Esham Road and Route 346 into Glass Hill Road. Considering this section no longer exists, it seems the proposal was accepted. At some point, the western part of Old County Road must have been abandoned in a similar manner and repurposed as farmland. Public Notice The Daily Times, Newspapers.com August 7, 1967 Another explanation for this Rosenwald School is that it never got built due to economic factors, namely the Great Depression. This economic upheaval may have gotten in the way of funding. The Rosenwald Fund found itself struggling to make payments in the 1930s and entered a decline. The State of Maryland and the Wicomico Board of Education also would have also struggled to put funding into building a new school and, like the Rosenwald Fund after 1931, likely preferred to maintain existing schools for the time being. Glass Hill residents also likely struggled to match the fund, with many leaving the area to look for employment elsewhere. A smaller community also could have meant that they did not see a need for a new Rosenwald School anymore and scrapped the idea all together. Finally, there is also the possibility that the school was built, and it just does not exist anymore. However, this seems unlikely as there are barely any references to anything other than the small schoolhouse in newspapers and documents in government databases. It is more likely that the school was simply never completed due to economic issues and the Rosenwald Fund deciding to end their school building program in 1932. Whatever the fate of this Rosenwald School was, the fact remains that the 1870s Glass Hill School managed to provide a vital education for children in the rural Parsonsburg area for around 70 years. Had the school not existed, school children would have had to travel much farther or even moved to different towns with extended family to go to the nearest African American school assuming their families could afford the loss of an extra set of hands at home. According to census records from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, many of these Black families’ occupations were farmers and homemakers; a lifestyle that relied on having every family member at home being involved in farm duties to be successful. While Glass Hill was a small school operating on a relatively small budget, it had a lasting impact on the community by giving Black school children greater access to education than their forefathers, a chance at social mobility through literacy, exposure to ideas such as equality, and by serving as a community hub alongside the Bishop Methodist Church. References: Primary: “Answer to Today’s A Moment in Time.” The Daily Times, February 9, 1998. “Annual Report of the Public Schools of Wicomico County.” The Daily Times, November 20, 1934. Atlas of Wicomico, Somerset & Worcester Cos., Md. Philadelphia: Lake, Griffing & Stevenson, 1877. “Building Shore History.” The Daily Times, March 27, 2004. “Deeds Recorded.” The Daily Times, August 16, 1929. Google. “Glass Hill.” Google Maps. Accessed January 30, 2024. https://maps.app.goo.gl/ezM7zUzBANe4J75z5. “Holloway Plans to Leave Post.” The Daily Times, November 15, 1978. “Miss Dixie Kier.” The Daily Times, July 10, 1969. “New Teachers Are Appointed for Wicomico: Two Replace Men Now Serving in the U.S. Army.” The Daily Times, August 21, 1941. “Notice.” The Daily Times, April 14, 1943. Pittsville 1950. Sheet 5960 IV NW A.M.S. Series V833 U.S. Geological Survey. U.S. Geological Survey, Washington D.C. https://ngmdb.usgs.gov/ht-bin/tv_browse.pl?id=9560f698eb5fa32f5da2a4785097ccb3 “Public Notice.” The Daily Times, August 7, 1967. "United States Census, 1880." Entry for Isaac Smith and Martha E. Smith, 1880. FamilySearch, Annapolis, MD. https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN79-GH Wicomico Co. School Lot Glass Hill. Land Records IDT 158, p. 585 MSA S1548-1062, Wicomico County Circuit Court, Salisbury, MD. https://plats.msa.maryland.gov/pages/unit.aspx?cid=WI&qualifier=S&series=1548&unit=1062&page=adv1&id=1393454667. WI-503 Calvary M. E. Church Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-503, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-503.pdf. WI-496 Glass Hill School Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-503, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-496.pdf. Secondary Sources: