|

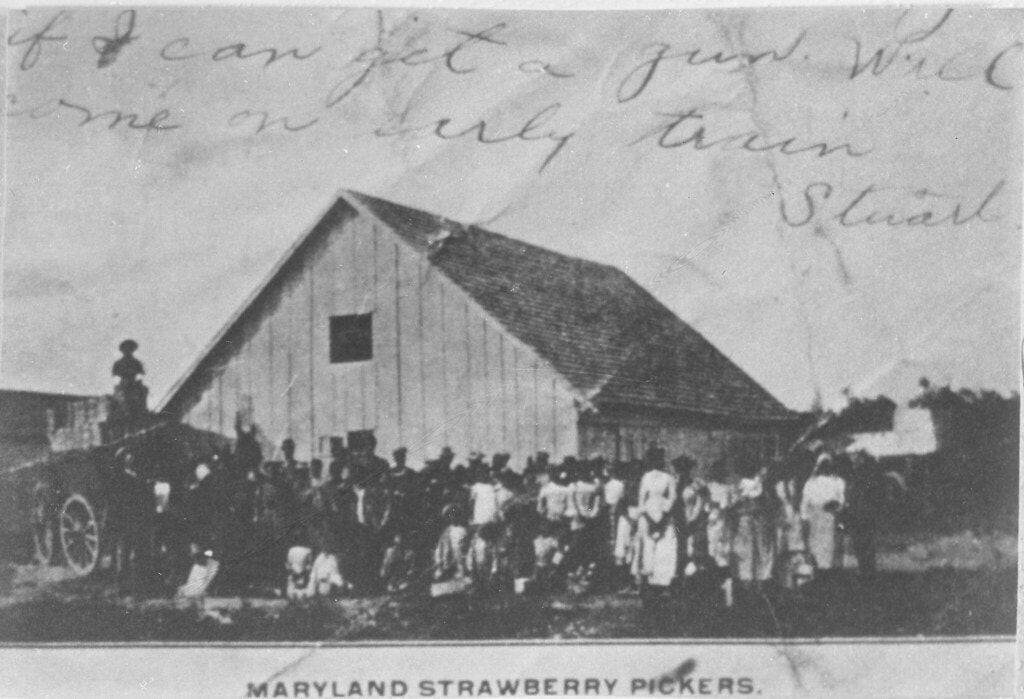

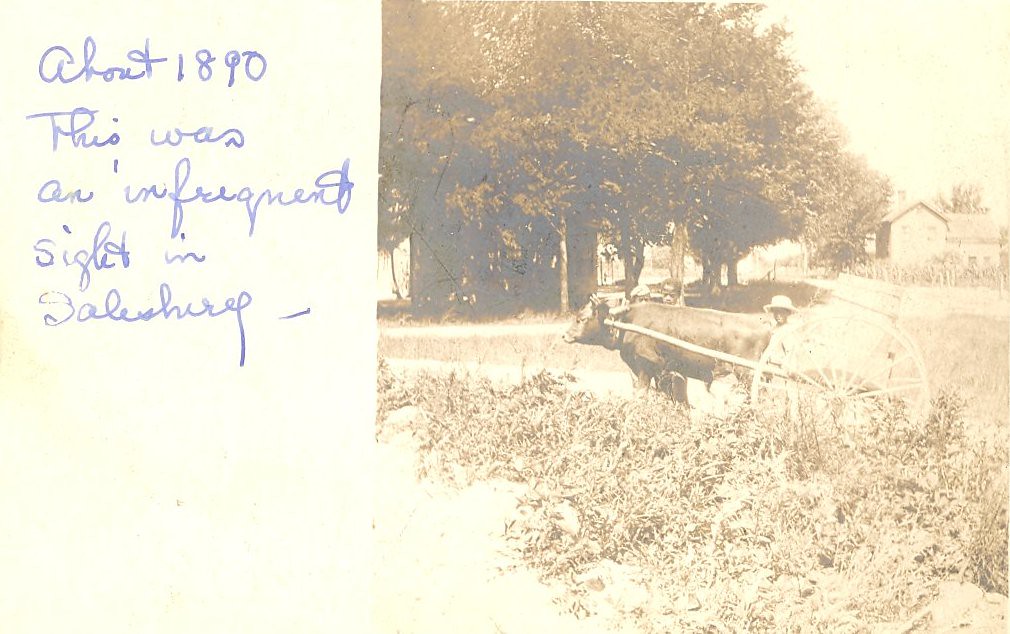

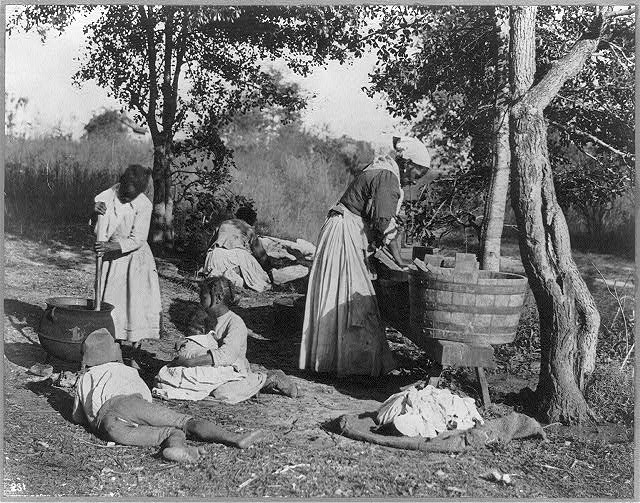

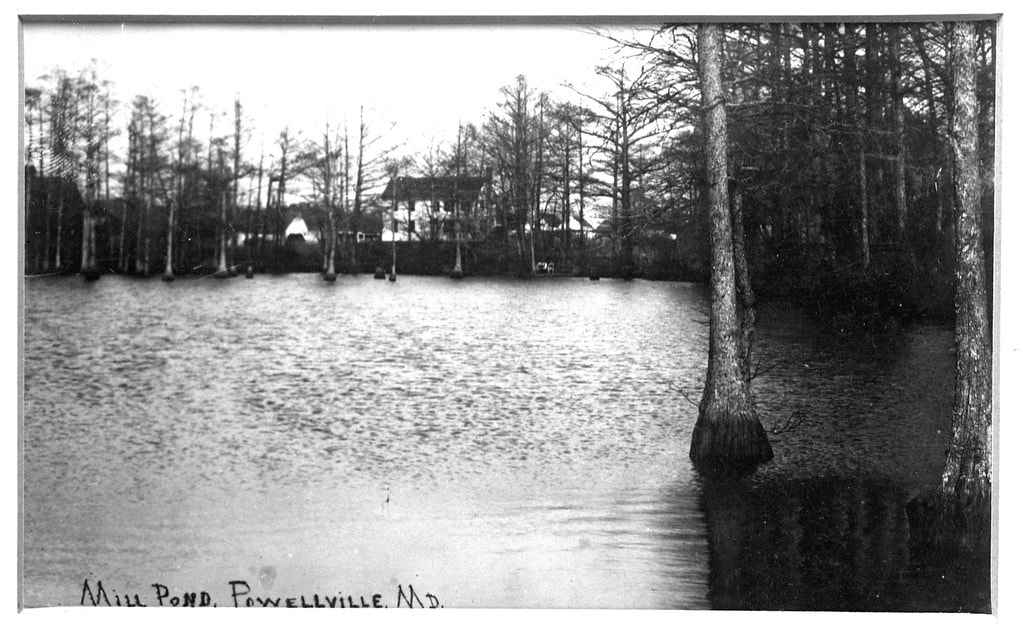

Article by Andre Nieto Jaime Aerial, Parsonsburg, Maryland Walter Thurston Photograph Collection (2016.096) Nabb Research Center The small towns of Eastern Wicomico County, such as Willards and Pittsville, share much in common. They all emit a quaint, old small-town vibe and are surrounded by acres of fields that reflect the importance of agriculture in Eastern Shore culture. The history of this area also shares much in common. For instance, the introduction of the railroad in the late 19th century gave these towns promoted development by giving a boost to agricultural exports, such as strawberries. The railroad also opened the door for factories and lumber mills to thrive. However, another detail in the history of these towns that is often omitted: Black life. African Americans lived similar work lives as their white neighbors, with many being farmers themselves. Domestic services were also provided by African Americans, with many Black women serving as washer women and servants in white households. African Americans also provided labor for the emerging industries in the area, becoming factory and mill workers. Black workers contributed to the emergence of small towns in Wicomico County by working in several key areas, especially agriculture, and these contributions deserve to be highlighted in the history of the area. After the abolition of slavery, newly freed men and women were not given much to start off from. Most would have lacked an education due to restrictions placed on educating the enslaved. They also lacked generational wealth, thus having no safety net or pre-existing funds to ease their economic struggles. Racial barriers imposed by emerging Jim Crow restrictions also made employment difficult for Black Americans. The only experiences that most formerly enslaved had were farming and domestic work. Thus, following the Civil War, African American occupations tended to fall into these two fields until greater amounts of Black Americans received higher education and training in skilled labor. This is reflected by the lives of African Americans in rural Wicomico County, with most being farmers or some type of domestic worker. Farming has been a way of life on the Delmarva Peninsula for centuries, even prior to European settlement. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries agriculture remained important, with many Eastern Shore inhabitants continuing to live and work on farms. Even after the Civil War, African Americans provided much of the labor for these farms as either farm hands or working their own farms. According to a publication by the U.S. Department of Commerce from 1935, there were 21,782 Black workers in Maryland listed under the category of agriculture for their occupation. 20,956 of these workers were classified as males, making it the dominant occupation for Black male workers. Examining census data from Wicomico County reflects a similar story, with farmer or farm laborer appearing as the dominant occupation for Black males. Nathaniel Trader from Glass Hill was just one of the many Black farmers on the Shore. He first appears in the 1870 Census in the Pittsburg Election District at 17 years old living with his parents Solomon and Elizabeth Trader, both also from Glass Hill. Here, Nathaniel is listed as working on a farm, presumably his father’s farm since Solomon is listed as a farmer. It is not made apparent whether this farm is owned or rented, the label farmer (as opposed to works on farm, farm hand, or farm laborer) suggests that Solomon does not farm for a wage and instead farms to produce crops for sale, to pay rent (i.e. share cropping or tenant farming), or for subsistence. Moving forward ten years to the 1880 Census in the Parsons Election District, Nathaniel was noted as being 26. He was now also living with his wife Harriet as well as his children Elijah and Ida. Additionally, Nathaniel was now a farmer himself, but as with the 1870 Census, there is no indication about whether his farm was owned or rented. However, the 1900 Census reveals that the farm was rented. Here Nathaniel was still listed as a farmer, but he now had the help of his sons Elijah and Washington. However, things change in the 1920 Census. Nathaniel, now 69 years old, was enumerated as a farm laborer who was “working out”. Perhaps Nathaniel's age and the fact that he now only lives with his wife made it difficult for him to run a farm on his own so farming as wage laborer was more practical. Whatever the case may be, Nathaniel spent most of his life farming in rural Wicomico County until his death in 1930. Farming became the way he sustained himself and his family. Nathaniel Trader and other Black farmers were part of the farming community that helped define the Eastern Shore’s culture. Maryland Strawberry Pickers Walter Thurston Photograph Collection (2016.096) Nabb Research Center This was an Infrequent Sight in Salisbury c. 1890 John Jacob Collection Postcards Nabb Research Center Domestic service was another field of work that was common among Black workers in Wicomico. When observing statistics, Black women far outnumbered the number of Black men. In 1930, 27,142 Black women in Maryland were recorded as servants and an additional 1,243 women were listed as laundry operatives. In comparison, there were 3,934 men working as servants and only 230 men who were laundry operatives. As was the case with Black farmers, census records show that a significant number of Black women and even young children were employed as domestic servants in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Mary Holloway was one such domestic worker who in 1880 at the age of fifteen was working as a servant living with the family of William and Elizabeth Adkins. There was also a young Black girl who at the age of ten, Kate Hamblin, who was living with and working as a servant for the White family of John and Hester Hamblin. It is worth noting that they share the same surname, however, whether this was just a coincidence or there is some connection is uncertain. Being ten years old, Kate is too young to have been formerly enslaved and John’s occupation in the 1860 Census of Derrickson’s Crossroads (Pittsville’s former name) was listed as a merchant, so it is unlikely he would have owned slaves anyway. Nonetheless, the formerly enslaved inheriting the surnames of their former enslavers was a common practice, as was becoming employed by them. In addition to working as servants, it was common for Black women in eastern Wicomico County to be employed as washerwomen. The 1880 Census of the Dennis District, which is the area around Powellville, contains the name of one such woman, Sally Harvy. Sally Harvy was 31 at the time and living with her husband, Harvy Henry, and their children. Meanwhile, Harvy was employed as a day laborer while their eldest son, Charly, was employed as a farm hand at the young age of twelve. Even years later this form of domestic work was common among Black women. In the 1930 Census of the Pittsburg District Marie West, age 75, and her granddaughter Roxie West, age 26, were both listed as laundresses. Further down the list there was also Emma Parker with her daughter Rosa Parker, ages 57 and 30 respectively. Countless African American women worked domestically following the end of the Civil War to help augment their family’s income and build up the generational wealth that they were denied. An African American Woman Stands with a Boy 1924 Purnell & Winder Families Photograph Collection (2018.011) Nabb Research Center African-American Woman Doing Laundry c. 1900 Library of Congress While agricultural and domestic employment was common for Black Marylanders following the Civil War, they also contributed to the local economy in other occupations, especially in the 20th century. The small towns dotted across the eastern half of Wicomico County all experienced booms due to the installation of the Wicomico Pocomoke Railroad line running from Salisbury to Ocean City. Several towns, such as Pittsville, became stops along the railroad and saw several new shops, factories, and even a hotel sprout up as a result. For example, in the early 20th century several auto dealers were built within Pittsville and with those cars comes the need for automotive maintenance. One African American resident of Pittsville found employment within this quickly growing industry as a machinist at an auto repair shop according to the 1930 Census. In addition to the auto industry, several families emerged as proprietors of canning factories. One factory was opened by Paul G. Wimbrow who owned several canneries including one in Snow Hill and another in Pittsville. Lambert J. Powell was another owner of a canning factory living in the Pittsville area and other families such as the Jones families were known to be factory owners. Census data reveals that African Americans worked in some of these canneries. Powell, for instance, had a Black man named Harry Cutler boarding with him who was recorded as a laborer at a canning factory, almost certainly Powell’s factory. Railroad Station & Cannery E.I. Brown Glass Plate Negatives collection (2001.006) Nabb Research Center The lumber industry in the area also benefited greatly from the railroad, allowing easier transportation of timber and lumber to and from sawmills. Parsonsburg’s sawmills, one of which was located directly north of the line, both saw a boom in business. In 1872, Salisbury Advertiser published an article about Parsons Switch petitioning for a post office and to have its name changed to Parsonsburg. In this same article, it is written that two million feet of lumber was purchased the year before from Parsonsburg alone by a firm located in Salisbury, demonstrating the success of Parsonsburg’s two lumber mills of the time. Pittsville, Willards, and even the crossroads town of Powellville further south all witnessed a growth in their lumber industries which translated to opportunities for Black workers. Both Samuel and George Harmon, brothers living in the Pittsville area, were able to secure work in a sawmill. However, having trees to turn into lumber requires people to fell those trees and many African Americans took up this line of work. Many of these timber cutters lived in the Dennis Election District, such as 20-year-old Lenord Coles and 58-year-old John D. Adams, just to name a few. These individuals helped fulfill the demand for lumber in the early 20th century. Powellville, MD., Mill Pond Walter Thurston Photograph Collection (2016.096) Nabb Research Center A trend can be discerned by observing the occupations of Black Wicomico residents and comparing them as time goes on. Initially, in the late 19th century one notices that children often took up the work of their parents, especially in this case where there is not much option for economic or social mobility. This can be seen with Emma Parker and her daughter Rosa working as laundresses or the countless sons like Nathaniel Trader helping their fathers on their farms and becoming farmers themselves. This mirrors the condition of Black workers across the nation following the end of the Civil War who were not given much, if anything, to start their new lives with. Increased educational opportunities afforded to their children, through the efforts of the Freedmen’s Bureau and later Rosenwald Schools, helped improve economic mobility for African Americans. Black residents in Wicomico County not only helped the development of these towns, which peaked in the late 19th early 20th century, but they also helped define the culture of the Shore. Numerous Black men worked in similar industries as their white neighbors, especially agriculture, that are important staples of life here on the Lower Eastern Shore. They also found employment in emerging industries that came from the development of the railroad through the Eastern Shore, working in newly built factories, mills that witnessed a boom in business, cutting the timber that those mills required, and working on the railroad itself as was the case with William Nichols in the Parsons District. Meanwhile, Black women provided domestic services for many White families by working as not only servants, washer women, and laundresses, but also as home makers for their families. Countless women were listed as either having no occupation or listed as being at home for their occupations. This does not mean that they were idle at home, instead, they were almost certainly performing the vital and underappreciated task of maintaining the home. Black men and women contributed to the economy and society in rural Wicomico County in ways that are often overlooked while examining the history of the area and it is important to recognize their contributions to our collective history. ReferencesPrimary Sources: Entry for John S. Hamblin. United States Census, 1860, Household Identifier 2186, Line Number 33 309 Page Number 9. FamilySearch. Salt Lake City, Utah Entry for Nathaniel Trader. United States Census, 1880, Household Identifier 69, Line Number 21 Page Number 14. FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN79-KLG : Fri Mar 08 19:30:58 UTC 2024). Salt Lake City, Utah. Entry for Nathaniel Trader. United States Census, 1870, Household Identifier 94, Line Number 12 Page Number 9. FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MN35-PW3 : Tue Mar 05 10:11:39 UTC 2024). Salt Lake City, Utah. Entry for Nathaniel Trader. United States Census, 1900, Household Identifier 12, Line Number 60 Page Number 1B. FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M32V-9C8 : Tue Mar 05 14:29:07 UTC 2024). Salt Lake City, Utah. Entry for Samuel Harmon and George. United States Census, 1920, Household Identifier 25, Line Number 51 Sheet Number 2B. FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M677-C3D : Sun Mar 10 16:35:58 UTC 2024). Salt Lake City, Utah. 15th Census, population, 1930. [microform]. Reel 881. Internet Archive. San Franciso, California. “Paul G. Wimbrow.” The Daily Times, May 13, 1988. 10th Census, 1880, Maryland [microform]. Reel 0517. Internet Archive. San Franciso, California. 13th Census, 1910 [microform] Population Maryland. Reel 570. Internet Archive. San Franciso, California. U.S. Department of Commerce and Bureau of the Census. Negroes in the United States: 1920-1932. Washington D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1935. Secondary Sources:

Custis, Colbi. Town of Pittsville. “History.” Last modified July 2019. https://pittsvillemd.gov/history/ Hutson, Cathy Wilkins. “Nathaniel Trader.” Find a Grave. Last modified March 24, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/237907825/nathaniel-trader Mandle, Jay R. Continuity and Change: The Use of Black Labor After the Civil War.” Journal of Black Studies 21, no. 4 (June 1991): 414-427. Smith, John David. “The First Friend: The Freedmen’s Bureau.” In We Ask Only for Even-Handed Justice: Black Voices from Reconstruction, 1865-1877, 38-47. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014. Vedder, Richard K. “Four Centuries of Black Economic Progress in America.” The Independent Review 26, no. 2 (Fall 2021): 287-306. WI-504 Willard Survey District Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-504, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-504.pdf WI-571 Powellville Survey District Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-571, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-571.pdf WI-489 Pittsville Historic District Architectural Survey File, 04 April 2013. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-489, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-489.pdf WI-487 Parsonsburg Survey District Architectural Survey File, 29 August 2003. Maryland Historical Trust Maryland Inventory of Historic Property Form Inventory No. WI-487, Maryland Historical Trust, Crownsville, MD. https://apps.mht.maryland.gov/medusa/PDF/Wicomico/WI-487.pdf

1 Comment

|

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed