|

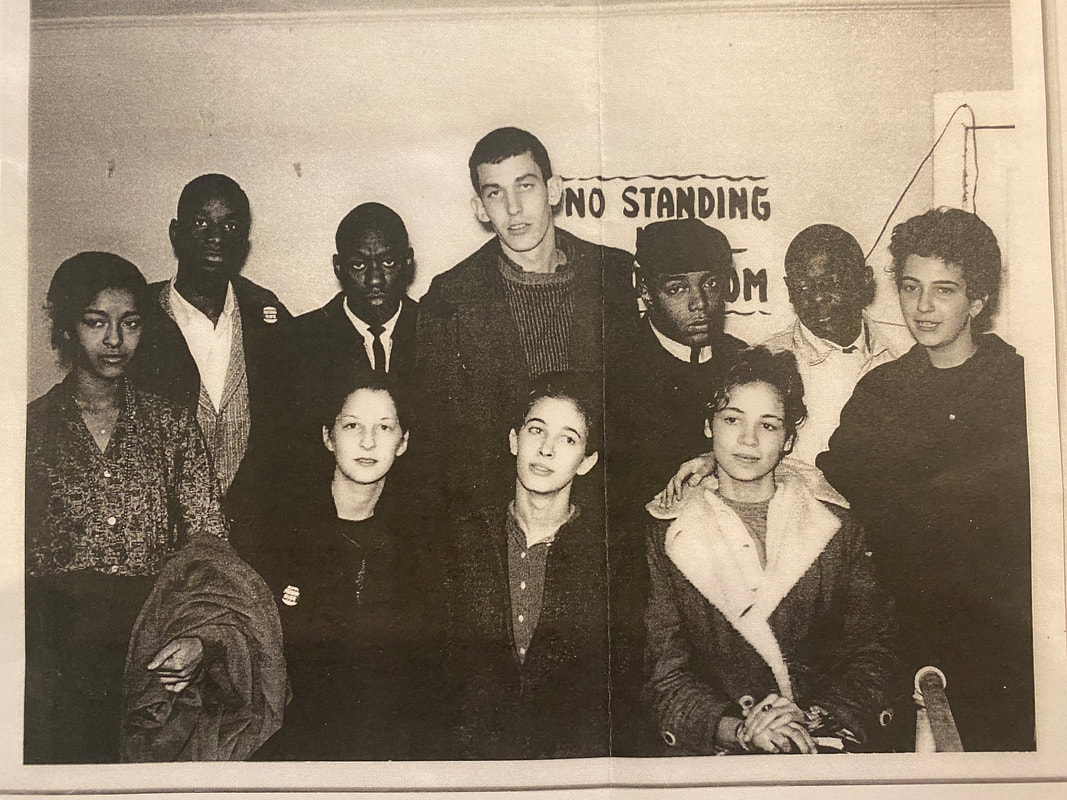

Any discussion of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s immediately brings to mind images of powerful water hoses turned on demonstrators, police dogs yelping at the flesh of protestors, condiments poured on the heads and clothing of protestors at lunch counter sit-ins, and other indecencies throughout the Deep South. Those things occurred and more, including violent beatings and some deaths, but most individuals do not associate those factors with the small fishing village of Crisfield, on the Eastern Shore of Maryland; however, reality is something quite different. On Christmas Eve, 1961, a group of protestors, mostly college students, arrived in Crisfield to stage a demonstration against racial inequality. The pro-testors were: Angeline (Angela) Butler, from New York City, aged 20; William (Bill) Hansen, Jr., from Cincinnati, Ohio, aged 21; Reggie Robins, from Baltimore, Mary-land, aged 22; Faith Holsaert, from Brooklyn, New York, aged 18; Bonnie Kilston, from New York City, aged 21; Diane Ostrosky (Ostrowski), from Baltimore, Mary-land, aged 18; Margaret (Peggie) Dammond, from New York City, aged 19; Donnie Fleming, from Baltimore, Maryland, aged 18; Frank McDougald, from Baltimore, Maryland, aged 19; and David Williams, from Baltimore, Maryland, aged 20. The group consisted of six blacks and four whites; five females and five males; and three white females, two black females, and four black males and one white male. The ten protestors and some of their relatives, some who served as look-outs, and their supporters, arrived in Crisfield, late Christmas Eve, 1961. The pro-testors were members of the Civic Interest Group (CIG), of Baltimore, Maryland and purposely chosen to protest in Crisfield, the home of then Maryland Gover-nor Millard Tawes, where public facilities were segregated. The protestors were familiar with African diplomats who had regularly traveled from New York to Washington, D.C., who in September of 1960 had been refused service at a White Tower restaurant on U.S. Route 40. As a result of that insulting situation, Presi-dent John F. Kennedy personally appealed to Governor Tawes to correct the racial incident. The President passed a public accommodations bill that related to a small area parallel to U.S. 40, but it did not extend to the rest of the state or nation. The CIG, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), had been staging demonstrations against segregation throughout Maryland to make the public aware of racial inequality and to awaken their conscience since the African dip- lomatic incident. Their goal and that of the student protestors was to obtain the support of the Governor and the Maryland General Assembly to help eliminate racial segregation by passing a public accommodations bill. The protestors arrived in Crisfield late in the afternoon. Their slogan for their planned sit-in was “No Room at The Inn,” reminiscent of Mary and Joseph in the Bible who had been refused room at the inn prior to the birth of Jesus, two thousand years earlier. The protestors arrived too late to stage the demonstration in front of the Governor’s home, but held a sit-in at a local restaurant. Unbe-known to them, the Governor had already left his home and had returned to Annapolis prior to their arrival in Crisfield. They stopped at City Restaurant, the only one that was open at the time, which was owned by Hilda Carey Marshall. When they arrived, the restaurant was closing for the evening and all of the workers had left to be with their families for Christmas Eve. The owner offered to feed the demonstrators at her home, if they were hungry, but they refused to leave the establishment, so the police were called. The demonstrators were charged with trespassing, were arrested, and jailed in Princess Anne, Maryland. When word spread about their arrest, some students from Maryland State College, now the University of Maryland Eastern Shore (UMES), serenaded them with Christmas carols. After their arrest, each protestor chose to remain in jail rather than pay $103.60 bond. On Tuesday, December 26, after a preliminary hearing, four of the protestors were released on $100 bond and the remaining six remained in jail. Those released on bail were Bonnie Kilston, Frank McDougald, Donnie Fleming and Reginald Robinson, all from Baltimore, Maryland. The bail bondsman for the four was Frederick St. Clair of Cambridge, through whom their bonds were paid by the NAACP. St. Clair was a cousin of Gloria Richardson, who later became the leader of the Cambridge Non-Violent Action Committee (CNAC), who organized sit-ins at movie theaters, restaurants and other segregated public places; regis-tered new black voters, and lobbied for equality in education, health care, hou-sing and wages. St. Clair and Gloria Richardson were also cousins of Anthony E. Ward, a local mortician who became the first Black City Councilman in Crisfield. At the preliminary hearing, the protestors asked for a jury trial. Their attorneys, Mrs. Juanita Jackson Mitchell and Paul J. Cockrell, asked that the charges be dismissed on the grounds that they were based on prejudice and a violation of the protestors’ Fourteenth Amendment rights. Their motion was denied by Trial Magistrate Albert C. Rich. Those six who remained in jail began a hunger strike and sang songs to encourage themselves in order to keep their spirits up, while imprisoned in an unfamiliar place. State and local newspapers reported that the Christmas Eve sit-in was a forerunner of an anti-segregation drive planned for the Eastern Shore, in January of 1962, which was slated for U.S. Route 50, all the way to Ocean City. In carrying out their plans, the CIG notified Governor Tawes that it planned another protest in Crisfield on Friday, December 29th, and asked the Governor to assist them in desegregating Crisfield. CORE also said that it would follow with a similar free-dom ride on Saturday, December 30th. The Friday sit-in was scheduled to coincide with the release of the six protestors who remained in jail and then they were scheduled to attend a rally at Shiloh Methodist Church, in Crisfield, where 300 persons were expected. As time wore on and the protestors remained in jail, rumors and false information were spread. One rumor was that the protestors were paid $200 each to participate in the sit-ins. Another falsehood was that 50 carloads of protestors were scheduled to descend on Crisfield. The reality was that only 50 protestors were scheduled to attend the demonstration in Crisfield on Friday, December 29th. On Friday, December 29th, a total of 120 individuals, most of them local Blacks, marched and chanted without violence. Due to bus trouble and having gotten lost about three times, the bus of 50 protestors arrived with only 28 protestors, around 8 p.m., more than five hours late. By the time they arrived, nearly all of the town’s restaurants had closed. Upon their arrival in Crisfield, two groups entered lunch counters and were served. One establishment announced that it was serving Negroes that night only, rather than changing its segregation policy. Two of the local restaurant owners agreed to allow anyone to be served in their establishments as long as they exhibited good behavior. The only arrests that were made came from two spectators for trying to annoy the protest mar-ches. Some bystanders threw eggs, but they did not reach the marchers. To the credit of everyone involved, the protests were non-violent and no one was physically assaulted. After the march, the groups went to Shiloh Methodist Church for a rally where speakers urged the passage of a public accommodations bill to end further demonstrations. The purpose of the church rally was to encourage locals to fight segregation because they would have to continue to fight in order to achieve equity once the protestors left the area. More rumors and innuendos spread throughout the local area and the state regarding the protests. For example, a statement was issued by Somerset County State’s Attorney Wade Ward, “that community leaders planned to appoint com-mittees comprised of both races and merchants to work out an agreement that would be satisfactory to all persons.” After the protestors left town on Friday, December 29, it was reported that Wade had an agreement from four Crisfield restaurants to desegregate before the freedom riders left Baltimore, but when they found that a bus load of riders were coming anyway, they tore up the agreement. Wade also reportedly revealed that CORE and CIG leaders were informed of the agreement. The bus came anyway with instructions that if they had actually agreed to integrate there wouldn’t be a demonstration. However, the bus got lost and two restaurants remained open two hours later than their normal operating hours, as a show of good faith. However, the restaurants closed before the bus finally arrived at 8 p.m. The most positive thing to come out of the protests was that the Maryland Bi-Racial Commission agreed to create bi-racial commissions on the Eastern Shore. After December 29th, protests were planned in other towns on the Shore, such as in Cambridge and Easton. For Crisfield, change occurred slowly, and without violence, as had been exhibited throughout the state and other areas of the Deep South. After restaurants opened their doors to all people, other estab-lishments followed suit. For nearly forty-three years, very little was mentioned or known about the Crisfield Protests of 1961, because most of those who witnessed the protests or participated in them had passed. For some unknown reason, pictures of the pro-testors were found in California and someone noticed that one of the pictures had a sign with the name Crisfield, Maryland on it. Those who held the pictures notified the local authorities and the Tawes Museum and inquired if they were in-terested in the photographs. The photos were sent to the museum and fortune-ately, Tim Howard, a History graduate student at Salisbury University and em-ployee at the museum, saw the photos and purchased some of them. While Howard was enrolled in Dr. Clara L. Small’s History 590 class in Local History at Salisbury University in the spring of 2004, Congressman John Lewis was a speaker in Salisbury University’s Sarbanes Lecture Series. On March 29th, 2004, students in Dr. Small’s class were given the opportunity to meet, privately for about an hour, with Congressman Lewis. Tim Howard was one of the honored students. He had some of the photographs of the participants of the Crisfield protests and showed them to Congressman Lewis. The Congressman readily identified four of the ten demonstrators in the Crisfield protests because he had participated with them in various protests, or he had trained with them in previous non-violent procedures. Recent publications of women in the Civil Rights Movement, the persistence and fortitude of Tim Howard, and those photographs will forever link the late Congressman John Lewis, one of the most famous icons of the Civil Rights Movement, to the Sarbanes Lecture Series, Salisbury University, and the little known Crisfield Protests of December 1961. Clara L. Small, Ph.D. Emerita Professor of History Salisbury University Salisbury, Maryland May, 25, 2022

1 Comment

4/30/2024 09:23:38 am

I came across this article while researching the Civil Rights movement on the Easter Shore. A place we called 'Maryland's Mississippi.' in that period. I was there but not allowed to sit in because I was only 15. The first time I got arrested was in Cambridge in 1962. I knew a number of the people in this photograph. You have my email here, I would love to be in communication with you about this era.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed